The Hole in Your Culture

Address to a student conference on Culture and Value at the Dominican University College in Ottawa

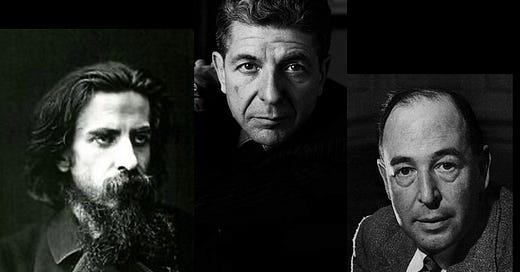

Solovyov, Cohen, Lewis: Did they know something we don’t?

In his Notes Towards the Definition of Culture (1948), T. S. Eliot writes that "all parties live in amity, so long as they accept some common moral conventions." While that may seem rather general and somewhat overstated, it is buttressed by an appeal to religion: "The formation of a religion is also the formation of a culture."

Religion and morality lie at the heart of culture. "Without a common faith," says Eliot, "all efforts towards drawing nations closer together in culture can only produce an illusion of unity." Our late friend, Richard John Neuhaus, made the same point quite concisely when founding First Things: “Culture is the root of politics, and religion is the root of culture.”

Eliot rightly insists that, "for the most part, it is inevitable that we should, when we defend our religion, be defending our culture, and vice versa: we are obeying the fundamental impulse to preserve our existence." He allows, however, that here "we make many errors and commit many crimes—most of which may be simplified into one error, of identifying our religion and our culture on a level on which we ought to distinguish them from each other."

This is true, as the past two years demonstrate; and we cannot distinguish them properly if we do not know how to think theologically. "The refinement or crudity of theological and philosophical thinking is itself, of course, one of the measures of the state of our culture; and the tendency in some quarters to reduce theology to such principles as a child can understand or a Socinian accept, is itself indicative of cultural debility."

Eliot, presumably, understood most of that already in 1927, when he converted from Unitarianism to Christianity; more specifically, to Anglo-Catholicism. But our difficulty today, I venture to say, is that we are culturally debilitated —all but paralyzed—in just this sense. We have fancied that we could defend our culture without defending our religion, and we have wound up being unable to defend either. There is a hole in our culture where religion ought to be, and there's a hole in our religion where theology ought to be.

Dystopic Consequences

"It is impossible," declares Christopher Dawson in Enquires into Religion and Culture (1933), "to exaggerate the dangers that must inevitably arise when once social life has become separated from the religious impulse." Yet it seems we have altogether underestimated them.

We still sing: God keep our land / glorious and free / O Canada / We stand on guard for thee. Just as we no longer know who or what is meant by "God," however, we no longer know how to stand on guard. We neither bear the sword (porter l'épée) in defence of our freedoms, nor carry the cross (porter la croix) in witness to our Lord, from whom we learned of freedom. Our land is very far from being glorious and free. We do not grasp the supremacy of God, or even seek to grasp it; hence we no longer grasp the rule of law either, which even in Charter form is disintegrating before our eyes. What we see instead is police bearing batons to crush those who believe in freedom, at the behest of those who believe only in their own power and privilege.

Among the citizenry, there are still courageous freedom fighters; honest lawyers and faithful judges; doctors with borders, that is, with consciences; leaders, lay and clerical, who act out of principle, not out of fear or greed. But they are few, too few. Of the rest, St. Vincent Ferrer was right. Any religious impulse they retain is falsified or overcome by their desire for gold and silver and honours. Gog and Magog, "both hidden and open evil," conspire together. "Temporal lords and ecclesiastical prelates, for fear of losing power or position," collaborate. Religious, priests, and laity betray the gospel. Those who refuse are attacked by people in high places and low, and especially by low people in high places.

The bleak picture painted by Leonard Cohen in his 1992 song, The Future, from which I have taken my title, may seem to do what Dawson thinks impossible; that is, to exaggerate the effect of the loss we are considering:

Give me absolute control

over every living soul

And lie beside me, baby,

that's an order!

Give me crack and anal sex

Take the only tree that's left

and stuff it up the hole

in your cultureGive me back the Berlin wall

give me Stalin and St Paul

I've seen the future, brother:

it is murder

But Cohen is onto something important here. A wall divides. It distinguishes and divides. "Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall," cried Ronald Reagan at the Brandenburg Gate in 1987. The gate was opened two years later, people poured through from East to West, and the wall came down. But to what end, asks Cohen—has the West anything left with which to save the East? Has it not abandoned its own proper foundations? The difference that matters is not the difference between East and West; the one is as capable of brutal tyranny as the other. The difference that matters, East or West, is the ability or inability to make real moral distinctions.

That is what concerned C. S. Lewis back at the end of the war that produced the wall. In That Hideous Strength (1945), his hero speaks of a poison, concocted in the universities, that has been spat everywhere. Wherever we look, says Ransom to Merlin, we find its traces. "We find the machines, the crowded cities, the empty thrones, the false writings: men maddened with false promises and soured with true miseries, cut off from Earth their mother and from the Father in Heaven. The shadow of one dark wing is over all Tellus."

Lewis's dystopic vision, as described in that novel and analyzed in The Abolition of Man, which appeared in 1943, is no less bleak than Cohen's. And what was the poison in question? Its main ingredient was atheistic evolutionary optimism about man's triumph over nature, now that neither man nor nature were viewed theologically, as the product of divine design and and the object of God's providence. To conduct this battle, man would have to step outside of his own nature; or rather, outside everything natural but what Nietzsche called the will to power. Man would have to go beyond good and evil.

Lewis set about explaining how this was happening and what it might look like and to what end it must come. But Cohen captures the explanation quite concisely in a few lines of his own:

Things are going to slide, slide in all directions

Won't be nothing, nothing you can measure anymore

The blizzard, the blizzard of the world

has crossed the threshold

And it has overturned

the order of the soul

Now, the order of the soul is the work of reason, both speculative and practical reason, dividing truth from error and distinguishing between good and evil. It is the work also of the will, which, as the mind recognizes rectitude, freely aligns itself with what has rectitude, thus maintaining its own rectitude. Rectitude, as Anselm tells us in De Veritate, is simply "right existence or existing rightly." The rightly ordered soul is the soul that wills what it ought for the reason it ought. It is the soul that preserves the justice which which God has endowed it. As Lewis says, it is the soul that recognizes and respects the Tao, choosing to stand within it rather than to step outside it into the void.

Such was not Cohen's soul, perhaps, or not consistently. But Cohen could at least lament the fact and pray for its overcoming, as he did in an earlier song, a hopeful and hauntingly beautiful song from 1984, with its hint of resurrection faith:

If it be your will

If there is a choice

Let the rivers fill

Let the hills rejoice

Let your mercy spill

On all these burning hearts in hell

If it be your will

To make us well

All this is bound up with the religious impulse, of course; that is, with recognition that the soul itself is ordered to God and has from God its capacity both to recognize rectitude and to remain rectitudinous. It is bound up with its vocation to receive what God gives and to give thanks for what it receives. It is bound up, in brief, with what Christians call the soul's eucharistic vocation, and with the deconstruction and reconstruction of the soul that cries to God from Golgotha.

If it be your will

That a voice be true

From this broken hill

I will sing to you

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

But the world in which we find ourselves today, whether in East or West, is not that world. It is a world in which it is supposed that society and hence also the soul, or the soul and hence also society, can be organized without reference to any of this. It is a world in which the very idea of the soul is opaque, at best, if not missing altogether, as the practice of abortion attests.

Give me back the Berlin wall

Give me Stalin and St Paul

Give me Christ

or give me Hiroshima

Destroy another fetus now

We don't like children anyhow

I've seen the future, baby:

it is murder

Luca Signorelli

Appearance and Growth of the Hole

If you seek a philosophical explanation for the loss, you can find it in The Abolition of Man. I think, however, that we must look for it much further back than Lewis looks. As I tried to explain in Theological Negotiations, it appears with the first stirrings of nominalism, a millennium ago, in the circle round Roscellinus, whose error slowly mounted into the great storm that has overturned the order of the soul, just as Anselm knew it would, if left unchecked. The new ideas, he warned, were incapable of accommodating fundamental theology: the doctrines of the incarnation and the Trinity. If they prevailed, they would bring the whole house down. Which is just what has happened, though few noticed it happening.

Skeptical materialism was the necessary byproduct of nominalism, and into the mental and moral vacuum thus created rushed, in due course, the blind optimism of eugenic evolutionism. That in turn triggered the process described by G. K. Chesterton in Eugenics and Other Evils and later by Lewis: a process of the undoing of the soul by detaching fact from value, value from virtue, virtue from reason, and reason itself from the Tao. The moral structure of man and of the universe, accessibility to which we usually speak of under the rubric Natural Law, began to be regarded as no more than a temporary artifact produced by a certain chance configuration of human culture and mutating with man himself. (The assumption that man does mutate was attacked by Chesterton in The Everlasting Man, but we must leave that aside; on Chesterton's anticipation of the present crisis, see my three-part essay, Anarchy from Above.)

This attacked moral distinction-making at its very root, though few were as bold as Nietzsche in admitting it. It attacked in particular the Christian principle that it is never licit to do evil that good may come and led to an alternative notion that today is worryingly familiar: the neo-utilitarian notion of the "recycling" of evil, as some of the transhumanists like to put it. We may indeed do evil that good may come, for evil is as much a part of the world process as good, and just as necessary to the progress of man. We might turn back to Eliot here, or perhaps to Yeats, but Cohen again puts it succinctly:

There’ll be the breaking of the ancient western code

Your private life will suddenly explode

There’ll be phantoms

There’ll be fires on the road

The anti-hero in That Hideous Strength, Mark Studdock, serves as the very epitome of one who is culturally, because religiously and theologically, debilitated and, just so, in deadly danger of being seduced by such ideas as the recycling of evil. Drawn into the company of those who have broken with the Tao—with the ancient code that is not only Western but universal—his private life does indeed explode. He becomes the target, first, of deliberate chaos, to break down his resistance, and then, in the so-called Objective Room, of methodical attacks on his very notion of rectitude. It is a dark picture that Lewis paints, albeit one on which a heavenly light shines, ultimately dispersing the darkness and redeeming Studdock: not, however, before the collapse of his world and the threatened collapse of civilization itself.

There'll be phantoms, there'll be fires on the road: deliberate chaos and organized rituals of destruction. Is that not what we ourselves have been witnessing these past two years? We have been haunted by a spectral virus, from which we have hidden our faces, thus becoming spectres ourselves; a virus falsely said to threaten every human life, to require the sacrifice of "the old normal," of every familiar economy whether financial or medical, political or religious, until—vacina salva!—mass injection with miracle vaccines saves us all from death and we awake to the world of the new normal.

As in Lewis' novel, there is a carefully manufactured crisis, a bonfire of the vanities that has consumed what we did not even know were vanities: our Constitution, our freedom to determine for ourselves what we should do or where we should go, our liberty to be who and what we are, even under the skin. Give me absolute control / over every living soul / Roll up your sleeve, baby / that's an order. The human being has become a hackable animal, as Yuval Harari warns, and those who stand to profit from the process will do so, in league with those who are determined to direct the process—to be what Lewis calls the Conditioners or Controllers.

The Shadow of that Hyddeous Strength

In The Abolition of Man Lewis recalls for us Marlowe's Faustus, who thirsts, not after truth, but after power. For Faustus "a sound magician is a mighty god"; all things become subject to his command. Lewis sees modern science—the science, as we are now taught to say—in that light. Its true object "is to extend Man’s power to the performance of all things possible."

The practitioner of this science "rejects magic because it does not work; but his goal is that of the magician." Like the magician he often discovers, as we ourselves are discovering, that his scientific magic does not work either. But no matter. Science is busy freeing us from the old master, Nature, through hygiene and contraception and genetic tinkering; just as philosophy is busy freeing us from Duty, through absolute autonomy of will. While the one scrubs the world of microbes to please the macrobes, the other scrubs the world of morals, for the same purpose. Not to put too fine a point on it: the hole in our culture appears to be bottomless. It opens downwards, ad infernum, where the macrobes dwell, or soon will dwell.

If you think this overwrought, the product of a fevered theological brain, I urge you to pay closer attention to the similarities between, say, the work of SAGE, Britain's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, and the work of Lewis's NICE, the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments. The former was conceived subsequent to the "mad cow" or BSE crisis and activated for the swine flu pseudo-crisis of 2009, which served as a dry run for covid. Being but an ad hoc advisory committee, SAGE is a far cry from NICE, of course, but one notes that it has met more than a hundred times during covid, and that the government it has been advising has deployed techniques similar to those of NICE, with analogous effects. Establishment of public-private partnerships, control of the press, appeal to false modeling, staging of provocations that cause fear and division, and especially the exercise of sweeping emergency powers to effect fundamental changes both in political decision-making and in policing: all this, or a great deal of it, Lewis anticipated.

The introduction of penal concepts and techniques, especially lockdowns, and projections onto the general public of crimes authorities were themselves committing—Who really did kill granny?—raise disturbing questions about what has been going on behind the scenes. But nowhere, perhaps, does the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments come more readily to mind than in the matter of Emergency Use Authorization vaccines that mysteriously become all but obligatory. If one cannot really think "NICE" today except as a chimera comprising elements of SAGE, the Wellcome Trust, ARIA or DARPA, and the World Economic Forum, one can at least grant that Lewis understood the nature of the beast. And he knew that its purpose went far beyond the handling of occasional challenges such as a dangerous pathogen or a banking crisis or the domestic effects of a war. The planners want to plan, not merely to react. The controllers mean to control. They mean to be saviours of the world, not simply crisis managers.

What's more, they have a kind of resurrection faith of their own, in lieu of the old Christian version. "This Institute," declares NICE scientist and chief medical officer, Filostrato, "is for something better than housing and vaccinations and curing the people of cancer. It is for the conquest of death: or for the conquest of organic life, if you prefer. They are the same thing. It is to bring out of the cocoon of organic life ... the man who will not die, the artificial man, the man free from Nature."

Just there, you say, the signs of brain-fever are undeniable. No such grandiose claim will ever be made by a SAGE scientist, surely! Yet such claims are made by the likes of Harari. Harari agrees with Filostrato that we have already witnessed "the beginning of all power." And he knows well enough, I expect, what Lewis knows; viz., that man's power over nature really means "the power of some men over other men, with Nature as the instrument." Moreover, he knows that in the last analysis "there is no such thing as Man," that man is "just a word." Did Roscelin not already explain that a thousand years ago, to Anselm's horror?

Lewis echoes Anselm's objection. This kind of thinking, "if not checked, will abolish Man." And the threat is every bit as real in the West, from which it came, as in the East, to which it went. It is a threat, he says, as much among Democrats as among Communists or Fascists.

The methods may (at first) differ in brutality. But many a mild-eyed scientist in pince-nez, many a popular dramatist, many an amateur philosopher in our midst, means in the long run just the same as the Nazi rulers of Germany. Traditional values are to be ‘debunked’ and mankind to be cut out into some fresh shape at the will ... of some few lucky people in one lucky generation which has learned how to do it. The belief that we can invent ‘ideologies’ at pleasure, and the consequent treatment of mankind as mere ὕλη, specimens, preparations, begins to affect our very language. Once we killed bad men: now we liquidate unsocial elements. Virtue has become integration and diligence dynamism, and boys likely to be worthy of a commission are ‘potential officer material’. Most wonderful of all, the virtues of thrift and temperance, and even of ordinary intelligence, are sales-resistance.

Sales-resistance, at the moment, we call vaccine hesitancy; indeed, the planners were calling it that before the pandemic. Soon enough, we shall be calling it "digital identity reluctance," and charging the laggards with being a fringe minority for which there is no room in our society. Man has become a hackable animal? Then hacked he shall be! We live in a digital world? Then only those who are prepared to be digitalized may live with us! We will be their only source of truth, their only source of identity, their only source of safety. We will build for them a tower that reaches the clouds of heaven, and there they will at last dwell in peace.

Peter Bruegel the Elder

The shadow of that hyddeous strength, sax myle and more it is of length (David Lyndsay, 1555). And what, this time, stands in the way of its completion? The cherubim? But we don't believe in cherubim. Certainly not the churches, though they still speak of consorting at their altars with cherubim. There'll be phantoms, there'll be fires on the road. And in these fires the churches too will be consumed. Have not most of their mentors and members already begun fleeing towards the tower for safety?

"No culture has appeared or developed except together with a religion," says Eliot. Will the technocratic culture upon which we are now entering "by encouraging cleverness rather than wisdom"—the hollow culture of hollow men, for which liberalism prepared the way by its refusal of anything very definite in the way of religion; the anti-culture of "the artificial, mechanised or brutalised control which is a desperate remedy for its chaos"—be any exception? No, it too will be religious, as Hitler himself prophesied, or it will be no culture at all. And its religion, as Harari predicts, will be the religion of the Man-god, not of the God-man. But man, remember, is just a word; church also, or so it seems. For many churches, as I have observed before, are become mere creatures of the State.

In the divine fire on Sinai, the burning bush is not consumed. That is what makes it so fascinating to Moses, who, in seeking to know why that is so, quickly discovers that he is standing on holy ground. But in the macrobic fires now raging, the very first thing we discover is that there is no holy ground. Signs were immediately posted on the doors of our churches instructing us, not to take off our shoes on entry, but rather not to enter at all. Later we were told we could go in if we were dressed like firemen and scrubbed our pews; still later, that we could go in without this hygienic para-liturgy if we first offered a pinch of incense to the emperor in the form of a vacina salva attestation. At every stage, it was made clear that churches will not be permitted to stand in the way of the New World Order. Sadly, it also became plain that few of them intend to do so.

The Hole Worshippers

A hundred and thirty years ago, Vladimir Solovyov, who was a student of materialism and of religious and moral problems, saw all this coming. In the preface to his final work, War, Progress, and the End of History—a preface he produced at Easter, AD 1900, just before his death—he displays the conversion in his own thinking which both Bakshy and Miłosz remark in their introductions, a conversion away from the realized eschatology that characterized his culture. Solovyov opens with a question directed to evolutionary optimists and their cult of progress, including those who regard themselves as Christians: "Is evil," he asks, "only a natural defect, an imperfection disappearing of itself with the growth of good, or is it a real power, possessing our world by means of temptations, so that for fighting it successfully assistance must be found in another sphere of being?"

Now, we may wish to quibble with any description of evil as a real power, as opposed to a kind of non-being, a mere defection from the good; for all that is, is made by God and God makes only what has both being and goodness. But of course evil is a real power when that which is real and good—an angel, or the soul of a man—turns itself away from God, from Goodness itself, willing and doing what it ought not. Though only a "quasi-something," to use Anselm's expression, evil is, in this sense, something all too real. That is why we are taught by Jesus to petition Heaven, another sphere of being, for help against it. "Lead us not into temptation (εἰς πειρασμόν) but deliver us from the evil one" (ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ).

Solovyov, who apparently recognized the danger of his Godmanhood concept inverting itself into an immanent, satanic Mangodhood concept, determined to present boldly "the question of the struggle against evil and of the meaning of history." He determined "to set out clearly and prominently the vital aspects of Christian truth, in so far as it is connected with the question of evil," for he knew very well that the hole in our culture is a theological one.

In his preface, he recounts a curious rumour from the countryside about a new religion that appeared in the eastern provinces some decades earlier:

The religion, the followers of which called themselves "Hole drillers," or "Hole worshippers," was very simple; a middle-sized hole was drilled in a wall in some dark corner of a house, and the men put their mouths to it and repeated earnestly: " My house, my hole, do save me !" Never before, I believe, has the object of worship been reduced to such a degree of simplicity. It must be admitted, however, that though the worship of an ordinary peasant's house, and of a simple hole made by human hands in its wall, was a palpable error, it was a truthful error; those men were absolutely mad, but they did not deceive anybody; the house they worshipped they called a house, and the hole drilled in the wall they reasonably termed merely a hole.

Simplicity indeed! This theological reductio ad absurdum certainly satisfies Eliot's criterion of religious and cultural failure.

As the book unfolds, we learn that very urbane and sophisticated people in Russia and the West have been busy inventing a similar religion on a grand scale, one equally mad but much more deceptive. It is a religion that denies the reality of evil, that supposes no war with evil necessary, that thinks of the modern age as an age of progress towards perpetual peace. It is ostensibly Christian, but its "Christianity" is no more than a vague social ethic, an optimistic inter-faith ecumenism that refuses any risk of becoming doctrinaire. It gives virtually no thought to the life of the world to come; it is all about life in this world and how to improve it.

Solovyov teases out the problem with this immanentist religion through parlour discussions that take place between a General, a Prince, a Politician, and the lady whose parlour it is. Through a fifth party, the mysterious Mr. Z, his own voice sounds. He shows where this sort of religion (of which Tolstoy was a proponent) leads culturally. He puts his finger on the fact that it eschews careful definition and can never quite decide whether or how to distinguish between good and evil, except to suggest that the former is something we are on the way to and the latter something we are on the way from. The real problem with it, however, which manifests itself as a disinclination to concern itself with scripture, creed, or dogma, is that here one simply does not believe in the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. Disbelief in the bodily resurrection of Jesus is precisely how the hole in our culture must be specified, according to Solovyov.

This leads him ultimately, as any serious consideration of the subject must, to the terminus of history at the parousia of Jesus. The book concludes with its famous Short Tale of the Antichrist, in the form bequeathed to Mr. Z by a certain Father Pansophius, named for the third-century martyr who denounced pagan errors. One of the leading characters in that tale is Professor Ernst Pauli, a Protestant biblical scholar of convinced credal faith. He and his two colleagues, Pope Peter and Elder John, do battle in the church with the anti-culture of the Antichrist. What they must battle with in particular is the anti-religion of those have succumbed to what we may call an Ernst Troeltsch type of faith, a faith that knows no fall and hence no redeemer. Jesus is not the Son of God incarnate, crucified, resurrected and ascended. He is simply a symbol of the divine spirit at work in history, with History itself the only redeemer we need. In every era, as Troeltsch says, man is meant to seize the divine as it appears in his time. And the divine can never be circumscribed in advance, much less fixed in some bygone period or phase. To think such a thing would be to fall.

Such are the doctrines of the cult of progress, which presuppose that evil is nothing more than a shortfall of the good that is steadily accruing to us. In his relentless attack on this cult, Solovyov posits a counter-thesis in which evil is understood to be parasitic on good: "It is absolutely certain that though the plus may grow, the minus grows as well, and the result obtained is something very near to nil." Or as Lewis puts it in That Hideous Strength: "Good is always getting better and bad getting worse; the possibilities of neutrality are always diminishing." The nil result is evident from the fact that no advance ever made by the race has had the slightest impact on the stubborn datum of death. This tells us that evil really exists and (as Mr. Z observes) that it "finds its expression not only in the deficiency of good, but in the positive resistance and predominance of the lower qualities over the higher ones in all the spheres of Being."

There is an individual evil when the lower side of men, the animal and bestial passions, resist the better impulses of the soul, overpowering them, in the great majority of people. There is a social evil, when the human crowd, individually enslaved by evil, resists the salutary efforts of the few better men and eventually overpowers them. There is, lastly, a physical evil in man, when the baser material constituents of his body resist the living and enlightening power which binds them up together in a beautiful form of organism resist and break the form, destroying the real basis of the higher life. This is the extreme evil, called death. And had we been compelled to recognise the victory of this extreme physical evil as final and absolute, then no imaginary victories of good in the individual and social spheres could be considered real successes.

Hence arises the now secret, now open, idolization of death that we are beginning to experience, and the resurgent religion of fear it entails. And yet, we have not been so compelled, have we? We do not have to recognize the victory of death. For we have heard of the victory of Jesus over death, which unlike the hole drilled in the peasant's wall leads somewhere, not nowhere. It leads to life eternal, for it is an opening made in death itself, by the goodness of God. "If I believe in good and its own power,” maintains Mr. Z, “whilst assuming in the very notion of good its essential and absolute superiority, then I am bound by logic to recognise that power as unlimited, and nothing can prevent me from believing in the truth of resurrection, which is historically testified."

Whence, then, the hole worshippers who today seem to be drilling a hole in every single wall of our cultural home, from conception to natural death? And whence those supposedly educated hole worshippers who "do not call themselves by this name, but go under the name of Christians," passing off their teaching as gospel when it is actually a "Christianity without Christ and the Gospel," a gospel "without the only good worth announcing—viz., without the real resurrection to the fulness of blessed life"? All this, says Solovyov, is "as much a hollow space as is the ordinary hole drilled in a peasant's house."

The Remedy

To escape the fate this hollowness portends, Solovyov proposes, the thinking man must believe the Bible and the simple Bible-believing man will himself have to become a thinking Christian, a theological Christian, lest he fall prey to Antichrist. What was it Paul said? Be infants in your hearts, but not in your heads. That man, the son of perdition, will be “equally far both from infantile intellect and from infantile heart,” from child-like trust. The believer must match him in the former without following him in the latter. He must be as alert of mind as he is loving of heart.

Well, are we? Or was T. S. Eliot was talking about us when he wrote:

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Our response to the pandemic, I fear, has revealed our hollowness. Pulverized by propaganda, we were driven into dry cellars and there we remained. Though we had been entrusted with the gospel of the resurrection, with the good news of a love that casts out fear, we stayed silent. Or rather, we fell all over ourselves to identify our religion with the imploding culture, over which the merest threat of death now reigned gloriously. Safety was the name of the hole our neighbours were worshipping, and we worshipped with them. "My house, my hole, do save me!"

Yet we have had no safety. We have only been impelled from one crisis to the next, with more and more casualties. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer says in his Ethics, "There is no clearer indication of the idolization of death than when a period claims to be building for eternity and yet life has no value in this period, or [note bene!] when big words are spoken of a new man, of a new world and of a new society which is to be ushered in, and yet all that is new is the destruction of life as we have it." Just like Solovyov, Bonhoeffer insists that "the miracle of Christ's resurrection makes nonsense of that idolization of death which is prevalent among us today."

I conclude from this that unless a true and effective proclamation of the resurrection is renewed in the churches, the hole in our culture will not be filled and we will find that we are much nearer the end of history than most of us care to imagine. Easter is before us. That proclamation is still possible. The requisite graces for making it effective are still available. But will we seek them? Will we receive them? That is the question. If not, we must leave to Cohen the last word:

Your servant here, he has been told

to say it clear, to say it cold:

It's over, it ain't going any further

And now the wheels of heaven stop

you feel the devil's riding crop

Get ready for the future:

it is murderWhen they said REPENT REPENT

I wonder what they meant

The churches in my neck of the woods have been a huge disappointment during these two years of fright stoked by a worse-than-average flu. Even now, when secular authorities have dropped the odious vax passes, a local Protestant church refused entry to a concert to those who could not show proof of having been injected with the harmful, ineffective "vaccine."

About ten years ago, after a period of atheism, I slowly returned to faith in God, the writings of St John of the Cross being very helpful in setting me straight. Coincidentally, my parish bulletin announced that Frs. Laurence Freeman and Richard Rohr would be holding a weekend conference on Christian contemplation. On the last day, during a Q & A session, Richard Rohr announced--unprompted--that he did not believe in the "supernatural Jesus," a sentiment enthusiastically seconded by Fr. Freeman. Goodbye, miracles and Resurrection! Hello, CS Lewis' madman!

Hello Douglas.

Would this be helpful?

“Theology mediates between a cultural matrix and the role of religion in that matrix” B. Lonergan

Or not?

++++

I’m trying to understand your multiple references to Tao (or Dao in pinyin) as per Lewis. Going from memory, I recall Tao not being primary. “Humans are patterned after Earth, Earth is patterned after heaven, heaven is patterned after Tao, and Tao is patterned after self-evidencing”. It’s been 30 years since my study of ancient Chinese but this is top of mind. As you know, Chinese is quite connotative but my point remains: Tao isn’t primary.

I have another question regarding ontology but need more time to think it out. The main point here is, could we not put ontology aside for a moment and deal with nominalism via epistemology? I’m taking a risk here putting it so boldly.