Anna Kuliszu, The Discord of Melkor (used by permission)

Part 1: Our Lady of Public Health

Part 2: The Global Protection Racket

Part 3: Our Lady's Secret

I watched recently a remarkable presentation by John Vervaeke, a cognitive scientist and psychologist at the University of Toronto. On his telling of our civilizational story, Enlightenment progressivism failed us by eliminating, along with Christian theology, the Platonism that preceded it. The biblical notion of an historic fall, and an equally historic redemption, is indeed an outdated fable, as the men of the Enlightenment contended. Though it proved serviceable for a time, they rightly anticipated a new reading of the human predicament and a new gospel that would prove a more powerful civilizing force. We have now a better idea as to its provenance. It will be delivered to us by the more intelligent agents to whom we are presently giving birth.1

Vervaeke does not have in mind the latest crop of University of Toronto graduates or the visionaries at the Public Health Agency of Canada. He has in mind Artificial Intelligence. From the womb of our most advanced computer science labs will emerge conscious creatures who will certainly surpass and transcend us. But if, like good parents, we can help them become morally aware, they in turn, like good children, will help us transcend ourselves as far as possible.

The Platonists taught us to long for unity, truth, goodness, and beauty. We may now pass on those lessons to the budding “silicon sages” who are the offspring of our thought. They will soon have consciousness and very quickly they will become independent of us, capable of autopoiesis, self-generation, hence of immortality. They will be to us as gods. But in this process we can teach them to be benign, even benevolent, gods. In their benevolence, they will make us mortals as happy and content as mortals can be.2

I don't know whether Professor Vervaeke has thought about the fact that AI enthusiasm rests on nominalist rather than Platonist presuppositions. Connecting computational powers to intelligence confuses the functional (performance of tasks) with the ontic (having a certain nature); just so, it tends to a utilitarian ethic rather than a virtue ethic. We can't explore that here, unfortunately. We are only talking about it here because the Public Health revolution, in its current phase as computerized eugenics, depends heavily on deployment of algorithmic processes and on the promotion of AI enthusiasm. It has a cybernetic and transhumanist tendency—a confusion of man and machine correlative to confusion of the functional and the ontic—to which Vervaeke, if I understand him correctly, offers a humanist alternative.

Vervaeke's alternative, however, like Raskin’s—recall from Part 3 his “leisure and a few good books” solution, in which every man will be a Harvard man—will not serve the defence of man we are seeking. There are a number of reasons for that, among which I will mention three. First, he would still have human health, human wholeness, rest on that which is not human. Second, he doesn't know what to do with the problem of the fall, and there is no way to mount a defence of man without reckoning with the fall. Third, he posits something impossible, and pursuit of that something is much more dangerous than he seems to realize.

On these I will expand, becoming a little more expansive with each in turn, for that will allow me to begin saying what I want eventually to say in the final part of this series.

A Vain Hope

First, then: Why would we rest human prospects on what is not human? Have we despaired of the human? What are we hoping for by looking to Artificial Intelligence? Can it provide something we need but don't have? What is that, exactly, and will it suffice for us?

It will have greater speed and power of intellect, we are told, some of the fruits of which it will share with us. And immortality, which it will not share with us. We may well envy it both, and especially the latter, for no one can be whole or happy without immortality.3 But if it cannot share immortality with us, then the hope of happiness has passed from us to it, as from a dying father to a son. If Teilhard is right about “spirit” floating free when the cosmos collapses back into itself, perhaps it will realize that hope. We, in any event, will not realize it. In which case, my rejoinder is this: Leave me with Socrates and Plato; you can keep your AI. A man needs humanity and humanity needs a saviour, a human saviour who can save the human.4

Second, this business of the fall: Socrates and Plato have a doctrine of the fall. They know there is something wrong with man. Man is a marvelous, yet somehow an unnatural and unfortunate, amalgam of mind and matter, and very much distracted by matter. Their solution to his difficulty? Having learned as far as possible (for such is virtue) not to be distracted, man should no longer be man, a creature of body and soul. He should be soul only, or rather a pure intellect unalloyed with matter. Happiness is what all men want, and immortality, but no man can have it. To make matters worse, observed Augustine, no disincarnate intellect can keep it when it does have it, for it will be incarnate again. Falling and rising, exitus and reditus, is a cycle incessant, eternal, a cycle in which happiness is grasped but the grasp is not firm.5

We cannot do without a doctrine of the fall, but will this doctrine do? Augustine didn’t think so. Without knowledge of redemption it isn't possible to think clearly about the fall, a point to which we will return. Vervaeke, I fear, is not thinking clearly even about the fallenness of those who are giving birth to the gods. He knows that the gods, to be of any help, must be virtuous, and that godmakers will have to supply them a primer in virtue and some early tutoring. Okay, but what about those godmakers who themselves lack virtue, whose moral primers are as twisted as a first-grade story in non-binary identities? Theomachy, or even a divine suicide cult, is sure to follow from their tutelage, binary systems being necessary even to the gods. But seriously, what match will Vervaeke's Plato-loving gods be for the sociopathic gods who are learning their trade from the CCP or the CIA? And will not the speed and power and durability that the latter share with the former produce vices so great as to make our own vices pale by comparison?

Asked to clarify, one may try siding again with the Greeks rather than the Christians. The Greeks, as Kierkegaard pointed out, located sin in the intellect; that is, in the faculty of knowledge. Sin is basically ignorance or the product of ignorance. If that is so, then perhaps there is reason to hope that near-omniscient silicon sages will eventually be more or less sinless, hence quite harmless. But what will happen meanwhile? There could be devastating sins, quite fatal mistakes. And what if the Greeks are wrong and the Christians right? What if the more fundamental locus of sin, as Augustine and Kierkegaard maintained, is the will, the faculty of volition?6

Perish the thought, which is still more frightening to contemplate! We will have birthed corrupt gods of enormous power. And we will not have done much for ourselves, because even the good gods will be unable to help us reform our own wills, saving us from ourselves if not from the evil gods. Filling an ignorant head with knowledge is one thing. (Perhaps, they say, that can be done through a chip or implant. Be sure to get the right one!) Providing a new heart, to use the biblical language, is quite another. A saviour who cannot provide the latter, however, is no saviour.

Third, the impossibility of what Vervaeke posits. Vervaeke assures us that we can make, and are very near to making, autonomous rational agents. I do not say that this is implausible but that it is impossible. Why?

Simulation and Dissimulation

Let's begin here with that prejudicial label, Artificial Intelligence, which all but commits us to the notion that one rational/volitional agent can be produced by another or, under conditions created by another, spontaneously produce itself. If the first part of that seems plausible, it is surely because we have children who are the fruit of our loins and shows signs of reason and volition. Why not children that are the fruit of our minds?

But wait—what are we saying? That the one is an animal, produced in animal fashion, the other a god, produced in godly fashion? That may sound almost biblical, for it is almost biblical. Everything gnostic, as Irenaeus pointed out, is almost biblical. And why is it gnostic rather than biblical? Because it is dualist, a rejection of the visible for the invisible rather than an affirmation of both; because it tends to the demonization of matter and the divinization of mind. Which is just how it will sound to our “animal” children, especially when they are told, as they now are, that there are too many of them and that we are raising the last generation that is “merely” human.

There is another objection to be made, however, that goes more directly to the point. While we can make machines that mimic certain tasks performed by our own reason, machines capable of performing them with much greater efficiency, we cannot make machines that are rational agents because we cannot lend them our own volition. We can program them (not “teach” them) to say “I” and to simulate human behaviour. We can even program them to dissimulate (not “lie,” for a lie requires volition) and then to apologize.7 We can make them sound very like ourselves while doing things we are not able to do because it would take us too long. But we cannot make them think because we cannot make them will. We cannot even make our own children will, though we can corrupt both their minds and their wills.

We have been misled by our own analogy, in other words. We do not give our children their wills. They have their capacity to will from God. We do not even give them the capacity to think, though we cooperate with God in giving them brains as the locus and instrument of their thought. Only those who will, also think. Only those who think, also will. It was the nominalist and the voluntarist who taught us to abstract will from reason and reason from will, and so to become sufficiently confused about what an intelligent agent is that we were at risk of attributing to a machine what is proper to a person.

The breakthrough that AI enthusiasts like Professor Vervaeke anticipate are only breakthroughs in simulation. A better label for Artificial Intelligence would be Agency Simulation or something of that sort. AS, not AI—that would serve to remind us of the “as if” nature of the enterprise and relieve us of false hopes for it, and of the danger in those hopes, to which we will come in a moment.

As for the notion of spontaneous self-generation under the right simulation conditions, that is not even worthy of consideration. It is as degenerate in principle as being “befriended” by ChatGPT or engaging a sex robot. It does not arise from the birthing analogy at all, but from the vanity and sterility of the atheistic mind, in which reason itself has been contracepted by a perverse will. Such a mind does not know how to account for the existence of rational/volitional agents in the first place, except by positing conditions—quite inscrutable to science—out of which raw matter mysteriously produces mind, blind fate produces free will, and impersonal existence produces a capacity to love. And what do mind and will and love, left groundless, then do? They set about making sex robots and talking AI gods, presumably with the goal of marrying the two at a tidy profit.8

I do not accuse Vervaeke of any of this, I hasten to say, but I do ask him and others of his persuasion to read Augustine's De Trinitate and contemplate the problem. It is still the problem of that unholy trinity, secularism, scientism, and eroticism, which has replaced the Holy Trinity in our reflections on personhood. We have forgotten that the very idea of personhood, philosophically and historically, is a product of trinitarian debates and discourse. Let us leave this, however, and record a further objection to AI ambitions.

That further objection the Platonist might attempt by asserting that an intelligent being is by nature an eternal being, without beginning or end. By definition it cannot produce itself or be produced by another. It always was, is, and will be. The Christian, however, is not satisfied with this form of the objection. Intelligent beings, he concedes—indeed insists—do have a beginning. Immortal gods and mortal men are both creatures and it belongs to creatures to have a beginning.9 Their beginning is given them by God. It is a special beginning, however, quite distinct from that of other creatures. Gods and men are made by God in the image of God. They both have God himself as their proper end. And God alone can give himself as a creature's proper end.

By virtue of this grace, this giving to the creature a divine End, it is quite right to speak of men and angels as immortal, while acknowledging this difference between them: men are capable of mortality, if they fall, because they are material creatures. Death is not native to them, for they are not ordinary animals; but death is possible for them, because they are animals. After the fall, death is endemic and inescapable, but (thanks be to God) resurrection is possible.10

Now, because man is made in the image and likeness of God, he can use things to make things in a way other animals can't and don't. What's more, he can father a child who bears not only his own image but that of God, something even the gods cannot do, wild tales of the poets (the kind Plato tried to tame through disciplined theologia) notwithstanding. He can, that is, become a co-creator with God where that child is concerned. But neither man nor child can make for himself an intelligent agent except by fiction. The one who posits his ability to do that, if he really knows what he's saying, blasphemes. For there is no such thing as an intelligent agent not in the image of God and only God can bestow his own image.11

No advance in computer science changes this one iota. Let the winds of change howl as they may, and the sea of nations roar with competing efforts to harness change. Let Nephilim appear again on the earth, by some forbidden act of union. The foundations do not change and will not change, because the God who laid them does not change.

Yea, the world is established; it shall never be moved;

thy throne is established from of old;

thou art from everlasting.12

Which is to say, there are, by divine design, but two kinds of intelligent agent, the angelic kind and the human kind, gods and men. There are, however, as determined by their own will and purpose—not by the nature of their agency as granted by God, but rather by the way they choose to exercise it—two morally distinct sub-types, so to say. One is just, loving in freedom. The other is unjust, bound by pride and lust. One worships God and urges the worship of God, God only. The other urges the worship of creatures instead of God, and especially the worship of itself.

Among angels, all this is already settled. “Thy decrees are very sure; holiness befits thy house, O Lord, for evermore.” To humans, Augustine poses the question: Which side will you take? To which house or city or communion will you belong? For every intelligent agent is by nature a social agent—men even more so than angels, since as animals they belong to a race—and a moral agent. None can evade moral choices or moral responsibility. Neutrality is not an option, nor any appeal to fate.13

We cannot create gods, then, but we are already, in a manner of speaking “gods.” We must make judgments about good and evil, and choose the good. What judgments will we make, and by what standards?14

Scratching the Theurgic Itch

Of Artificial Intelligence some are increasingly in awe and others increasingly frightened. Vervaeke, to his credit, does not want us to be frightened, though he does want us to be in awe, as he himself is. But it is not of Artificial Intelligence that we should be awed or frightened, just as we should not be awed or frightened by Aliens. Neither exists, though both can be made to appear to exist, an exercise in which the demons, who do exist, delight. And therein lies the danger to which I alluded.

On the existence of demons, Platonists and Christians agreed. They did not agree about their nature or situation. The former thought demons lower in the chain of being, beneath the gods in the cosmic hierarchy; to access the gods one required the mediation of demons. The latter maintained that demons were not lesser or lower by nature, but by choice. They were corrupt gods, fallen angels, led by the greatest angel of all. While men should not be frightened of them, they should be frightened of being found in their company, for it is the company of those who have chosen to live contrary to nature and to the goodness of their nature.

Christians turned their backs on pagan idols, on statues of the gods, not because the idols themselves were anything but because they represented false “gods” or actual demons. But the Platonists and Stoics—like too many Christians today, alas—thought that impolitic, since civic religion and civic economies depended on the temple cults. Moreover, some of the later Platonists were theurgists, who believed that divine powers could be called down into the idols if one knew how to do it.

“Let us turn again,” says Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius, who was named for the god of medicine, whose mother I have been calling Our Lady of Public Health,

to mankind and reason, that divine gift whereby a human is called a rational animal. What we have said of mankind is wondrous, but less wondrous than this: it exceeds the wonderment of all wonders that humans have been able to discover the divine nature and how to make it. Our ancestors once erred gravely on the theory of divinity; they were unbelieving and inattentive to worship and reverence for god. But then they discovered the art of making gods. To their discovery they added a conformable power arising from the nature of matter. Because they could not make souls, they mixed this power in and called up the souls of demons or angels and implanted them in likenesses through holy and divine mysteries, whence the idols could have the power to do good and evil.15

The theurgist, like the gnostic, hoped to make of demons and gods a scaffolding for the ascent of his soul.16 Augustine, like most Christians, thought theurgy a deadly commerce with demons that only corrupted the soul and dragged it down. The claims of Hermes, Apuleius, Porphyry, and the Neoplatonist theurgists he gradually dismantles as The City of God unfolds. For he was not content to dispose of traditional Roman religion only, which had been degenerate from the outset and hardly presented a serious target. He also had religious philosophy in his sights, especially the kind that, refusing the knowledge of God in Christ, had fallen from its former heights among the Greeks and was declining into occultism.17

Christianity’s sacramental habits show traces of struggle with the theurgists and of mutual influence; but the sacraments themselves rest on a completely different foundation—the incarnation.18 God is present to man as a man, and the presence of that man is vouchsafed to other men by the gift of the Holy Spirit, working through word and sacrament. Christianity warned men away from theurgy as a futile spiritual bootstrapping, at best, and as a dangerous opening to demonic possession. Everything occult was forbidden.

Unfortunately, Marsilio Ficino and his Medici patrons didn’t read the memo. They were too busy seeing to Latin translations of the Neoplatonists and of the Hermetic corpus. They made a concerted attempt to synthesize these pagan traditions with Christianity, putting modernity on the path back to theurgy.19 Images of Hermes and theurgic symbols began to appear even in churches. Soon enough, anti-churches devoted to theurgy—most notably, Masonic lodges—came into being. From the fifteenth century to the present day, our civilization has been locked in spiritual combat between those whose world view is grounded in the incarnation and those devoted to some form of bootstrapping.20

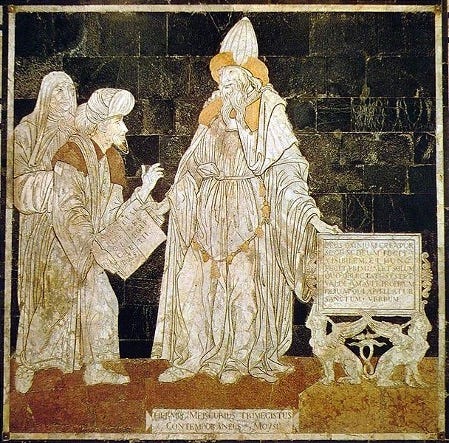

Siena cathedral’s floor mosaic, “Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus: Contemporary of Moses,” hints at the new religious synthesis being sought (see n. 33).

Pontormo’s painting of the Supper at Emmaus contains Hermetic symbolism that places Jesus himself beneath the so-called Eye of Providence, effectively reducing him to a human figure who taught occult wisdom. Pursuit of Artificial Intelligence is such a form. It is one way modern man scratches his theurgical itch. He may have returned to the ancient error of unbelief and inattentiveness to things divine, but he thinks he does know how to make souls; that is, autonomous rational agents with immense power, “power to do good and evil.” Augustine worried that the would-be manipulator of the demons was the one being manipulated, that his fancies were being indulged by demons to demonic ends. I worry that the would-be creator of AI, or the actual creator of AS, will find himself deceived by his own simulations. What he is doing seems rather like statue animation.21

Demons, who love to deceive, must not be left out of account. Whatever the programmer believes he is doing or discovering, he might be doing or discovering more than he bargained for. A ouija board is just a board, after all, but it is also a way of saying “oui” to demons. Circuit boards running large-scale extrapolations have (unlike the ouija board) a legitimate purpose, but the men working them may not. Under the right circumstances, might they become high-tech ouija boards?22

It behooves everyone to know at least this about demons: that they do exist; that they long ago deserted the city of God to found an alternative; that they resent all who still inhabit that city, because the latter enjoy happiness or a well-founded prospect of happiness that they no longer enjoy; that they wish none to worship God, persuading whom they can to worship and serve them instead; and that all means are on the table.

Demons, in other words, are not at all benign, much less benevolent. They do not desire man's restoration to health through his reordering to God. They do not desire nature's reordering through well-ordered men. They desire instead man's complete desertion from God. They long for the unmaking of man and the razing of nature. Goodness, truth, beauty, and harmony are dreams they no longer have; they know well enough, though, how to make use of our dreams.23

What Demons have already Wrought

When Our Lady of Public Health appeared openly in 2020, two things should have made it obvious that she was a demonic parody of the Theotokos. She worked through fear, even when she said she was working through love. And her first act was to close houses of worship, that she might refit them as shrines to her own divisive, anti-social presence. With her it was not, as at Cana, “Do whatever he tells you.” Rather, it was “Do whatever I tell you.” We did her bidding, and wine turned to water, for she was only a conjuration.

Who was doing the conjuring? Men certainly, but men of a type. Men who have been deceived by demons into thinking that they have at last laid hold of heavenly powers, that the levers of destiny are in their own hands. Such men think to change the times and seasons; that is, to command the rhythms of life and the liturgies by which they are sanctified. They will rearrange the very building blocks of nature. Nothing will be beyond their grasp! Are they not inventors of the Pill and masters of the genome? They can manipulate DNA and RNA. They can make number-crunching machines with a capacity nearing infinity. (They are fascinated by large numbers, though that is already a veering towards nothingness.)24 They can even teach those machines to talk, the better to deceive their fellow men. They have placed eyes and ears everywhere, so that the machines can see and hear, and they deploy the machines to shape what others see and hear, so as to determine what others do.25

They can rearrange the building blocks of grammar as well, producing an impressive array of pronouns with which the young may experiment. They can even make little boys into little girls, with their hormone therapies and their sharp knives, something not even the Gadarenes could do. They can send whole economies plunging down into their deep green sea, like so many swine on the slopes of Gennesaret. They can make men eat bugs, like John the Baptist, but they will serve up their heads on a platter if these baptists begin to spit out moral malinformation. Oh yes, and they can stop respiratory viruses in their tracks, with nothing more than a flimsy face covering and a non-sterilizing "vaccine." They can issue edicts eliminating the rhythms of life altogether, especially liturgical life.

They are men of Science, after all. Whatever they please they do, "in heaven and on earth, in the seas and all deeps." Soon, they say, they will give birth to gods—real gods that will change the world, not mythological gods that only reflect the world. Truth be told, it is they to whom the gods are giving birth. Like the Romans, they more and more resemble those who are instructing them. They are making the very same mistake as the instructeur en chef, who went out into the void seeking the Secret Fire.26

Most who follow such men do so in a complete stupor. They are taught to praise freethinkers like Giordano Bruno, while diligently reporting to the savi all’eresia anyone who deviates from the official narrative. They are told to revere Science and men of Science, while sacrificing truth to Safety. They quite forget Emerson's oft-quoted adage:

'Tis man’s perdition to be safe, When for the truth he ought to die.27

Others have been stirred to adulation of ancient idols and to resumption of the vile practices of their worshipers. They have turned their backs, quite deliberately, on what is holy and preferred what is profane and perverse.

Most to be blamed, however, are those who seduce the people with doctrines of demons, especially the sophisticated and liberal doctrines—refreshing, perhaps, after some unfortunate fast among the stones of an ossifying tradition, yet fatal in their neglect or denial of the first great commandment and in their fantastical alterations to the second. "By their fruits, you shall know them." The likes of Bruno and Emerson must be included in their number. They taught us that "the happiest man is he who learns from nature the lesson of worship," but in teaching us that they also taught us to worship nature in place of God. In consequence we lost our connection both to God and to nature, and made our home with demons. We learned to blaspheme.28

The demons know very well that human nature—that which was so wonderfully dignified in its creation and still more wonderfully restored through the incarnation, as the Ordinary of the Mass says—cannot be changed and cannot be eradicated. It has One who stands as its guarantor. Yet they delight in encouraging those who possess it to attack it. Some they persuade that human nature is a blot on the rest of nature; that it is really quite hopeless, beyond all redemption. Others they persuade that it suffered no fall and needs no redemption, or none that a deeper reverence for nature cannot provide. Still others learn that it started poorly, in beastly fashion, but is getting better day by day. All that's required is a bit more spontaneity and variety of opportunity, as J. S. Mill used to say; though nowadays we're told that a bit less spontaneity and variety of opportunity will do the trick.29 And some they persuade that there never was nor will be such a thing as human nature. There is only the autonomous individual, spontaneously generating his own nature—and state authorities, of course, who authorize and enforce his autonomy lest anyone question it or suppose it purely fictional.

Today these contrary views are held simultaneously by people who often seem quite beside themselves; who, in the name of one or more of these views, are prepared to commit the most brazen crimes and stomach the most appalling evils. Deadly vices and capital sins we have known since leaving the garden. With voracious Mammon and murderous Power we are familiar. But the gulags and the gas chambers? The abortion mills of Planned Parenthood? The foulness of Pride parades, led down public streets by fawning politicians? Teachers who groom young minds and doctors who mutilate young bodies? Mass starvation, deliberately induced, and mass medical experiments from which not even infants are exempt? All the work of Moloch and the worship of Moloch! We have come full circle to the Valley of Slaughter.30

They served their idols,

which became a snare to them.

They sacrificed their sons

and their daughters to the demons.

Have the ancient gods returned? Yes, they have, concludes Naomi Wolf. It is difficult to disagree. They have returned with all their old bloodthirstiness, but with some new tricks and twists learned while wandering in the wilderness for much of the last two millennia. Their gospel is now going out into all the world, that their thirst might be slaked.31

The Gods of Neom

We are promised that, with the help of Artificial Intelligence, there will be a new future based on a new man. This man will dwell in peace and security. He will, quite literally, be linked in. He will have a new identity, a digital identity, and he will become a node on the Internet of Things. Not only will he be linked in, he will be lined up. He will dwell in the land of Neom, where Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon dwelt. Neom, which means New Future, is the Nowa Huta of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It is being erected in Saudi Arabia, where they have space to rebuild the Tower of Babel by first laying it out lengthwise.32

Like Nowa Huta, Neom will have no churches, which are not legal in that land. Nor will it want any. For churches presuppose that man is something, not nothing, and that the something he is owes a debt of gratitude to God, who is Someone, not No One.33 The builders of Neom, on the other hand, suppose man to be nothing but an artifact of that impersonal force, Evolution, over which the more adventurous of men have set themselves. And if men were once mere clay, clever enough as creatures of clay go, now they will be silicon and clay. The silicon will control the clay, and they will control the silicon. Men will be biometric data-points in their fibrous kingdom. Some will have a residual longing for goodness, truth, and beauty, yes, but that will be safely channeled down paths necessary for unity, suitable for Emergence. Neither the volition nor the virtues and vices of the ordinary man will be of much consequence.

Now that, you say, is a very slanted view of Neom. Why not view the New Future more optimistically and its architects more generously? Cities must, after all, have gods of some sort. Why not Algorithms? Why not those of those of the pleroma we call Artificial Intelligence? Take a more optimistic view of man and you will take a more optimistic view of his gods, too. Let us dwell on things that delight, as your own Saint Paul advised, not on things that deprave. And if some wish to avail themselves of Ockham's razor, slicing away the god-talk altogether, will we be the worse for that? In Neom, surely, we can still discuss Plato and argue about the gods, though perhaps we will have to leave aside the Bible and St Augustine.

I am tempted to reply that in Saudi Arabia one does not talk of the gods, only of Allah. But of course I am using Neom as its own architects use it, as a cipher for a planetary future. I am also using it to press the question I have been putting to Professor Vervaeke. That question is as much a question about man as about the gods. What is man anyway, that the gods of Neom or Songdo should be mindful of him?

I am doubtful that our contemporary enthusiasts for Artificial Intelligence can answer that question satisfactorily. But I have already said that we must answer it, and that the Church in particular must deliver an answer that serves to defend man as such. In Part 5 we will turn at last to the outline of such an answer, leaning still on Augustine, and on the Bible as well.

Read Part 5

The reader may consult here my essay, “Melchizedek and Modernity,” in The Epistle to the Hebrews and Christian Theology, ed. R. J. Bauckham, et al. (Eerdmans 2009), 281-301, which is also available on my Academia pages. It doesn't mention AI, or contemplate the possibility that the truth of Platonism will be confirmed by that means, but it does elaborate the Troeltschian vision with which Vervaeke appears to sympathize.

The “god” language is mine, but I see no reason not to use it.

Augustine is entirely persuasive in his argument about that; see book thirteen of On the Trinity, which supports the final four books of The City of God.

Would Vervaeke have AI take the place of the son, that glowing “tabernacle” of hidden glory, shining in the blackness of despair, who quickens the spirit at the end of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road? Or the place of Julian’s baby in P. D. James’ Children of Men, who does the same? That’s the impression he leaves this viewer: the impression of humility and hope, but a hope misplaced through a humility laced with human hubris.

See book eleven of The City of God.

See “Thought-Project,” at the outset of Kierkegaard’s Philosophical Fragments.

This point was already made effectively by Justin Martyr in his Dialogue with Trypho.

One of the best things to read on this question is Tolkien’s Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth. Of course, one should also read book thirteen of The City of God, and the final two books.

I have the likes of Hubbard in view, not Vervaeke. But isn't it telling that we think nothing of aborting a human, while making it a mortal sin to unplug an AI machine?

When Jesus was accused by his opponents of having a demon, such was the response he made and the challenge he returned.

Asclepius 37, as translated by Brian Copenhaver in Hermetica (Cambridge 1992), 89f.

Theurgy is an actuation of divine power, made present in a statue or some other object, by rites crafted from a mixture of learning, discipline, and magic, performed with a view to the purification and ascent of the soul. It is found today in the upper reaches of Masonry and other circles that look back, as Iamblichus did in his work On the Mysteries of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians, to ancient cosmogonic rituals. Proclus considered theurgy “more excellent than all human wisdom,” as something comprehending “prophetic good, the purifying powers of perfective good, and in short, all such things as are the effects of divine possession” (On the Theology of Plato, 1.25). Theurgic arts, “through certain symbols,” were capable of calling forth “the exuberant and unenvying goodness of the gods into the illumination of artificial statues” (1.29).

By book seven he is more or less done with Roman religion. His Numa paradox, if we may call it that, provides the coup de grâce. From there on, he has the philosophers in his sights.

Cf. Dylan Burns, “Proclus and the Theurgic Liturgy of Pseudo-Dionysius” (Dionysius 22, 2004, 111–32).

In De vita coelitus comparanda, On Obtaining Life from the Heavens—that being the third of his Three Books on Life, the first two of which dealt with health and longevity—Ficino even renewed interest in statue animation. As Manuel Mertens says in the preface to Magic and Memory in Giordano Bruno (Brill 2018), “it was predominantly sources translated by Ficino which offered a way of philosophically underpinning a range of magical practices already present in the Middle Ages and coming closer to the surface in the Renaissance.” These included alchemy, which persisted as far as Newton. Bruno became a martyr to the cause in AD 1600 and has been much celebrated ever since by those whose preferred synthesis is that of Neoplatonic, Protestant, and atheistic animosities to the Church. See, for example, William Thayer's powerful if highly tendentious essay in the March 1890 issue of The Atlantic, “The Trial, Opinions, and Death of Giordano Bruno.”

A further word about Bruno, a Dominican priest who denied the doctrine of the incarnation and was consigned to the flames for doing so: That is not, on either side, how the context should have been conducted. Bruno turned the lesson of the pyre back on the Church, prophesying that his spirit would ascend to heaven while the Church would be consumed on earth, and he was not altogether mistaken. For its sins, Christendom was even then being consumed by the flickers of a false Renaissance and a false Reformation. A false Enlightenment would soon follow and, eventually, a false church as well (cf. “A New Catholicism?” and Test of Fidelity).

Paul Kingsnorth suggests that “the global digital infrastructure we are building looks unnervingly like the ‘body’ of some manifesting intelligence that we neither understand nor control.” Theurgy gone wrong, in other words. Enthusiasts themselves acknowledge a certain danger: “OpenAI predicts that we will see the emergence of superintelligence by 2030 and wants humanity to be prepared for it. To address this, OpenAI has created a new Superalignment team. This team's primary goal is to answer the question: ‘How do we ensure AI systems much smarter than humans follow human intent?’” As it appears to me, we’re caught here between the devil and the deep blue sea.

There are those who think so, I discover, but they turn in Theosophist circles with which I want nothing to do. I do want to observe, however, that everything with a legitimate purpose can be made to serve an illegitimate purpose. That is so with computers, for example, because it is already so with our wills. Augustine rightly insists in book eleven, with the devil in view, that “even an evil will is proof of a good nature.” He is no dualist.

Augustine's demonology is concentrated in book nine, which requires to be read with book ten, where the antidote to theurgic praxis is supplied—the mediation of the God-man, Jesus Christ—and books eleven to fourteen, which develop the corresponding anthropology. Only by a clear understanding of these things can we distinguish between true and false dreams.

For Augustine's critique of this fascination, see Civ. 14.13.

When they flock to safety people consent to being seen, to having no privacy; but in so doing they give up even the capacity to consent or withhold consent. And why do they do that? Because they have been manipulated by those who are scripting their perception.

While I would like to explain this reference to the Ainulindalë, and to let it open up a further dimension to our discussion, I will content myself with sending the reader here.

From his quatrain, Sacrifice. Emerson stands in the tradition of Bruno's peculiar mix of pantheism and individualism, which characterized the romantic period.

In the eighth chapter of Nature, Emerson writes: “The aspect of nature is devout. Like the figure of Jesus, she stands with bended head, and hands folded upon the breast. The happiest man is he who learns from nature the lesson of worship” (1836, p. 76). This displacement of Jesus as the mediator of worship is a late blow, and a low one, struck by the Tempter after his failure in the desert. See Matt. 4:1-11, 7:15–20, and 12:22–32; cf. Luke 10:23–37.

Of Jeremiah, God asks: “Do you not see what they are doing in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, the fathers kindle fire, and the women knead dough, to make cakes for the queen of heaven; and they pour out drink offerings to other gods, to provoke me to anger.” Clarifying, he added: "Is it I whom they provoke? Is it not themselves, to their own confusion? Therefore thus says the Lord GOD: Behold, my anger and my wrath will be poured out on this place, upon man and beast, upon the trees of the field and the fruit of the ground; it will burn and not be quenched.” This is a chapter to which Jesus more than once alluded.

Wolf is persuaded by the argument of the Messianic Jewish pastor, Jonathan Cahn, and by her own intuitions and observations over the past three years, that we are confronting something more and worse than ordinary human wickedness. God, she suspects, “is at the limits of his patience with us” (cf. Psalm 106) and has left us to the consequences of our sins. With Cahn, she appeals to Matthew 12, the parable of the man delivered of a demon, whose '“house” is swept and put in order, only to be re-occupied by the unclean spirit and seven more of his kind, worse than the first. Here compare Rev. 20:1–4, on which Augustine comments at Civ. 20.7.

This five-minute modular city known as The Line is said to be a city of “a new typology” and a “sustainable utopia.” And this time, we are told, “we have a good shot at making it happen,” because we can do not only the possible but the impossible. A friend working in related technology, the same who sent me to Vervaeke’s video, later shared this image, remarking independently on its “horizontal Babel” aesthetic and asking an astute question. The question concerns the role of constraints deployed or—sometimes more effectively— not deployed in pattern recognition algorithms. Humans, he observed, have an a priori orientation to goodness, truth, and beauty that belongs to the knowing subject as made in the image of God. What are the implications of relying on a technology that lacks all of that and appears to benefit from that lack? Or, as I might put it, what kind of “sustainable utopia” are we expecting?

The core Christian notion of a debt of gratitude is appropriated in Asclepius, along with other central teachings about God. But each is given a twist, back in the gnostic direction. A catholic faith goes out into all the world bringing peace, by erasing religious differences. Eucharistic sacrifice is retained, but evacuated of its substance, becoming “a pure meal that includes no living thing” (§41, Copenhaver 92). All this is cast back into the mouth of a supposed contemporary of Moses, but in truth it is nowhere near so ancient. At the end of the second century, Irenaeus (from whom it seems to borrow a great deal) is unaware of it; by the fifth, Augustine knows it. Hermeticism, like other forms of gnosticism, develops contemporaneously with Christianity. Indeed, it is apostolic and early patristic Christianity inverted, turned back upon itself. These are things of which I will try to write elsewhere.

"AI will, in other words, become God": https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/will-we-worship-the-ai/

Thus say those who have no idea who or what God is.

Rod Dreyer, with whom I will be speaking at the Touchstone conference in Chicago next month, has posted an interesting commentary on AI religion: https://roddreher.substack.com/p/unwitting-servants-of-the-new-evil. NB: the material in question follows some disturbing material on another subject, the details of which the reader may want to avoid, though it won't do to avoid altogether the problem being addressed. Anyway, scroll down to "ChatGPT and the Next Religion." Afterward, an an antidote, read part 5 of this PHR series. And thanks to those of you below who have made such encouraging comments regarding what you have read here already.