Part 1: Our Lady of Public Health

Part 2: The Global Protection Racket

Part 3: Our Lady's Secret

Part 4: Doctrines of Demons

We have been speaking of the Public Health revolution, in which concern both for individual good and for the common good has become narrowly focused on health, while “health” has come to mean whatever the revolutionaries wish it to mean, whatever makes it useful as an instrument of governance.

We attended to the framing of health as a matter of state, ultimately as a planetary affair, and to the reversal of the principle of subsidiarity effected by that framing, such that decision-making even about individual good is transferred to ever more remote levels of governance.

We noted the willingness of soi-disant men of destiny to take charge of health and to do evil that “good” may come—to commit crimes against others in the name of the state or of the planet, even to the pursuit of agendas for depopulation. We discerned a variety of motive forces, from raw greed to eugenic hubris to a sense of desperation, swelling up from some current of despair running deep beneath the surface optimism and spreading in waves of panic.

We touched briefly on the false doctrines that led to all this, on the return of the baalim and of theurgic impulses, on the delusion that we can be our own saviours or through “artificial intelligence” fashion gods who will save us. We have become like those idol-makers mocked by Isaiah, though we use fancier tools.1 We have made ourselves prey to malign forces promising health and safety but bringing disease and destruction.

Where shall we turn? Politics, medicine, and law have all been corrupted or shown to be corrupt; in the universities, as in the media, “science” is for sale and propaganda prevails. There is treason afoot in the corridors of power and a gathering crisis of authority. Fear-mongers continue to ply their clamorous trade, padding the wallets of global profiteers. Bankers plot to lighten our wallets by substituting digital tokens for cash. Psychosis is common; in some quarters, including school boards and town councils, madness has set in.

There is method behind the madness, yes. In some spheres, an illusion of choice is created where there is no choice, to cover the loss of choice where there ought to be choice.2 In others, disaster or threat of disaster is introduced to batter the collective psyche. Generating instability, chaos, and terror is a proven formula, after all, for effecting a revolution. Madness can also be feigned, though too often now it is real. Very ordinary people, in very ordinary roles, are doing very extraordinary things, unaware of why they are doing them but supposing them to serve that which manifestly they do not serve: health and wellness, health and security, health and happiness.

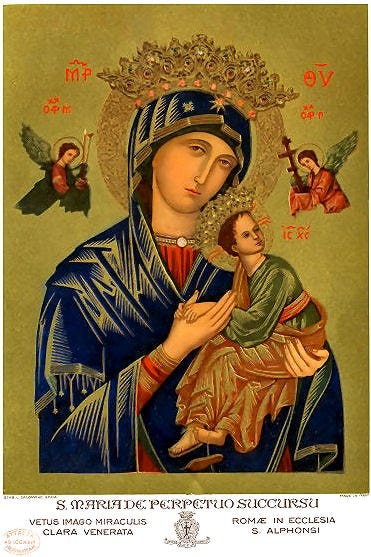

Meanwhile, Our Lady of Public Health promises her unfailing aid. Even now she is dangling masks like rosaries and rumouring another retreat conducted in the quiet of our homes, where we may venerate her without interruption. Soon, she hopes, she will replace our homes with “smarter” accommodations that make possible a more permanent retreat, a new monasticism for a new world. Her every apparition is an assault on liberty. She is a parody of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. She attacks the mind with contradictions, the soul with fear, the body with biowarfare. Yet people turn to her, joining her cult of needles and knives. They look to her algorithms for wisdom, her providence for daily bread. A religious fervour agitates the vast Pool of Bethesda that is Public Heath, beside which an increasingly dysfunctional populace is told to lie and wait for salvation.

Robert Bateman, The Pool of Bethesda (1877)

We lie and wait, because we did not stand and watch. Overtaken by spiritual lethargy, we did not put up much resistance as the moral underpinnings of our civilization were assaulted. Now we are confronted by men with a demonic hatred of the human, who take pleasure in mocking the holy.3 What answer shall we make to them? What shall we say or do in rebuke of the apparitions they conjure and the agitations they undertake? How shall we repudiate our Lady of Public Health?

Obviously we must refuse her every offer of assistance. To accept it is to concede needs we don’t have and an authority she only pretends to have. We must refuse to take the veil or make the vows. We must reject orders that conflict with the practice of our faith, or with the constitutions to which we have consented, or with the true good of our families and neighbours. Against the mighty—those men of obscene wealth and their power-hungry collaborators in the military or the civil service or in high office—we must put up the weak, mounting our freedom convoys and organizing, as best we can, alternative socio-economic structures.4 Against the men of Science we must put up the men of common sense, recalling what Chesterton said a hundred years ago about that modern idol: “The thing that really is trying to tyrannize through government is Science.” We must, as he proposed, become pioneers again, this time in a still more hostile environment. Civil disobedience will be indispensable.5

Above all, however, we must put up truth. Truth, and the reason for the hope that is in us. This does not mean a defence of God, who needs none. It means a defence of man, whose need has never been greater. And man, in the last analysis, has only one defence, the defence God himself has offered. Of this truth, the most important truth, we will now speak, in hopes that some, at least, will hear the Voice with power to say, “Rise, take up your pallet, and walk.”

Palma il Giovane (1592), Jesus healing the paralytic

What is man, that Thou art mindful of him?

When contemplating anything made, says Augustine, we should ask three questions: who made it, by what means he made it, and why he made it. That is a simple and salvific art, proper to all who care about truth.

Of the world, the answers Augustine gives are that God made it, by means of his Word, because it is good. The world is good because God is good. It exists because God is generous. It coheres because his Word lends it coherence. It is beautiful because his Spirit adorns it with beauty. It is to be gratefully received, not feared or appeased.

Of the city of God, whose citizens give thanks for their daily bread and praise God for his goodness, of the city destined to inherit the earth and the kingdom of heaven, Augustine says something similar.

How does it come to be? God founded it… How does it come to be wise? It is illumined by God... How does it come to be happy? It enjoys God. It is defined by subsisting in God; it is illumined by contemplating God; it is made joyful by clinging to God. It is, it sees, it loves. It finds its strength in God’s eternity, its light in God’s truth, its joy in God’s goodness.6

The same kind of answer is given regarding man; for men, together with angels, make up the city of God: God made man. God made man by his Word. God made man, illumined by his Word, to enjoy what his Word enjoys; namely, communion with the Father, a good than which nothing could be better. The city of God is “that most orderly and harmonious society to be enjoyed with God and, mutually, in God.”7

The one who thinks these answers too theological to be of much use should think again. Why have so many people, even Christian people, been seduced by Our Lady of Public Health? Why swept away by waves of panic about themselves or the planet? Because they have forgotten these answers or become unsure of them. In short, because they have been overcome by secularism and scientism and eroticism. They do not know who made us, or how we were made, or what we were made for. They no longer see man as the marvel he is. They see neither the majesty of God nor the wonder of man. Hence they have no bulwark against their foes.

“O LORD, our Lord,” says the psalmist, who knows that God has established a bulwark of praise even in the mouths of babes and infants, “how majestic is thy name in all the earth!”

When I look at thy heavens, the work of thy fingers,

the moon and the stars which thou hast established;

what is man that thou art mindful of him,

and the son of man that thou dost care for him?Thou hast made him little less than God,

and dost crown him with glory and honour.

Thou hast given him dominion over the works of thy hands;

thou hast put all things under his feet.8

God is mindful of man. How does he defend the marvel that is man? How does he display his faithfulness to man? The biblical narrative tells us. He rescues Noah. He calls Abraham. He befriends Moses. He raises up David. He provides a tabernacle, a tent of meeting, that men may know, not only that there is a God—something no man, whatever lies he tells himself, does not know9—but who this God is. He does not merely meet man in the tabernacle. In the fullness of time he makes himself the tabernacle. “The Word became flesh and dwelt (ἐσκήνωσεν, tabernacled) among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father.”10

The biblical view of man, who is made from the dust of the ground and from the breath of God, is that he is both small and great, and has as yet only small knowledge of that in which his true greatness consists.11 He has been shown that his highest good, his summum bonum, is life before God and with God. He has been told that it will also be life in God, a sharing in the divine nature. That is the inestimable privilege made possible by the incarnation. Man will know God with God’s own knowledge of God and glorify God as he ought to be glorified. He will become a true likeness of God and an undistorted reflection of the divine Glory. No man is fully alive until he beholds God, and to behold God is the goal of man. In that beholding, says Augustine, “we shall be still and see, see and love, love and praise!”12

Now, this view is not romantic but realistic. In no way does it neglect human frailty. Nor is it the least naïve about sin or the fall, which is not mere frailty. On the contrary, it faces both with all frankness, recognizing them for what they are. It is also capable, then, of looking death in the eye. It can do so, without fear, because it sees that God’s defence of man goes all the way down.

The Son of God deigned to enter the Virgin’s womb. The Word of God, though himself “in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.” That—surpassing the astonishing grace of creation itself—is the Great Generosity. It is God’s first defence of man, the defence that addresses human frailty, fortifying humanity with divinity, human nature with the divine nature. The second defence is still more profound, addressing human sin and its consequences:

And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.13

The divine defence, in other words, not only goes all the way down but all the way up. In this one Man it exalts man as such. It declares the faithfulness of God by exposing both the feebleness and the greatness that is man. God takes the side of man. He takes the place of man under condemnation. He delivers man from bondage through fear of death and deprives the enemy of man of his greatest weapon against man. He reclaims man and shows himself the Lord of man.14

Had man not fallen, he would have needed no lord but God himself. Having fallen, however, he requires a lord who is also a saviour. Every would-be lord thus styles himself Soter, as the Caesars did, and as our own aspiring lords do. How do they go about it? By pretending to take our side while taking sides against us. By making us afraid and then promising us relief. By exaggerating our weaknesses that we might praise their strengths. They tell us we are unhealthy, that they might make us healthy; that we are broke, that they might lend to us; that we are in danger, that they might secure us; that we are faulty, that they might fix us. Just so, they disparage both us and the One who made us, as if we were faulty creatures rather than fallen creatures. We are not faulty. On the contrary, we are wondrously made.15 We do need a saviour and a salvation, but we do not need them or their salvation. They themselves are “in subjection to invidious powers” and wish to keep us in subjection also.16

The Saviour we need, we already have. The Lord we need, we already have. Therefore we are free. No truly effective answer to those would enslave us can be given by those who do not know the ground of their freedom. The answer that can be given, and should be given, is the same answer given the German authorities at Barmen in 1934:

As Jesus Christ is God’s assurance of the forgiveness of all our sins, so in the same way and with the same seriousness is he also God’s mighty claim upon our whole life. Through him befalls us a joyful deliverance from the godless fetters of this world for a free, grateful service to his creatures.

We reject the false doctrine, as though there were areas of our life in which we would not belong to Jesus Christ, but to other lords—areas in which we would not need justification and sanctification through him.17

Public Health tries to establish such areas. It will justify or refuse to justify. It will give or withhold permission to the people and even to the churches. But it is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Since he has saved us, those who have not saved us have no permission to enslave us in order to “save” us.

Mediaeval flyleaf (1439) showing Augustine preparing his answer: Mockery from the city of man elicits from the city of God a reasoned response. What the one vituperates the other illuminates.

What is man and who is the lord of man? The secularist refuses the question, but the saeculum itself is precisely for asking and answering it.18 Those of whom we are speaking have already answered it. Man is merely a creature of clay and they are his lords. On their account, the difficulty with man is not that his rational soul no longer obeys God, with the just consequence that his body no longer obeys his soul and he begins to disintegrate physically, psychologically, socially. Augustine is mistaken about all that. The difficulty with man is man himself. Man does not need a mediator with God, a Great Physician who takes up his humble estate so as to restore him to health of soul and body. There is no God, nor Great Physician, and man has no soul. They will give him one, a silicon soul that they themselves shall possess and whose every secret they will know. They will persuade him to receive it by the promise of health and safety, of peace and security, even of happiness through detachment from worldly goods, the burden of which they will carry for him. But they can only deliver on their promise by evacuating all these words of their meaning. Is it not time, then, that we rediscovered their meaning by rediscovering the one who actually is Lord, and becoming mindful of him?

A Crisis of Authority

This is not the answer most are calling for, I know. It makes no fatal concession to secularism or scientism. It is not content with a reaffirmation of democracy in the face of kleptocracy, or of “people power” against technocracy. It is not mere insistence on human rights and freedoms, as necessary as that may be. It is first and foremost an acknowledgment of divine rights, of true lordship, of genuine authority; hence also of our liberation from false and oppressive lordship.19 It takes account of who made man, and how, and for what purpose. Any answer that fails to do that falls short and is not fit for purpose.

I am not sounding a general retreat to my own discipline, theology, or to my own faith, the Catholic faith. I am not saying that the answer given can afford to be “only” a theological answer. On the contrary, it must be an answer delivered by courageous men and women labouring in the sphere of medicine or public health, in the law of the land or on the land itself; men and women working against corruption and tyranny in every walk of life. I am saying, however, that no answer or set of answers that refuses to be theological at all—that tries to evade the question of authority and the proper grounding of authority—can hope to be adequate.

Inside the Church and outside the Church, we are embroiled in a crisis of authority that goes to the very roots of authority. Justice has seen to this, as the consequence of our grievous violations of natural and divine law. Providence has permitted it, as a pressing invitation to faith and repentance. To decline the invitation would be folly. To forget that there is no genuine authority but what comes from God, and that God has vested all authority in the Christ, to whom every lesser authority will be held accountable, is to court disaster. Not for nothing did Jesus adopt the title “Son of Man,” with its davidic overtones. Not for nothing did he frame his final instructions in terms that recall Daniel’s famous vision of one coming before the Ancient of Days to receive “dominion and glory and kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him.”

All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age.20

Note his reference to the close of the age. It is a great mistake to suppose that things can go on indefinitely as they have been going; the revolutionaries are right about that. It is an equally great mistake to think that things can stand still, or go backwards, or just go round in circles until the eventual extinction of the race. That is false, as the doctrine of reincarnation is false. Going round in circles is a preliminary form of judgment, whether of men or of their civilizations, but it is not all there is to judgment. It is a feature of human history, but not all there is to history. Just as it is “apportioned to men once to die and after that to face judgment (κρίσις),” so it is apportioned to history to find issue in a decisive contest and a final victory.21

The present age is, and has been since the ascension of Jesus, the last of the ages. It is a time for decision, not for postponement of decision. “Choose you this day whom you will serve,” said Joshua to Israel. Choose you this day whom you will serve, says Yeshua to the nations.22

In making that choice, we do well to remember that the source of all authority is one and the same as the source of all happiness. This age and the span of each man’s life within the age—beware! we know the length of neither—is an opportunity to receive or reject the prospect of happiness, which all men want. To attain to happiness, Augustine insists, we must learn to want rightly.23 We must learn to want what God in his goodness, beauty, and truth wants for us. If we do want it, we shall have it, and have it immortally.24 If we don’t want it, we shall in the end have nothing we want. We will arrive, not at our summum bonum, but at the summum malum, our greatest possible calamity.

Augustine does not want that to happen, so he proclaims to us the gospel, in words worth repeating to those demoralized by a revolution that knows nothing of immortal happiness and seeks through fear of death to put all men under the feet of a few men:

Nothing was more needed for raising our hopes and delivering the minds of mortals, disheartened by the very condition of mortality, from despairing of immortality, than a demonstration of how much value God put on us and how much he loved us. And what could be clearer and more wonderful evidence of this than that the Son of God, unchangeably good, remaining in himself what he was and receiving from us what he was not, electing to enter into partnership with our nature without detriment to his own, should first of all endure our ills without any ill deserts of his own; and then once we had been brought in this way to believe how much God loved us and to hope at last for what we had despaired of, should confer his gifts on us with a quite uncalled for generosity, without any good deserts of ours, indeed with our ill deserts our only preparation?25

Thus valued, thus defended, thus loved, man has a well-founded hope, a hope that springs eternal. He is therefore irrepressible.

Believing man a creature loved by God with such profundity, Augustine thought there must be more men, until the full complement requisite to the glorious architecture of the city of God is made up by those preferring the path of humility to the path of pride, the path of gratitude to the path of rebellion, the path of hope to the path of despair. He was an ardent defender of the freedom to choose.26

Our luminaries today think there must be fewer men, and fewer still who think or choose for themselves, who are free to love with a godly love. Hence they are busy dissolving families and faith communities, dismantling democracies and digitalizing identities. They are for census and censorship. They are working to an altogether different blueprint, a diabolical blueprint on which men have numbers rather than names, fates rather than freedoms.27 To obscure that very fact, they are building a therapeutic society, a pharmacological society, a society beyond politics and beyond morality. They have chosen the path of pride, rebellion, and despair. As for the Christ, of him they say quite emphatically, “We will not have this man to rule over us.”28

But he will rule over them. He already does. They may deceive with their secularism and corrupt with their eroticism. They may fool with their scientism, urging “as true what they know to be mere illusion.” Thus do they “tighten the bonds of civil society, so that they might likewise tighten their hold on their subjects.”29 The Lord God, however, knows what they are up to. “He searches out the abyss, and the hearts of men, and considers their crafty devices,” which in due course he will bring to naught.

For the Most High knows all that may be known,

and he looks into the signs of the age.

He declares what has been and what is to be,

and he reveals the tracks of hidden things.

No thought escapes him,

and not one word is hidden from him.30

The Prince of Health

Much is hidden from us, of course, and many crafty devices escape our ken. Yet there is an answer we ourselves can deliver as we wait in hope for the judgment and the salvation of God. We deliver it when we defy their exercises in lordless power; when, heedless of their seductions and threats, we put our trust in God; when we seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, confident that our needs are known to God even before they are known to us.31 We deliver it when we refuse to regard as real what is merely illusion or to behave, for the sake of a false peace, as if the illusion were not an illusion. We deliver the answer, in its most incisive and potent form, whenever we confess with joy Jesus as Lord.

For the Lord Christ, as Augustine says, is the principium by which we are restored to health. “Having assumed soul and flesh, he cleanses the soul and the flesh of those who believe.”32 From which it follows that the true public health revolution, though some of our own pastors and doctors seem no longer to know it, is the revolution of the font. It is the mirifica commutatio or wonderful exchange by which, having taken what is ours, he gives us what is his.33 And what is his he has from the Father with an everlasting dominion. He has become both the principle and the Prince of a kingdom in which whole men are wholly present to God in a wholly pleasing way. He is the very Sacrament of a kingdom of health, of happiness, of security in happiness.

The ruins of the baptistry at Hippo Regius testify to the transitory nature of the kingdoms of this world, but every baptistry testifies to the Kingdom that is not transitory.

It is the burden of The City of God’s final book to speak of that kingdom. What a contrast it makes with the opening books, in which the acedia of the decaying Western empire is so poignantly described!

There, at the beginning of his magnum opus, Augustine takes to task those plutocrats who do not trouble themselves with the empire’s morality or spiritual well-being. The words he puts in their mouth, words that indict the poor as well as the rich, he might just as easily put in the mouths of their counterparts today:

“As long as it stands,” they say, “as long as it flourishes, rich in its resources and glorious in its victories, or—better yet—secure in its peace, what has any of that to do with us? Our concern is rather for each of us to get richer all the time. It is wealth that sustains daily extravagance. It is through wealth that the powerful subject the weak to themselves. Let the poor fawn on the rich for the sake of filling their bellies and in order to enjoy a life of laziness under their patronage. Let the rich make ill use of the poor to gain clients for themselves and to feed their own arrogance. Let the people applaud not those who look out for their benefit but those who provide for their pleasure. Let nothing harsh be commanded and nothing shameful be prohibited. Let kings care only that their subjects are docile, not that they are good.”34

Such was their doctrine of “sustainability.” Ours is little different. It is still a case of the rich making ill use of the poor. It is again the fatal disease of acedia. For nothing is sustainable that does not rest on God and on godliness; flourishing has no other foundation.35

But here, in the final book, all acedia is banished. Everything rings with newness, even Augustine’s rhetoric. As he prepares for his most daunting task—to speak of the palingenesia, in which what God accomplished in the resurrection of Jesus will come to fruition in the healing of the whole creation—he pauses over several miracles of healing in the name of Jesus. Not only miracles recorded in scripture, but miracles he himself had witnessed or of which he had reliable accounts.

Among the most moving of these are the ones that took place at Easter (c. AD 425) in his own cathedral, at the shrine to the protomartyr, Saint Stephen. Paulus and Palladia, two of ten siblings from a prominent family who had been cursed by their mother, made their way to Hippo manifesting “the horrible trembling of their limbs” that had beset them.36 They fled to that refuge to pray that God might “restore their former health.” Which God did, though I leave the reader to consult Augustine for details. Then, he says, the whole place rang with newness and with shouts of joy:

“Thanks be to God! Praise be to God!” No one was silent; the cries came from all sides… And what was in the hearts of these exulting people but the very faith in Christ for which Stephen’s blood had been shed?” 37

Thus does our guide bring us full circle to the shrines of the martyrs. As in Rome, so in Hippo; there is refuge to be found there against the deadly scourges that beset man. On this occasion, however, the cries to be heard on all sides are not the cries of the terrified, sheltering from Alaric’s marauding horde, but the cries of the overjoyed, who have witnessed a sign of the power of the Prince of Health and tasted the firstfruits of his revolution.

Ss Cosmas and Damian, standing before that Prince with their martyrial crowns, in the company of Peter and Paul. This church on the Sacra Via was repurposed from its imperial use and dedicated by Pope Felix IV in AD 526.

Augustine, like those patron saints of medicine, Cosmas and Damian, is certainly for medicine, not against it. His other stories make that clear. But he is firmly against medicine that fancies itself the Prince of Health. That is the kind of medicine we know today, the kind that belongs to a “new world order” that twenty-two years ago entered an ominous new phase of construction.

From the beginning of Desiring a Better Country, as of the present series attempting an Augustinian response to the Public Health revolution, it has been my burden to show that the principle of the one revolution and the principle of the other are in conflict, that the one order and the other are utterly incompatible. My readers, I expect, have long since settled their own view on that. So permit me to conclude with advice drawn from the lections appointed for today’s somber commemoration:

“Trust in him at all times, O people; pour out your heart before him; God is a refuge for us.” 38

And with a prayer, or rather with requests for prayer, on their behalf and mine.

Saints Cosmas and Damian, who delivered an answer in the days of Diocletian, pray for us. Saint Augustine, whose counsel we have sought, pray for us. Mother Mary, to whom we fly from Our Lady of Public Health, pray for us.

For example: From nature’s two sexes, between which one does not choose, scores of genders have been constructed to create the illusion of choice. This not only disorients; it dissolves respect for what Augustine (Civ. 22.24) refers to as propagation and conformation. Propagation is the capacity for bearing fruit and multiplying; conformation is the capacity to retain the goods proper to the nature that is propagating. The Public Health revolution despises both. In its earlier phase, as the sexual revolution, its first step away was the contraceptive step, from which followed the decline of the natural family and of traditional authority structures. The next step was same-sex marriage, which destroyed the natural family in principle even as it foundered in practice. The third step was the invention of gender as a replacement for sex—absurdly said to be “assigned at birth” by parents and doctors. The fourth was the weakening of whole nations through heavy-handed promotion of “gender mainstreaming” and “reproductive health.” Digital identities that actually are assigned at birth will help complete the process of subjugation, making the final step seem more feasible: the transhumanist step, the step into the clouds where all will be subject to those who ride the clouds. I have traced much of this in The Measure of the Beast.

Creatures have nothing with which to work other than what God has provided or promised to provide. In their own providence they are imitative. If they do not receive what God provides, they do not (and cannot) generate something else but only pervert what is already there by the application of dark arts. What is the Great Reset, for example, if not (as my pastor pointed out) an orcish imitation of what Jesus referred to as the palingenesia or renewal of all things?

The outcome of the trial of Tamara Lich and Chris Barber, Freedom Convoy organizers, currently taking place, we do not yet know. We must find ways to stand with them and perpetuate their work whatever the outcome.

See Civ. 11.21–24 (quoted from the Babcock translation, as elsewhere in this essay). The three questions correspond loosely to the three branches of philosophy: physics, logic, and ethics; or the natural, the rational, and the moral.

Civ. 19.13 (trans. mine)

John 1:14; cf. Exod. 40 and Rev. 7:15–17.

cf. 1 Cor. 2:6–13, 15:42ff., Rom. 8:18ff., and 1 John 3:2.

Civ. 22.30; cf. Irenaeus, at Haer. 4.6 and, famously, 4.20.7: “For the glory of God is a living man, and the life of man consists in beholding God.” Behind these patristic claims lie biblical texts such as 2 Cor. 3:18: “We all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another.”

Phil. 2:5–11. Our own path to glory is signposted just here as the path of humility. “Have this mind in you, which was also in Christ Jesus.”

See Psalm 139, which resounds in Civ. 22.24.

Though they attempt that today, not by praising the soul but rather by eliding any consideration of the soul, still they blame the flesh and so blame also the God who made man to be man. Augustine’s critique still stands:

With regard to our sins and vices, then, there is no reason to insult the creator by putting the blame on the nature of the flesh, which in fact is good in its kind and in its order. But it is not good to forsake the good creator and live according to a created good, whether one chooses to live according to the flesh, or according to the soul, or according to the whole man, who consists of soul and flesh and can, as a consequence, be signified either by ‘soul’ alone or by ‘flesh’ alone. For anyone who praises the nature of the soul as the highest good and blames the nature of the flesh as something evil is undoubtedly fleshly in both his attraction to the soul and his flight from the flesh, since his view is based on human folly rather than divine truth. (Civ. 14.5; cf. 10.24)

Article 2 of the Barmen Declaration, at 8.14-15. Put more dramatically by Tolkien, it is the answer made by Gandalf to the Balrog: “You shall not pass!” For what God in Christ has justified, and in the Spirit sanctified, belongs to God and not to the enemies of God.

I have explained this in The Secret of the Saeculum.

See further Desiring a Better Country (2015), chapters 1 and 5; cf. Leo XIII, Tametsi futura prospicientibus (1900) §13.

See Heb. 9:27f.; cf. 1 Thess. 1–2.

“And if you be unwilling to serve the Lord, choose this day whom you will serve, whether the gods your fathers served in the region beyond the River, or the gods of the Amorites in whose land you dwell; but as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord” (Josh. 24:15).

Happiness is not simply having everything you want, but "having everything you want and wanting nothing wrongly" (Trin. 13.8f.).

To enjoy the immutable good that is God himself, and to know that one will always enjoy him, is the only way to be happy, argues Augustine. The problem with paganism, committed as it is to a doctrine of eternal recurrence, is that this “always” is not on offer (cf. Civ. 11.13 and book 12). For who can be happy without having what he truly wants? And who does not want to keep what he wants, to retain what makes him happy? What happy person could wish to be unhappy again? If the best of the pagan philosophers—who dreamt in vain of the happiness of the soul and did not even dare to dream of the happiness of the whole man, body and soul—could not meet this challenge, how much less can their counterparts today, whose idea of the soul has degraded beyond recognition? They can dream only of the immortality of data, of a permanent record of the lives of those who once fancied themselves “souls.” But no one, however degraded their own soul, could confuse that prospect with happiness.

Trin. 13.13 (trans. Edmund Hill)

“God also made man himself upright, with the same freedom of choice—an animal of the earth, to be sure, but worthy of heaven if he clung to his creator.” Even after transgression, “he did not take away man’s power of free choice, for he foresaw at the same time what good he would himself bring out of man’s evil” (Civ. 22.1).

They may have both numbers and names, of course, but once numbered their capacity for meaningful choices has been severely restricted. Thus is repeated, on a global scale, the grave sin that occurred when “Satan stood up against Israel and incited David to number Israel” (1 Chron. 21:1; cf. 2 Sam. 24). That was a sin more severely punished than David's adultery, for the latter broke the law of God while the former put him in the very place of God. We are told that David “lifted up his eyes and saw the angel of the LORD standing between earth and heaven, and in his hand a drawn sword stretched out over Jerusalem” (21:16). This, let the reader understand, is the image taken up in Revelation 10. I will say more about that another time.

See Civ. 4.32. Augustine is speaking of Roman civic religion; ours is different in many ways, yet in character, process, and results it is much the same.

See Sir. 42:15ff.

See Civ. 21.15 (cf. Calvin, Inst. 4.17.2):

For there is only one Son of God by nature, and he in his compassion became a son of man for our sake so that we, who are by nature sons of man, might by grace become sons of God through him. Remaining immutable in himself, he took our nature on himself so that, in our nature, he might take us to himself. Holding fast to his own divinity, he participated in our infirmity so that we, changed for the better, might lose our condition of sin and mortality by participating in his immortality and righteousness and might preserve the good he accomplished in our nature, perfected by the supreme good in the goodness of his nature.

The First Vespers of the Purification references more briefly this admirabile commercium: “O admirable Interchange! The Creator of mankind, assuming a living Body, deigned to be born of a Virgin; and becoming Man, without man’s aid, bestowed on us his Divinity.”

Civ. 2.20

Thankfully, even the rich and rapacious cannot take godliness from those who will to be godly; for “in the holy and supernal city … God himself is the reality by which they are sustained and made blessed” (Civ. 22.1).

To the best of my knowledge, they had not been subjected to any gene therapy treatment under the curse of Our Lady of Public Health, though that, we discover, can have the same effect. Our cure is to call it an FND.

Civ. 22.8. The expression “rings with newness” I have borrowed from Babcock at 16.26. The martyrdom of Stephen is recorded in Acts 7. Reference to “the renewal of all things, when the Son of man shall sit on the throne of glory,” is at Matt. 19:28, an exposition of which is provided in the final two chapters of the Apocalypse.

Attention has been drawn to this: https://www.un.org/pga/77/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2023/08/Final-text-for-silence-procedure-PPPR-Political-Declaration.pdf

And today a friend in NZ sent this: https://www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/27180-new-zealands-future-quarantine-and-isolation-capability-proactiverelease-pdf

Reckoning with this sort of thing can of course be fear-inducing. What I have written above is intended as an antidote to fear.

Just getting started?

https://dailysceptic.org/2023/12/14/the-sinister-public-health-agenda-is-just-getting-started/