The Dragon and the Beast from the Sea (C14 French tapestry)

In §28 of Laudate deum, Francis issues a word of warning to the world “on the climate crisis,” couched in apocalyptic terms:

We need to rethink among other things the question of human power, its meaning and its limits. For our power has frenetically increased in a few decades. We have made impressive and awesome technological advances, and we have not realized that at the same time we have turned into highly dangerous beings, capable of threatening the lives of many beings and our own survival. Today it is worth repeating the ironic comment of Solovyov about an “age which was so advanced as to be actually the last one.” We need lucidity and honesty in order to recognize in time that our power and the progress we are producing are turning against us.

Francis released his Apostolic Exhortation on the eve of the Synod on Synodality, which has just concluded its first phase. The synod is also about "the meaning and limits of power: papal power, episcopal power, lay power. And I do mean power, not authority. Authority leads to dogma. Only on the grounds of authority can dogma be dogma or be received as dogma. But attention to dogma, we have been told, encourages rigidity, if not frigidity. The goal of the synod is to turn the Catholic Church into a sort of procedural republic, of the kind familiar from Anglican and Protestant spheres. It will be a fellowship of listeners and a communion of communiqués. It will be a people who through “conversations in the Spirit” learn to find a word from God in each other's experiences. But they will still have to find ways to distribute power, or ways will be found for them.

The name of Jesus appears in this Exhortation only three times: twice at the beginning, to tell us that he was sensitive and tender; once near the end, to tell us that he invited others to attend to the beauty of nature. He was the very model, in other words, of one who listens to nature and to his fellow humans. Only as such, it seems, is he the answer to the alleged “crisis,” a word that appears ten times. Or of “global” relevance, a word that appears some thirty times. His own power lies altogether in his sensitivity. So the Exhortation is as germane to the Synod on Synodality as to the climate crisis. Arguably the whole synodal process, the prototype of which ran in Germany as Der Synodale Weg, is a decadent Catholic version of what Schleiermacher called for at the end of his fifth speech on religion: “To worship the God that is in you, do not refuse us.” In a curiously inverted fashion, however, this three-year exercise in navel-gazing also answers to the final lines of the epilogue to the Speeches, fulfilling Schleiermacher’s prophecy respecting those who still insist on being Catholic after the great Illumination: “They will rush into a vain and fruitless activity, and the portion of art that God has lent them will turn to foolishness.”

October 2023

In this context, the pope’s appeal to Solovyov appears painfully dislocated, like a shoulder out of joint. It was on the eve of his death that Solovyov wrote the book from which Francis quotes. In it, he makes a prophecy of his own. Solovyov prophesies that a false church will betray the true, but, in betraying it, also reveal it as true. Only thus will the latter at last be granted that peace and unity which is in accord with God's will. The former, on the other hand, he expounds as the product of an apostate generation that thinks it can dispense with truth, beginning with dogmatic truth. It is to a crisis of truth—the truth of the faith and especially of resurrection faith—that he points, and it is the tendency to see dogma as rigidity against which he warns. olovyov lampoons the false church already in the preface to his book. It is vain and fruitless in the extreme, for at its heart is no gospel but only a hole where the gospel ought to be.

Like Francis, Solovyov directs a question to evolutionary optimists and their cult of progress. It is not a question about the dangers inherent in man's technological prowess, however, but a question about man himself and his religion. More specifically, it is a question about whether we should regard evil as “only a natural defect, an imperfection disappearing of itself with the growth of good,” or reckon with it as “a real power, possessing our world by means of temptations.” If the latter, then help in fighting it, insists Solovyov, “must be found in another sphere of being” altogether. Mere political manoeuvring, such as Francis proposes—we will come to that in a moment—or “listening” drills, such as were used at the synod, will avail nothing. What is really required is Jesus Christ himself.

This is not what we hear in Laudate deum. In its final line, Francis does warn technocratic man against presuming to take God’s place as conductor of the “marvelous concert” of all God’s creatures. Such a man, he says, becomes his own worst enemy. For “the technocratic paradigm can isolate us from the world that surrounds us and deceive us by making us forget that the entire world is a contact zone” with God (§66). To this warning even the dogmatically rigid might manage an amen. But note: these words, “contact zone,” are drawn from a passage in Laudato 'Si (§233) where he leans on the Sufic spiritualist, Ali al-Khawas, who “stresses from his own experience the need not to put too much distance between the creatures of the world and the interior experience of God.” Francis displays here his tendency to think outside the confines of the creed; even to tug at the pantheistic strands of Western mysticism, from Eckhart to Teilhard, which also invite one to go in search of the God within us, or at least of that “narrow gate in the depth of the soul,” as Martin Lings puts it, “through which it can strike out into the domain of the pure arid unimprisonable Spirit which itself opens out on to the Divinity.” For this, Jesus Christ, however inspired, is not required. He may even be an impediment.

Just so, Francis puts himself alongside the earlier rather than the later Solovyov, who in War, Progress, and the End of History offered an urgent corrective to all this. Solovyov saw, belatedly, where the mystical spirit, whether Sufic or Sophian or even Jesuit, was leading. It was leading to hard, cold, totalizing politics. To a global council with a global rationalization for a global tyranny. Francis, if he worries about that, doesn’t worry very hard, apparently. Combining his own brand of nature mysticism (I do not think it that of St Francis) with a commitment to anthropogenic global warming catastrophism, he proffers as a solution the creation of a global climate authority with teeth. This, of course, is the very solution his new advisors, such as the Guardians for Inclusive Capitalism, are urging, if rather less mystically.

Solovyov would be deeply suspicious. Here are a few passages excerpted from what he actually wrote, beginning with a remark on the passing of rationalistic materialism into something vaguely mystical and anti-dogmatic, something in which neither faith nor reason is fully operative. He is looking ahead to the twenty-first century:

Humanity had outgrown that stage of philosophical infancy. On the other hand, it became equally evident that it had also outgrown the infantile capacity for naive, unconscious faith. Such ideas as God creating the universe out of nothing were no longer taught even in elementary schools. A certain high level of ideas concerning such subjects had been evolved, and no dogmatism could risk a descent below it. And though the majority of thinking people had remained faithless, the few believers, of necessity, had become thinking, thus fulfilling the commandment of the Apostle: “Be infants in your hearts, but not in your reason.”

In such a context, where so few combine simple faith with powerful reason, pseudo-solutions to real or imagined problems are put forward with religious enthusiasm:

Absolute individualism stood side by side with an ardent zeal for the common good, and the highest idealism in guiding principles combined smoothly with a perfect definiteness in practical solutions for the necessities of life. And all this was blended and cemented with such artistic genius that every thinker and every man of action, however one-sided he might have been, could easily view and accept the whole from his particular individual standpoint without sacrificing anything to the truth itself, without actually rising above his ego, without in reality renouncing his one-sidedness, without correcting the inadequacy of his views and wishes, and without making up their deficiencies.

Put forward by whom? By powerful men who have taken control of the United States of Europe and are seeking to achieve something like the structures for which Francis now appears to be calling. These men, however, are not men of faith, unless Freemasonry can be called a faith, which no doubt it can.

The “initiated” then decided to establish a one-man executive power endowed with some considerable authority. The principal candidate was the secret member of the Order—“the Coming Man.” He was the only man with a great worldwide fame. Being by profession a learned artilleryman, and by his source of income a rich capitalist, he was on friendly terms with many in financial and military circles. In another, less enlightened time, there might have been held against him the fact of his extremely obscure origin. His mother, a lady of doubtful reputation, was very well known in both hemispheres, but the number of people who had grounds to consider him as their son was rather too great. These circumstances, however, could not carry any weight with an age that was so advanced as to be actually the last. “The Coming Man” was almost unanimously elected president of the United States of Europe for life.

So there's that phrase that Francis quotes, about an era or society so advanced as actually to be the last. It is an ironic phrase, but Solovyov's irony is not Francis’s irony. He is not referencing our astonishing technological prowess, which we lack the wisdom to deploy safely. He is referencing rather the fact that our society, having outgrown the old dogmas about God, creation and fall, incarnation and redemption, has outgrown truth altogether. It has become so "advanced" that it no longer needs it. What does it need? It needs only peace. And since it doesn't really believe either in God or in evil, it thinks it can have peace by political reconfiguration. It needs global governance, in other words, hence also a global government. This requires a governor, whose parousia Solovyov goes on to narrate.

But peace, if real, must be good and just. The war against evil and injustice must be won before peace can prevail. What peace requires, then, Solovyov insists, is Christ himself. Anyone else can only be antichrist, the man who takes the place both of God and of his Christ: the last man, in the last generation of man, the generation on whom final judgment is to fall.

Now, Francis isn't calling for antichrist. He is not even calling for global governance. He is merely calling for a new and different multilateralism with the authority to whip climate-change deniers and environmental abusers into shape. “It is not helpful,” he says at §35,

to confuse multilateralism with a world authority concentrated in one person or in an elite with excessive power: “When we talk about the possibility of some form of world authority regulated by law, we need not necessarily think of a personal authority.” We are speaking above all of “more effective world organizations, equipped with the power to provide for the global common good, the elimination of hunger and poverty and the sure defence of fundamental human rights.” The issue is that they must be endowed with real authority, in such a way as to “provide for” the attainment of certain essential goals. In this way, there could come about a multilateralism that is not dependent on changing political conditions or the interests of a certain few, and possesses a stable efficacy.

Francis is, as usual, quoting himself, something popes do even more than the rest of us. Sounding for all the world like Klaus Schwab, however, he adds:

It continues to be regrettable that global crises are being squandered when they could be the occasions to bring about beneficial changes. This is what happened in the 2007-2008 financial crisis and again in the Covid-19 crisis. For “the actual strategies developed worldwide in the wake of [those crises] fostered greater individualism, less integration and increased freedom for the truly powerful, who always find a way to escape unscathed.”

The real challenge, he posits in the following paragraph, is not to save the old multilateralism, meaning the multilateralism of nation-states, but rather “to reconfigure and recreate it, taking into account the new world situation” (§37). For this task, something like those public-private partnerships promoted by the World Economic Forum would be useful, though Francis does not mention the WEF or its founder or 3P arrangements by name. He prefers to speak only of a “global-local arrangement” to which the principle of subsidiarity and other staples of Catholic social thought can be applied:

38. In the medium-term, globalization favours spontaneous cultural interchanges, greater mutual knowledge and processes of integration of peoples, which end up provoking a multilateralism “from below” and not simply one determined by the elites of power. The demands that rise up from below throughout the world, where activists from very different countries help and support one another, can end up pressuring the sources of power. It is to be hoped that this will happen with respect to the climate crisis. For this reason, I reiterate that “unless citizens control political power—national, regional and municipal—it will not be possible to control damage to the environment.”

39. Postmodern culture has generated a new sensitivity towards the more vulnerable and less powerful. This is connected with my insistence in the Encyclical Letter Fratelli Tutti on the primacy of the human person and the defence of his or her dignity beyond every circumstance. It is another way of encouraging multilateralism for the sake of resolving the real problems of humanity, securing before all else respect for the dignity of persons, in such a way that ethics will prevail over local or contingent interests.

It is an excellent thing, a magisterial thing, to work together with secular authorities to introduce or reintroduce Catholic principles into proposed modes of political or social action; to leaven laws and treaties and partnerships and policies with reminders of natural and divine law. But it is not clear here which is doing the leavening. Natural and divine law don’t seem much in evidence, just as Christ is not much in evidence. Even natural science is present in name only.

Francis, who began his pontificate on an already problematic environmentalist note—not that sounding such a note is problematic, but the note itself is problematic—thinks climate science settled, and settled in favour of the Greta Thunberg school of apocalyptic alarmism. It being no part of his magisterial function to deliver such judgments, however, it is no part of the religious assent (obsequium religiosum) of the faithful to submit to them. A case can be made, and must be made in the charity of truth, that he is mistaken, mistaken even to think in terms of “settled” science.

Climate-change apocalypticism didn't arise from science, in fact, but rather from Malthusian errors and from men who quickly grasped that all such putative crises—population crises, climate crises, health crises, economic crises—could be put to good use in putting men from their own circles in charge of just about everyone else. Such men are not given to upholding the principle of subsidiarity. Indeed, as I have argued, they have put it fully into reverse.

But let us return to the paragraph with which we began. What is said there, at Laudate §28, does fall within the magisterial function. It warrants careful pondering, by those people of good will to whom this Exhortation is directed, and by all the faithful. Read with Solovyov, rather than against him, it may even invite us to ponder something far more important to the future of mankind than the alleged climate crisis—something Solovyov was pondering with the help of St John. And now we may turn to St John.

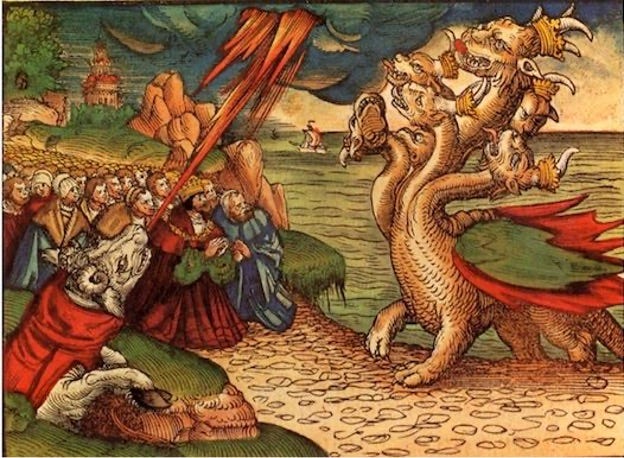

Illustration from the Luther Bible, showing both beasts, per Revelation 13.

The Apocalypse begins with a revelation to John of the power and authority of Jesus Christ, who holds the keys to life and death, who unlocks the secrets of history, who determines the fate of the world and of the churches. Its thirteenth chapter asks us, as Francis does, to face “the question of human power, its meaning and its limits.” Indeed, it asks us to contrast the power and authority of Jesus with the antichristic potential of human power insofar as its meaning and limits are ignored. It asks us to recognize that human power, in defection from the divine source of all power and authority, is susceptible to manipulation and expropriation by the Evil One, here pictured as a dragon or leviathan.

I saw a beast rising out of the sea, with ten horns and seven heads, with ten diadems upon its horns and a blasphemous name upon its heads... And to it the dragon gave his power and his throne and great authority... Authority was given it over every tribe and people and tongue and nation, and all who dwell on earth will worship it, every one whose name has not been written before the foundation of the world in the book of life of the Lamb that was slain.

This is a prophecy that mankind, forgetting that all true authority comes from God and remains with God, will eventually mistake false authority for true. True authority occurs, as Augustine says, when justice accedes to power. Power without justice is not true authority and must resort to deceit and coercion. To justify itself, it has ultimately to do just what John (following Daniel) describes. It must “utter blasphemies against God, blaspheming his name and his dwelling.” It must “make war on the saints,” so as to conquer them. And God will permit this, both to test and glorify the faithful and to bring the wicked into judgment—catastrophic judgment that will put an end to perverse power and authority once and for all.

All this Solovyov understood. That is why he spoke of the approach of the end, and of the last generation as a generation in thrall to a false authority, to a Christ substitute. According to Francis, “when we talk about the possibility of some form of world authority regulated by law, we need not necessarily think of a personal authority.” That is true enough, perhaps, “in the medium term.” But in the last analysis we can and should think, as the prophets and apostles think, in terms both of a system and of a person; that is, in terms of an authority that is personal. For all authority is ultimately personal, since (if real) it stems from the person of the Father, who has vested it in his Son: “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me,” declares the risen Jesus. One must look for it just there or, if not there, then in an antichrist, at once corporate and personal. Impersonal authority is an illusion.

That, too, is something Solovyov understood, as you will see if you read his whole book, with its famous concluding chapter, A Short Tale of the Antichrist. As with any good book, the final chapter cannot be read properly without reading the whole book. And what more poignant moment in which to read it than the present moment? If its first chapter, on war, which gazes unblinkingly at the appalling evil men are capable of, doesn't speak with authority to the situation in which we once again find ourselves in the Middle East, I don't know what does. Both the atrocities of Hamas and the facilitating decay of Western culture begin to appear in their true light when that chapter is examined. The next two chapters, which debunk the myth of progress by facing us with the question of our own death, prepare us for the final chapter's treatment of the failure of the churches to recognize what is really happening in our world.

What is really happening is not climate change, unless by “climate change” we mean that the beast rising from the earth is joining forces with the beast rising from the sea. For Solovyov knew very well that the Apocalypse speaks, not of one beast, but of two:

Then I saw another beast which rose out of the earth; it had two horns like a lamb and it spoke like a dragon. It exercises all the authority of the first beast in its presence, and makes the earth and its inhabitants worship the first beast, whose mortal wound was healed. It works great signs, even making fire come down from heaven to earth in the sight of men; and by the signs which it is allowed to work in the presence of the beast, it deceives those who dwell on earth, bidding them make an image for the beast which was wounded by the sword and yet lived; and it was allowed to give breath to the image of the beast so that the image of the beast should even speak, and to cause those who would not worship the image of the beast to be slain.

This second beast, like the first, is both system and person. In both respects, it is dubbed by John (following Jesus) “the false prophet.”

We need here a dose of eschatological realism. At Rev. 16:13, John writes of three demonic spirits, performing false signs and wonders, that issue like frogs “from the mouth of the dragon and from the mouth of the beast and from the mouth of the false prophet,” respectively, spirits that “go abroad to the kings of the whole world, to assemble them for battle on the great day of God the Almighty.” (Psalm 2 stands in the background here, together with Joel 3:14–16, and Zech. 14; see also Exodus 8.) It may be tempting to think that figures such as the dragon, beast, and false prophet are only personifications, not persons, but that is a mistake. The dragon is Satan. The first beast, besides being a world economic and political order, is the man of sin who heads that order. The second beast, besides being a world religion of some sort, is the false prophet who is its chief pastor. The kings who take counsel together, against the Lord and his Anointed, are likewise real persons, and so is the Rider on the White Horse, who will come with his holy angels to do battle with them all.

Battle has already been struck, of course, many times and in many places. That is characteristic of the age, which by reason of the announcement of the authority granted to God’s Christ becomes a field of contest with other claimants (Matthew 24). But this does not mean that battle will not be struck in definitive form at the end of the age. Quite the contrary. What does not yet appear, except in apocalyptic visions, as definitive and final will eventually appear as definitive and final. The mystery of lawlessness that is already at work will resolve into the man of lawlessness. The destinies of those involved in the struggle will then be settled publicly, as Paul declares in 2 Thessalonians 2. Meanwhile a deceiving influence will go forth, issuing from the mouth of the dragon and the beast and the false prophet.

This dialectic, referencing two beastly systems, each with many representatives but also one final representative, we find at work in 1 John 2 as well, as indeed in that whole epistle. In history's last hour—the present age—there are already antichrists and there will, in due course, be the antichrist. There are already false prophets, who bear the spirit of antichrist (1 John 4:3), and there will be, in his time, the false prophet par excellence. There is also the Evil One, with his demonic subordinates. He stands throughout as the fons et principium of this unholy trinity (1 John 5:19), with its seductive simulacrum of authority that is, at bottom, nothing but raw and rapacious rage.

As for the systems within which the antichrist and the false prophet will operate, building on those who went before them, we may say that the chief characteristics of the one beast are deception and coercion; and of the other, ambiguity and syncretism. In the case of the latter, the beast from the earth, that means rejection of any fixed doctrine over which men might divide, division being the only evil against which it is deemed necessary to do battle. Which will also come to coercion, of course, for coercion (Arendt is right) begins where genuine authority leaves off.

Alas, one does not have to seek far for signs of ambiguity and syncretism even in the present pontificate, as is often remarked. But of course I do not endorse the view, evident in the above Lutherbibel illustration, that the papacy itself is the form of the false prophet. (If you’d like an endorsement for that, you might ask Schleiermacher.) Let’s take a closer look at both beasts.

William Blake, the Number of the Beast; that is, of the false trinity.

Just as the gospel is for the Jew first, but equally for the Greek, so also is rejection of the gospel. Reception redeems and reorders, rejection disorders; yet even the disorder is newly ordered in a perverse way. Thus arises a beast, and not one beast but two. (A “beast,” in this context, is not a creature of God, good in itself though lacking the good of rationality that distinguishes man from other animals; it is rather a creation of man, when what is good is deprived of the goodness proper to it.) The beast from the sea is the beast that arises from the Gentiles, from multilateral minglings among the nations, which seek but cannot find true cohesion. It is the form “authority” takes when power precedes and perverts justice, rather than following from justice.

In John's day, that beast was the Roman Empire, under those Caesars who did not acknowledge Christ and who put his followers to the sword. It was dealt a mighty blow by the much sharper sword of the Word of God. Its head was struck even as it lacerated the Church's heel, for the blood of the martyrs became the seed from which the Church itself grew. But the beast from the sea is hydra-headed. It has recovered from its mortal wound and is beginning to mouth blasphemies against Heaven such as it had never even thought of before, though it had already thought for some time. Today it is finding new ways “to make war on the saints and to conquer them.” Beware the beast from the sea! But beware also, and especially, the beast from the earth.

The beast from the earth is the beast that arises from among the covenant people; first from the Jew, then from the Greek. For the man who worships God, who receives all the goodness created by God with the thankfulness due God, who also fears and obeys God, fulfilling the debt of love, is the man who stands on solid ground within the covenant and under its protection. It is possible, however, to betray the covenant and the mission appointed by God for the covenant people. It is possible to abandon land for sea. (One thinks of Jonah, who was sent by land to Nineveh, but took by sea for Tarshish.) It is possible to betray the Christ, even to the extent of inducing worship of the beast from the sea. (One thinks of Judas, the traitor, who knew the art of kissing.) As John presents it, the beast from the earth lends breath and voice to the beast from the sea, which lacks its refined lungs and vocal chords. It seeks to achieve the global religious synthesis for which its visionaries have always looked. The beast from the sea speaks with braying voice, loud but inarticulate. The beast from the earth speaks softly, sometimes even with the gentleness of the Lamb, yet the one who listens closely hears the words of the dragon, spoken with pious eloquence.

The beast from the earth “exercises all the authority of the first beast in its presence, and makes the earth and its inhabitants worship the first beast, whose mortal wound was healed.” It provides the nations with a sign of belonging to the first beast, a protective sign analogous to circumcision or baptism. It “causes all, both small and great, both rich and poor, both free and slave, to be marked on the right hand or the forehead, so that no one can buy or sell unless he has the mark; that is, the name of the beast or the number of its name.” And when it becomes necessary, it causes those who will not worship the first beast to be slain.

The beast from the earth is a parody of the Church, not the Church itself. But the role it plays cannot be played so long as the true Church is seen to stand over against it, as an alternative to it. That is why it persists in suborning members of the Church and insinuates itself as far as possible into the Church, taking a seat at the holy table, performing its parody inside as well as outside. It is determined to overcome the old catholicism with a new catholicism. Lately, it has even invented its own Mary, whom I call Our Lady of Public Health. Soon enough, it will reveal its own Christ, whom it would have us confuse with Jesus. Perhaps only the last-minute conversion of Jews, kin to Mary and Jesus, will prevent most Christians from going over to its false Christ. (That seems to be what St Thomas thought, when commenting on Romans 9–11.)

The beast from the sea, we have said, is a perverse world order before it is a particular world leader. The beast from the earth is a perverse religious system, which prostitutes the goods of the covenant in support of that order, which is the whole business of false prophets. Thus does it cause the beast from the sea to be admired even by those who ought to know better. John tells us that this calls for true wisdom. For the beast from the earth is even slippier and trickier than the beast from the sea, whose mark it persuades men to receive. He adds, enigmatically, “Let him who has understanding reckon the number of the beast, for it is a human number; its number is six hundred sixty six.”

Now, Augustine proposed that we read such passages metaphorically rather than literally. That approach recommended itself, not only because the Apocalypse is full of images and metaphors, constructed through allusions to earlier scriptures, and cannot on the whole be read literally; but also because Augustine took the opening of Revelation 20 to refer to the entire age between the advents of Jesus:

I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded for their testimony to Jesus and for the word of God, and who had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life, and reigned with Christ a thousand years.

“They do not worship,” he opines, “means that they do not consent or submit; and they do not receive its mark, which is a sign of guilt, either on their foreheads, by reason of what they profess, or on their hands, by reason of what they do.” They compromise neither faith nor morals, in other words. They do not say what they know to be false and they do not do what they know to be wrong. They reign with Christ because they are “the people who are strangers to such evils.”

All of which makes excellent sense. Perhaps it is enough to go on. It does not preclude, however, a more literal rendering, pointing to an actual mark, visible to the beast’s technology though not to the naked eye. The literal need not compete with the metaphorical or undermine it. We might think of this mark as the signum proper to the res, the sign proper to the reality. We might see its bestowal as performative, just as washing with water is performative in the sacrament of baptism, through which the conscience is cleansed by the remitting of sins. But the mark or sign here is a sign of guilt, not of innocence. It is a counter-sacrament that serves as a deed of possession, of belonging to the twin beasts that belong to the dragon. And this counter-sacrament will be blessed by apostasizing elders, who will cast down their crowns before the wrong throne. No doubt they will justify that by claiming that what the beast from the sea demands, if demanded by law or statute, the beast from the sea should get; for its demands are essentially “secular” and it is the duty of the faithful to defer in secular matters to secular authorities.

I have spoken to this justification elsewhere, including an article soon to appear in Touchstone. What I want to say here is that we have reasons Augustine did not have for holding together (as he often does) the literal and the metaphorical. We know that such a mark is possible, because of technological advances. We know that it is desired and intended. We are, some say, well down the path toward mandatory digital identities and subcutaneous tagging as a condition for buying and selling or accessing public services. How’s that for global authority with teeth?

John identifies the beast from the sea only by reference to “the number of its name.” This has often been understood as code for this or that Caesar or some Caesar yet to come. Fair enough, though easily abused. But it is more important to observe that the beast, viewed as system, is numerical by nature. Does baptism confer a new identity? So does the beast; only the new identity it confers is digital, not personal. As such it is a secret of sorts, but not a secret name, known only to Christ and the one who receives it (cf. Rev. 2:17 and 3:12). It is a number in place of a name. It generates not a new man but a new cog in the Machine.

How then is the beastly number a human number? It is a human number in an inhuman sense. It is assigned to the man whose entire hope is in temporal health and safety, in secular peace and security, in worldly goods—to the man who no longer seeks salvation of soul and who is therefore without prospect of entering the divine rest. It is assigned by those who think it possible to remain in the sixth day of creation, having “dominion over every living thing that moves on the face of the earth,” while refusing the seventh, in which all is offered back to God with thanksgiving, with reciprocal rejoicing. It is the number, not of exponential gains—eucharistic gains, through communion with that God who made the sabbath for man, not man for the sabbath—but rather of exponential losses, of diminishing returns.

Six hundred, sixty, six. Even read as addition, it represents diminishing returns. Read as subtraction it is, as Augustine would say, a “veering towards nothingness.” This is the number of the man who thinks he must decline in order to advance, the man who must leave behind his humanity and embrace the transhuman on his way to the suprahuman. If only he meant to decline in hubris, so as to advance in humility, he would be on the right track! But he is not on the right track. His days are numbered. He shall come to nought.

That Word of Warning Again

He does not know that, of course. He is still busy laying plans for platforms that “will help the global community fulfill the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, which include requiring everyone—including infants—to have a digital identity by 2030 in order to work, vote, and access financial, social and medical services.” Truth be told, he is laying plans for far fewer infants and he is well down that path, too, the path that leads to a demographic winter in which even the Machine may have trouble functioning. What was it Jesus said about those days having to be shortened?

Francis may suppose that if we're to conjoin the literal and the metaphorical we might do better to focus on John's vision of a third of the earth being burned by fire, and to put this down to climate change. Well, suppose we did? That would not alter the fact that the new multilateralism for which he calls lends itself to that for which he does not call; viz., the kind of control, and a level of control, that was once believed to belong only to God but now threatens to put man in the place of God.

Man in the place of God—that is what Blake’s rendering of “the number of its name” suggests. The number of its name is three-in-one. It is the number of an unholy trinity, yet also a human number. Wherever man pretends to be God, he is a merely the puppet of Satan. He wields a scepter that is not his and pretends to a knowledge he does not have. In that sense he is Satan, his own adversary, his own worst enemy.

Asaph, sometime chief liturgist in Israel, knew and briefly envied that kind of man, the kind who sets his mouths against heaven and whose tongue struts the earth, persuading others that there is none like the beast and that none can hope to fight against it. Against his temptation Asaph sought refuge in the sanctuary of God, where he perceived the end of such men.

For lo, those who are far from thee shall perish;

thou dost put an end to those who are false to thee.

But for me it is good to be near God;

I have made the Lord God my refuge,

that I may tell of all thy works.

To be near God, to make the Lord God one's refuge, to seek him in his sanctuary: that is what the wise do. But they must do it with eyes and ears wide open. For Jesus and Paul and John all warned us that anomic man, the man of lawlessness, knows of this sanctuary; he is hard on Asaph's heels. He himself will go into the sanctuary and seat himself there. He will seat himself in the temple of God as if he were God.

When Augustine ponders this prospect, he is not quite certain what to make of it. Of what temple is Paul speaking? Is it the temple of the Jews, which still stood at the time, and might some day stand again? Or is it the temple that is the Church, which was already being raised up by the Holy Spirit? Or is it the temple of creation, where the man of lawlessness will reign over all men as Lord of the World? For present purposes we need not choose, though I have argued in my commentary on Thessalonians that the primary reference is to the Church. In Laudate deum and the Synod on Synodality, I find no reason to change my mind.

The course we are on is the wrong course. There are those who say that, because the Spirit has promised to guide the Church into all truth and the Petrine charism is sufficient to guard against collapse into untruth, we cannot possibly be on the wrong course. I accept their premises, but not their conclusion. They seem to me to lack either the lucidity or the honesty to recognize that, from these facts, a false confidence has been constructed. It is a dangerous confidence that does not rest squarely on the Church’s one foundation, which is Christ. I urge them to examine the scriptures and the catechism afresh, and to read Solovyov for themselves.

Apologies for comments having been closed; that was accidental, though the subject matter might suggest that it was on purpose!

What do you think about the fact that Francis recommends the following truth telling classics: "the betrothed" (tells truth about marriage and contemporary priests running away from pastoring same) and "Lord of the world" (apocalyptic anti anti Christ).