The Real Victory Over Evil

A sequel to "The Hole in Your Culture," with special attention to Solovyov

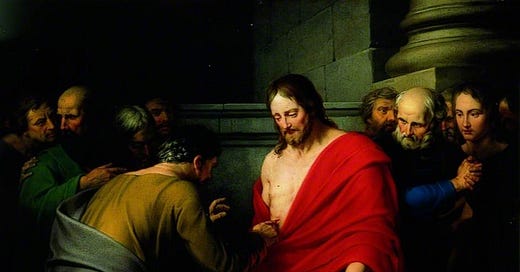

Benjamin West

St Thomas (John 20) is probing the spear-hole in the side of Jesus, after which he worships the Victor over death. For my initial remarks on Solovyov, who saw clearly what the alternative looked like, see here.

If we receive the testimony of men, the testimony of God is greater; for this is the testimony of God, which he has testified concerning his Son. — 1 John 5:9

The real victory over evil in the real resurrection. Only this, I repeat, opens the real Kingdom of God whereas, without it, you have only the kingdom of death and sin and their creator, the Devil. The resurrection, and not in its metaphorical, but in its literal meaning—here is the testimony of the true God. — Mr. Z., in Solovyov's War, Progress, and the End of History

Eastertide in both East and West. What better time to speak with Solovyov of that real victory over evil, the victory in which (so he worried) even many Christians do not really believe? Or to think further about what they are substituting for it, as they try to fill the hole in their culture where the sense of that victory used to be?

Let us speak about the real thing first, attending to the simulacrum second. Each will require consideration in two stages.

The Mutual Testimony of the Father and the Son

The resurrection of Jesus from the dead was, on one level, a legal affair. That is, it was the overruling of human judgment by divine judgment. On another level, it was a political and military affair. It was the victory of God over the devil, that rebel referred to in Christian lore as Lucifer, whose forces (demonic and human) were routed. On yet another level, it was a profoundly personal affair. It was the deliverance of a faithful Jewish man from the clutches of his enemies, including the enemy of every man, death.

On each of these levels, the resurrection has cosmic implications, as the New Testament makes clear. Take John 20, for example, which (like the book’s prologue) harks back to the first chapters of Genesis. With the resurrection of Jesus there comes a new creation. The swords of the cherubim are sheathed and the road to Eden is reopened. Right relations are restored. Here is a man who recognizes God, just as man ought to recognize God. Here is a woman who begins to recognize, without impeding, the man who recognizes her. Here is a community of men into whom the breath of life is breathed, that they might glory in the Lord and reflect that glory to the ends of the earth. Blessing flows, like the waters of Eden, in every direction.

There is a still more theological level, however, that we must not miss. It concerns the mutual testimony of the Father and the Son, the testimony on which the community of his disciples is wholly dependent: “All things have been delivered to me by my Father; and no one knows who the Son is except the Father, or who the Father is except the Son and any one to whom the Son chooses to reveal him” (Luke 10:22). This saying John undertakes to expound, with an intimate knowledge that seems to surpass that of the others. It is plain in all four Gospels, however, that just as the cross provides the ultimate testimony of the Son to the Father, so also the resurrection provides the ultimate testimony of the Father to the Son.

The whole narrative points us in that direction. It situates Jesus as the suffering servant. It places him alone in the lion's den and the fiery furnace. It puts him alongside the psalmist who, tormented by the wicked, cries out:

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning?

O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer;

and by night, but find no rest.

These are the very words Jesus takes up from the cross, carrying the act of petition even into the place where the covenant curses are being meted out, the Place of the Skull. He shares the psalmist's confidence in the one he is petitioning:

Yet you are holy,

enthroned on the praises of Israel.

In you our ancestors trusted;

they trusted, and you delivered them.

To you they cried, and were saved;

in you they trusted, and were not put to shame.

He too is heard and answered. He is vindicated by his Father, not merely by the centurion standing at the foot of his cross. He is taken down and buried, but he is "designated Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead" (Rom. 1:4) on the third day.

You who fear the Lord, praise him!

All you offspring of Jacob, glorify him;

stand in awe of him, all you offspring of Israel!

For he did not despise or abhor

the affliction of the afflicted;

he did not hide his face from me,

but heard when I cried to him.

So the good man is saved and evil men are put to shame. Even Death and Hades are put to shame, now that the curses of the covenant are exhausted. The faithful Son has borne witness on earth, and his faithful Father has replied from heaven. Both have given testimony, both have borne witness.

When the stone of unbelief is rolled away, permitting one to receive this mutual testimony, the recipient himself is changed. The divine testimony is internalized in him. Through the Son’s love, even unto death, he learns who the Father really is. And through the Father’s life, the eternal life the Father vests in the Son, he learns who the Son really is. This is the sphere of the Spirit who mediates, bearing witness both on earth and in heaven. It is the sphere of the liturgy, in which there is a reciprocal rejoicing between life as love (Good Friday) and love as life (Easter). It is also the sphere in which it is understood that there is a war between good and evil, the sphere in which good continues to do battle with evil, and with the help of the triune God to triumph over evil.

All this is elaborated in the final chapter of the first epistle of John, which eventually sends us back to the Lord's Prayer and its concluding petitions, so as to prepare us for battle:

Whatever is born of God overcomes the world; and this is the victory that overcomes the world, our faith... This is the confidence which we have in him, that if we ask anything according to his will he hears us... We know that anyone born of God does not sin, but He who was born of God keeps him, and the Evil One does not touch him. We know that we are of God, and the whole world is in the power of the Evil One.

And just here we may return to Solovyov, who took no small interest in this battle. His interest was at once theological, political, and existential, as ours will be.

The Necessity of War with Evil

The divine life of love is fecund, eternally fecund; hence just as capable of bringing about that real victory, the resurrection, as of bringing about creation in the first place, with its own mandate to be fruitful. Evil, on the other hand, is sterility itself—an utterly vain attempt, contraceptive in character, to prevent the Living God from communicating life and love to his creatures that they might be fruitful.

Evil, as the first chapter of Genesis establishes, is no part of God's design; nor does it exist alongside God or what God has made. Evil is not something in itself. Yet evil is no illusion and, as we know, is highly consequential. That makes the mysterium iniquitatis a mystery indeed, but in no way excuses any failure to recognize or resist it. Evil must be fought, especially by adherents to the Easter faith, who have celebrated so great a victory in the fight.

Solovyov’s final book, prefaced at Easter in the year of his death, was written to press this point and to repudiate claims to the contrary. Some of the basics here, as he observes far too cryptically in his preface, he had only lately come to understand. His mystical sophiology, which shows more than a trace of the error of Jakob Böhme, points us in a universalist direction. Truth be told, it shows also a trace of narcissism, as such thinking usually does. The poles that excite it are the self and the cosmos, between which it easily becomes confused. And this he seems to have realized.

Not for nothing is the one monk who appears in Mr. Z.'s stories named for St. Barsanuphius and the other, "still more exquisitely," for St. Pansophius. What did the former say, when questioned about universalism?

Whatever you sow here, you will reap there. It is not possible for anyone to make progress after leaving this place. God will not labor to recreate the soul after anyone’s death. Brother, here is the place for labor; there is the place for reward. Here is the place of struggle; there is the place for crowns.

And what did the latter do, when questioned by the procurator in Alexandria during the Decian persecution? He boldly denounced error and faithfully confessed his Lord, thus suffering penalties that produced his death. This he did not fear because he knew that, if he suffered with Jesus, he would also be glorified with Jesus.

Such is true sophiology. The universalist must be sent back to the question about the state of his own soul, and the narcissist to the question as to whether he is prepared to lose his life, for Christ's sake, in order to save it. (Solovyov's fictional Barsanuphius is very hard on the narcissist!) Both must reckon with evil and the overcoming of evil, though not on their own, as if God in Christ had not already done that for them through the cross and resurrection.

But let us say more about evil. If evil is not just a nod to the primal Nothingness from which something, indeed anything, might come, but is rather a deliberate assault on that which God has made—made not from or even out of this putative Nothingness, but made with regard to nothing but God’s own good purpose and freely exercised power, for that is what creatio ex nihilo actually means—then evil really is evil. In which case, resistance may call for force, and even for martyrdom. If, on the other hand, evil is no more than a vague gesture, then so is martyrdom, and a strange gesture it is. We might even think it a peculiar folly. But what reality can we attribute to evil if God, who is goodness itself, is the only ground of reality? What can we say in defence of the martyr?

We can say that evil is real only as and because rational agents are permitted by God to will irrationally what is contrary to life and love, and sometimes also to do what they thus will. The resultant moral evil, which they make in themselves and of themselves, is very definitely real. So are its consequences, as our first parents quickly discovered, though we call these consequences “evil” in a different sense. The most severe consequence is when the evildoer, refusing to repent, arrives by divine justice at what is called the summum malum, being deprived of the presence of God and his goodness forever. Which invites the further remark that hell is no more an illusion than evil is an illusion. But hell will perdure as part of the triumph of God over evil, while evil will not perdure as if in triumph over God. The resurrection of Jesus demonstrates that God will by no means permit that, and that he is more than able to prevent it. It assures us of the ultimate impotence of evil and of the genuine potency of prayer, which evil men still seek to suppress.

Evil is real, in its way and for its time, because some creaturely agents really do pervert the gifts of God and seek to prevent them from fulfilling their purpose. But the triumph of the Crucified is real, not merely in its way and for its time, but absolutely and eternally real, in every way and for all time, for it is the triumph of God. Not merely as a metaphor is it real. Not even as a true "event" preserved in some Eternal Now. It is real as a person, as a living man who stands on his own two feet, who can breathe on us the bracing Breath of Eden, who can touch us and tell us to stand: "Do not be afraid; I am the first and the last, and the living one. I was dead, and see, I am alive forever and ever; and I have the keys of Death and of Hades."

Hence the triumph of evil is no triumph at all. The evil agent, for all the grief and agony he brings to the world, achieves, if he persists, only his own defeat. He will never see Eden. The doors of the Kingdom will not be open to him. But the man who trusts in God and obeys his Christ will rise as Christ himself arose. He will share the spoils of the divine victory over evil.

What Solovyov came to realize—no longer taking refuge in the common fancy about men of good will and good will among men, as if the resurrection put an end to our struggle with evil rather than putting it on an entirely new footing—is that the Kingdom will come only when Christ comes in his glory to smash every work of evil and to destroy the agents of evil in the Lake of Fire. It will not come before that, except by sacramental anticipation and brief hints of transfiguration. Neither will it come without that. Which is to say: it will not come without a real war between good and evil, a war that is already well under way and nearing its climax.

It was Solovyov's final burden to say this as clearly as he knew how; and to say, as our own catechism says, that "before Christ's second coming, the Church must pass through a final trial that will shake the faith of many believers." What follows he might almost have written himself:

The persecution that accompanies her pilgrimage on earth will unveil the "mystery of iniquity" in the form of a religious deception offering men an apparent solution to their problems at the price of apostasy from the truth. The supreme religious deception is that of the Antichrist, a pseudo-messianism by which man glorifies himself in place of God and of his Messiah come in the flesh.

The Antichrist's deception already begins to take shape in the world every time the claim is made to realize within history that messianic hope which can only be realized beyond history through the eschatological judgement. The Church has rejected even modified forms of this falsification of the kingdom to come under the name of millenarianism, especially the "intrinsically perverse" political form of a secular messianism. The Church will enter the glory of the kingdom only through this final Passover, when she will follow her Lord in his death and Resurrection.

Anyone taking up the same burden does well to remember that, if the crucifixion demonstrates that God is willing to be mocked—for God is great, not proud, as the incarnation already declares—the resurrection demonstrates that God cannot be mocked. God's purposes are sure, his judgments certain. What he means to bring about, he shall bring about. The whole earth will be full of his glory. Hence Paul's advice, which St. Barsanuphius urged us to take to heart: "Let us not grow weary in doing what is right, for we ourselves will reap at harvest time, if we do not give up."

Empty Dreams of Peace and Progress

Now to the simulacrum, which also concerns itself with the triumph of good, but so very differently. For convenience we may refer to it as the myth or cult of progress, terminology already employed in our earlier remarks on Solovyov's "Hole Worshippers," but its names are legion. Whatever we call it, we are speaking of something that consistently combines an air of moral superiority with a studied moral vacuity.

In his Three Discussions, Solovyov exposes the fact that the simulacrum never engages in a real war between good and evil. Indeed, it seeks constantly to evade any such thing. It is, in that respect, rather Hobbsean. War is evil, peace is good. The one passes away more or less naturally, and the other hoves into view, as soon as we acknowledge that peace is the one good we must seek. Peace on earth is then all but inevitable, given sufficient time. And the true believer (here he looks to Tolstoy) is the absolute pacifist.

The pacifist imitates Jesus in Gethsemane by bravely refusing, in the face of violence, to resort to violence. Thus does he disarm evil that good may triumph. Only he is actually disarming good that evil may triumph. He is disarming the Christ of the Gospels, who is deprived of his heavenly legions along with his earthly. Christ, for him, is merely an admirable, if somewhat tragic, source of pacific pronouncements and renouncements. He is no longer the one who declares, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword!" He can only be the one who says to Peter, "Put away your sword." Good is to triumph without a contest.

To think thus, suggests Solovyov, is to dream, as one still asleep. It is to ignore the prior command to Peter, the command to stay alert and pray that one not come unprepared into the time of trial. Which is just what Peter did, of course—he came unprepared, governed only by instinct, and he got everything wrong. He unsheathed his sword against man, without being told to do so, and he unleashed his tongue against God, as one ought never to do, denying his Lord with an oath.

That is how it goes for those who have not first deployed the weaponry of prayer, and especially those final petitions of the Lord's Prayer: "Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one." They pray indeed, "Deliver us, O Lord, from every evil and grant us peace in our day." But they do not recognize their day for what it is, or know what time of day it is, because they have been sleeping. They think they have enough swords, when no sword is called for. Or they think no sword necessary, not even the sword of testimony to Jesus, when that is just what is necessary. They are following Jesus, yes, but they are not allowing themselves to be led by Jesus. They are merely trailing him. And so they run away at the first sign of real trouble, as does the Prince in Pansophius' tale. Their faith is all in progress, in the kingdom of their fancy, the kingdom in which they suppose they will be among the great.

In this dreamy state, they cannot distinguish between their own will and the Father's. Nor can they discern the difference between good and evil or say anything very definite on that score. They see evil as nothing but an initial deficiency of good, a shortfall to be made up as history unfolds. Evil is conveniently associated with the past, or at least with what is said to be passing and must somehow be made to pass. That assignation is very reassuring, of course, though it may cause one to wonder why God didn't get the job done properly in the first place and whether man might do better himself with a little elbow grease. It may even make one wonder whether man needs any other saviour than man himself.

Such a man is set up for failure when the hour of temptation arrives, especially "the hour of trial that is coming on the whole world to test the inhabitants of the earth." In that hour, the hour that corresponds on a global scale to his own hour, Jesus promises to protect only the prepared: the wise virgins, not the foolish; those who have remained alert, not those fast asleep; those who are following, not those who are trailing. To the former he says what he does not say to the latter. "Because you have kept my word of patient endurance, I will keep you from the hour of trial." This does not mean that he will remove them from the world, where the trial is taking place, as dispensationalists or rapture theorists imagine. It means that he will keep them safe in the world, for they will recognize the hour and see the trial for what it is. He will deliver them from temptation and from the Evil One. He will not permit them to fall prey to the great deception through which the nations are lured into their final disaster. It is a terrible thing to fall into the hands of the living God, who is by no means a pacifist. It is a wonderful thing, however, to be found safely under his wing when disaster arrives.

For this very reason God sends upon them a deluding influence, that they might credit the lie, so that they should be judged—all those who have not believed in the truth but taken pleasure in unrighteousness. But for you we ought always to render thanks to God, brethren beloved by the Lord, because he selected you as firstfruits for salvation in consecration of spirit and conviction of the truth, unto which he called you through our gospel. (2 Thess. 2:11–14, author's trans.)

The myth of progress—of good gradually emerging triumphant over evil in a grand conquest that sublates every actual moral contest; that renders moral struggle itself irrelevant, retrograde, impolite, even violent; that knows nothing of consecration of spirit and conviction of the truth—is the precondition for the great deception. It is an instrument of judgment on those who suppose that Jesus Christ is not risen from the dead and cannot himself exercise judgment. By it, what is not real is regarded as real and what is real is regarded as unreal. By it, disease prevails in the name of health, violence in the name of peace, anarchy in the name of order, bondage in the name of freedom. And by it, in due course, Antichrist will be regarded as Christ.

Solovyov's fictional Soter Mundi becomes a saviour by succumbing to the very temptations Jesus himself overcame. The Lukan ordo temptationis is inverted, and the details altered to suit a narcissist, but the pattern is the same. He is miraculously delivered from despair and death, imbued in secret with the authority of his infernal father, then enabled to transform prior failure into startling success. Thus empowered, he tempts in turn (here the ordo is restored) the inhabitants of the world, who are seduced by their need or greed for material goods, over which he has gained full control; by their desire for order and in some cases for power; and by the provision of amusements, tinged with religious mystery. In a time of distress and anxiety, when hope in peace, prosperity, and progress is failing, he reignites it by the sheer force of his own personality and the impressive reach of his plans.

After this, he targets Christians specifically, in the fashion foreseen by Vincent Ferrer, but with specific permutations adapted to the broken fragments of Christendom. Catholics are tempted through their love of hierarchical unity and worldly power; the Orthodox through their pride in ancient local tradition; Protestants through their fixation on personal faith and "free examination" of scripture. The temptations are successful, by and large, but in each fragment of his people God has retained a faithful remnant, which he gathers up and reunites without loss of any essential element. They come together by seeing the real as truly real, and the simulacrum as a simulacrum.

Authority, antiquity, and personal faith thus unite, per that other prayer of Jesus, to strike the enemy with a sword fit for the task. And what is that sword? Pure loyalty to Jesus, the loyalty his disciples failed to display in the Garden, as had their first parents. Faithful confession, before God and man, of the greatest gift of God—the gift given once from the womb of Mary and again from the Garden's open tomb. The faithful banish all temptation with a simple assertion: "What we value most is Christ himself." And they press a simple demand of the putative man of peace: Recognize Jesus as the risen and coming Lord and we in turn will recognize you as a legitimate authority, pro tempore, among men.

By thus atoning for their own sins, though not for the sins of their false brethren, the remnant are readied (together with Jews) to enter the Kingdom, to join that city in which there is a truly harmonious communion of those able to enjoy God and one another in God. Which they will do at the third giving, the giving that opens neither a womb nor a tomb but heaven itself, that the true Saviour, who passed through both, may appear in his awful splendour.

Now that really is progress! It comes, not from denying the reality of evil, but rather from confronting it. Which is just what Solovyov asks his readers to do, from beginning to end, through moments humorous and vignettes horrific. At the climactic moment in Pansophius' Short Tale, Elder John, now face to face with the evil Emperor—whose peace-and-security mask is slipping and whose vegetarian ideals are beginning to look rather carnivorous—makes the requisite identification. "My dearest ones, it is Antichrist!” And the Prince, who out of curiosity or shame had stolen back to hear more of the story, now runs away again; for he cannot bear to look evil in the eye.

Refusal by the faithful to avert their gaze proves fatal. In a mirror-image of the Lukan scene in which Ananias and Sapphira are struck down by God before Peter and John, Elder John and Peter II are struck down by the antipope, Apollonius, who doubles as False Prophet and pyrotechnic miracle-worker. (The Protestant leader, Ernst Pauli, gets a pass because Protestants have been slow to grasp the principle of headship and someone must be left to do that; they have not, however, been slow to grasp the principle of martyrdom.) But these two witnesses, having dared to strike the true blow on behalf of Christ, receive as he did a reversal of verdict from the court of last appeal. "The breath of life from God entered them, and they stood on their feet, and those who saw them were terrified."

A Personal Fight to the Finish

Lady: But what is the absolute meaning of this drama? I still do not understand why the Antichrist hates God so much, while he himself is essentially good, not evil.

MR. Z.: That is the point. He is not essentially evil. All the meaning is in that.

The perceptive reader—even if ignorant of the remaining details of Solovyov's book and Pansophius' tale, which I leave to his or her own discovery—will anticipate that something remains to be said in the present essay. It can be said in this very connection.

The Antichrist is not essentially evil because God is not evil at all. God, as we have said, is goodness itself and, in his willing and making, wills and makes only good. It follows that there is no evil essence; nothing and no one is essentially evil, not even Lucifer. Evil is something we creatures make from good ingredients, including the ingredients of which we ourselves consist, by deliberately disordering them. Solovyov, while taking evil with the utmost seriousness, wants no false reification of evil. Hence he is careful to say that, just as the resurrected Christ is a person, so also Antichrist is a person and not merely a force or principle. Antichrist cannot be reduced to what political theologians like to call "systemic evil."

The will that wills evil can certainly will in a way that produces systemic effects. It can will with remarkable foresight and a refined technique for achieving what it wills. One will, even a very narcissistic will, can cooperate with another, achieving quite extraordinary levels of coordination. Momentum can be created, a momentum that carries forward the evil design even beyond the lifespan of its designer. Unlikely partners can conspire together to fulfill that design, as they did against Jesus in Jerusalem and are doing again now. But without the will that wills evil, there is no evil. That is not to say that there is no such thing as an intrinsically evil action; none, however, takes place apart from the determination of an active agent, who qua acting agent remains essentially good with a goodness he will lose only upon reaching the summum malum, where he will no longer be able to act (hence Jesus' "gnashing of teeth" metaphor, that being something we do primarily in our sleep).

What the scriptures say about the progress of evil in the direction of Antichrist, then, cannot be regarded as an attempt to convey only a general possibility or tendency, in the aggregate effects of which we may hope to find as much ebb as flow. The man of lawlessness is coming. He is coming as a society, yes, and as a regime fitting for that society; but he is also coming as a particular man. The hour of that man is approaching. He shall "be revealed in his own proper time," which is not far off; for the mystery of lawlessness is already at work, and long has been.

Many there are, including Christians, who will instinctively prefer this refined brigand (no crude Barabbas, he!) to Jesus. And many there are who have become so careless on questions of moral truth as to be incapable of seeing that any choice is required, or at least any that can't be made with a handy Quick Recognition code. Others there be, fewer in number but greater in influence, who have imbibed their Lessing, Hegel, Mill or Marx, even that Jesuit trickster Teilhard, so deeply as to divinize History. That is how they have prepared themselves to be on the right side; unless they have imbibed something still darker, drinking from the cup Nietzsche passed them.

The result is the same. None has a god who can save from death, much less from hell. All worship Mammon, or even Moloch. They mean to gain the whole world, perchance to preserve the world itself from death—sustainable development!—until they no longer need it. But Mr. Z. is right. One by one, they forfeit their own souls, with none to rescue them. Refusing to receive the Father's testimony to the Son, or to act accordingly, they side with progress, drink a toast to peace and security, and "hasten the day" only of their own demise. They are indeed the hollow men.

In the Apocalypse it is written:

The beast that you saw was, and is not, and is about to ascend from the bottomless pit and go to destruction. And the inhabitants of the earth, whose names have not been written in the book of life from the foundation of the world, will be amazed when they see the beast, because it was and is not and is to come.

Is that not John's way of telling us that there is a gaping hole in our culture? One there is, and only one, "who is, and who was, and who is to come." His name is YHWH. And because that one has come—his name in coming is Yeshua—the other, the pretender, the diabolos, now is not; neither he nor the beast domiciled with him have their former power. They will be again, however, when the ancient design is fully updated. The devil then will sally forth, leading his beast, on the head of which will appear the boastful horn who is to enjoy, for a moment, his own parousia. God will allow it, St. Michael will be told to permit it, until divine judgment, richly deserved, is meted out once and for all.

Then those legions of "mighty angels in flaming fire," whose commander held them in reserve while Peter inadvisably drew his own feeble sword, will themselves sally forth. That, in truth, will be no contest and of the Kingdom of Yeshua there will be no end. On him is being built a new and everlasting culture, a eucharistic culture that opens upwards rather than downwards. For it is humility, as Augustine observed, "that builds a safe and true way to the heavens" (Civ. 16.4).

Solovyov supposed that all this would come to pass in our century or soon thereafter. Since his death in AD 1900, it does seem that the world has been marvelously prepared for each of the three temptations. Man hungers for bread or, we are warned, soon will. He yearns for stable authority and effective power, however draconian. He thirsts for mystery and meaning, even in the most peculiar places. All this and more will be offered, through the miracles of technology and, if Solovyov is right, by force of personality. (Where personality won't persuade, no doubt policing will suffice.) A deluding influence has already gone forth and preliminary articles of betrayal, marketing the Coming Man to the churches, were drafted some time ago. Much, though not quite all, is in readiness.

There is an hour of testing that is coming upon the whole world. This we know by dominical authority. Who will pass the test, save those who have received the testimony of the real victory over evil in the real resurrection? Whatever their own worldly fate, we have it also on dominical authority that they shall not fail to have a part, a glorious part, in that.

© D. B. Farrow 2022. Solovyov’s book can be found here or (with an insightful foreword and an absurd theosophist afterword) here. A brief excerpt follows below.

image

Soon after the publication of “The Open Way,” which made its author the most popular man ever to live on earth, an international constitutional congress of the United States of Europe was to be held in Berlin. This Union, founded after a series of international and civil wars which had been brought about by the liberation from the Mongolian yoke and had resulted in considerable alteration in the map of Europe, was now menaced with peril, not through conflicts of nations but through the internal strife between various political and social parties. The principal directors of European policy, who belonged to the powerful brotherhood of Freemasons, felt the lack of a common executive power. The European unity that had been obtained at so great a cost was every moment threatening to fall to pieces. There was no unanimity in the Union Council or “Comité permanent universel,” for not all the seats were in the hands of true Masons. The independent members of the Council were entering into separate agreements, and this state of affairs threatened another war. The “initiated” then decided to establish a one-man executive power endowed with some considerable authority. The principal candidate was the secret member of the Order—“the Coming Man.” He was the only man with a great worldwide fame. Being by profession a learned artilleryman, and by his source of income a rich capitalist, he was on friendly terms with many in financial and military circles. In another, less enlightened time, there might have been held against him the fact of his extremely obscure origin. His mother, a lady of doubtful reputation, was very well known in both hemispheres, but the number of people who had grounds to consider him as their son was rather too great. These circumstances, however, could not carry any weight with an age that was so advanced as to be actually the last. “The Coming Man” was almost unanimously elected president of the United States of Europe for life. And when he appeared on the platform in all the glamor of youthful superhuman beauty and power and, with inspired eloquence, expounded his universal program, the assembly was carried away by the spell of his personality and, in an outburst of enthusiasm, decided, even without voting, to give him the highest honor and to elect him Roman Emperor.

Thank you for this wonderful article. It contains several themes that I have been meditating upon during Eastertide: witness/martyrdom, resistance, political theology, and most of all, the sterility of evil. Of course, that was only a first pass. All such fine things deserve repetition.

Hello - I think I might reply to this at length at some point. Could be instructive. Thank you!

-aXpH