source

Note to the reader: At the end of part two of this series I made the counterintuitive claim that the doctrine of original sin had some bearing on the prospect of an effective political resistance comprising libertarians and traditionalists. In the light of things considered here, that may seem a rather trivial concern. But it is Holy Week, which together with Purim reminds us that even our trivial affairs are caught up in a great struggle. The better our understanding of that struggle, the firmer our resolve to resist.

Who, seeing that the capacity for reason distinguishes man from other animals, will dispute the claim of Leo in Libertas that “the end or object, both of the rational will and of its liberty, is that good only which is in conformity with reason”? And who, recognizing that reason sends us in search of this good, will doubt that we need virtue in the pursuit? Who will question that submission to the Source of all good is indispensable to any successful search, or imagine—if all is not in vain and reason itself unreasonable—that true virtue can exist without religion of that sort: the religion not of fear but of faith, not of greed but of gratitude?

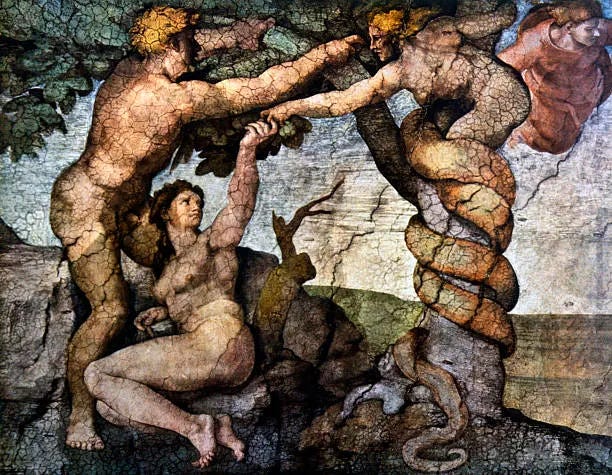

The serpent will. For the serpent is a contradiction in terms, an irrational animal with rationality and the power of speech. It takes contradiction as its proper work. It contests the command of God. It questions the motives of God and so implies that God himself is conflicted. It makes disobedience the true virtue. It leaves no place for gratitude. Just so, it alienates man from God and man from woman and man from man. Those who heed its call to liberate themselves find themselves enslaved.

The serpent is not a feature of creation, essential to the unfolding of the story of creation. If it were, reason would have to posit self-contradiction in the Creator, and so also in itself. Reason would be defeated before it began its own work, and even Hegel could not save it. No, the serpent is an anomaly, an impediment to creation that inexplicably appears within creation.

Whence comes this anomaly, this accuser of God before man, this adversary of man before God, this defiler of conscience who substitutes false reasoning for true, making excuses in sins? Having read Moses with more humility, a repentant Dostoevsky got right in Karamazov what proud Hegel got wrong in Philosophy of History. Making excuses in sins is what the serpent is all about. Making excuses, sometimes very clever excuses, is its most basic reflex. And sin, of course, precedes and follows every excuse for sin. No sin and no sinner, qua sinner, comes from God.

The serpent’s true origin and identity is gradually disclosed as the narrative develops. The serpent is Lucifer, that once marvelous creature in whom created goodness and greatness, having shone forth in the dawn of time, were corrupted by a perverse turning of the will. The serpent is that image-bearing agent who first treasonably abused his liberty, making of himself a contradiction. Hence he is called “Satan” and “Belial.” He it is who has seduced man to do the same; though it is perfectly evident, as Leo says, that “any liberty, except that which consists in submission to God and in subjection to his will, is unintelligible”—mere hissing, to which meaning is falsely ascribed.

This hissing, alas, is not for the purpose of warning the prey away, that the serpent need not strike. It serves rather to distract until it does strike. It is designed to obscure the fact that God is the source of faith, as of reason; the source of liberty, as of law; the source of joy, as of justice. These are not antitheses in search of a synthesis. They are not contraries but correlatives. They do not need to be reconciled by us; we need to be reconciled by them.

“Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom,” rejoices St Paul. Which is why, when driven by the Spirit out into the desert beyond the life-giving river, when sent out of the garden not for sin but in pursuit of sinners, when encountering the self-same serpent slithering among the dry sands and baking rocks of our freedom falsely so-called, Jesus did not flinch but remained absolutely steadfast. He was able to look the serpent in the eye and rebuke it. The hissing, for a moment, stopped.

The tempter tried this time a different tactic: affirming the word of God rather than questioning it; making himself out to be the agent of God; offering to mediate the worship of God. All to the same end, however, and by the same means, the treasonous abuse of both language and liberty.

He was no match, however, for the Son of God, whom in the hearts of men and the affairs of man he hoped to supplant. The Son was faint with hunger, voluntarily suffered. He had made himself weak, as we are weak. Satan could carry him away, light as a feather, to the pinnacle of the temple on Zion and to the pinnacle of that anti-Zion from which he seeks to rule all the kingdoms of men. But he could not carry him off into his own idolatrous disobedience, or induce in him any paralysis of despair. For the Son had not come in the freedom and power of the Spirit of God to destroy the law of God, but to fulfill it. He had not come to follow the serpent but to silence the serpent. He had come to make reason reasonable again and man free again.

Like Moses, who fasted forty days on the heights of Sinai, Jesus returned from his wilderness fast to instruct the people of God in the ways of God. “You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free.” He then accomplished in fact what Moses and Aaron had accomplished only in figure. He defeated those great contradictions, sin and death. He subjected man to the judgment of God that man might see the salvation of God. He made it possible for the hissing serpent to be silenced forever.

The serpent had turned the tree in the centre of the garden, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, into an ugly pole for painful death. Jesus turned that ugly pole into the very tree of life, “that he who overcame by a tree, by a tree also might be overcome.” Laying down his own life before Pilate, as Aaron had symbolically laid down his staff before Pharaoh, Jesus destroyed a whole brood of serpents. He swallowed up sin and the consequences of sin. He swallowed up the last enemy, death. He disarmed the hostile powers, visible and invisible. Having demonstrated the coherence of freedom and obedience, having walked as man the path of communion with God, he received for man the salvation of God. He reopened the path to paradise, even for the man on the pole next to him—the one who, however belatedly, began to walk it—and brought into view for all men the way to God himself.

The doctrine of the fall asserts that the first humans, though made straight by God in the beginning, afterward, by listening to the serpent, made themselves crooked. The doctrine of original sin asserts that each subsequent human, as the offspring of sinners, inherits a nature bent by sin, a nature no longer enjoying its proper rectitude. Each therefore suffers from a propensity to sin, as from sins actually committed, whether his own or another's. Each also bears his share of the guilt that attaches to this condition.

The former doctrine is based on revelation. The popular evolutionist, whose quite different doctrine prevails today, dismisses it as fanciful. According to him, there never were any first humans, just any number of brutes in various stages of transition. How there came later to be something properly human is rather a mystery, one into which we ought not to pry too deeply. For in this myth there are neither beginnings nor endings. There are no distinct kinds and no fixed boundaries. One thing, given sufficient time, gradually becomes another thing; sufficiently often, a better thing. And so there is light, there is progress, though it is unclear how it begins or what keeps it moving or where it leads. Chesterton's aphorism in The Everlasting Man captures well enough the hidden pessimism beneath the surface optimism of this alternative. “Evolutionism: the idea of creatures constantly losing their shape.”

Now those who hold to this myth or, if you prefer, to this philosophy—we must not say “to this biology,” for biology is insufficient to account for the human—are bound to dismiss the doctrine of the fall, which posits an Artist, a well-made image of the Artist, and a rebellion of the image against the Artist. Such notions are said to be both fanciful and vainglorious, as is theology, the discipline that purports to deal with them. Man is a particularly clever animal, a somewhat elusive animal with an almost miraculous form of consciousness, but no more than an animal. The tale of his catastrophic fall is a mere saving of the appearances, a way of accounting for what Kant called the crooked wood of our humanity and for the cleverness with which we harm ourselves or others.

The doctrine of original sin, however, is another matter. For even the most optimistic evolutionist admits that the wood is indeed crooked. Original sin is a doctrine, says Chesterton, that anyone, the stubborn atheist included, can prove. Indeed, it is the church's only such doctrine, apart from the existence of the Creator himself, which the church holds to be self-evident. Scoffing at the unprovable doctrine of the fall does not disarm the provable doctrine of original sin, though it changes considerably its complexion. Nor does it dispose of the need for a remedy.

What will the remedy be? The first remedy proposed is what Lessing in 1780 called the education of the human race. The second is what Galton in 1883 called eugenics. Their proposals are different, since one begins with the mind and the other with the body, but they have this faith in common: providence will see to a remedy, though there be no provider; redemption will come of it, though there be no redeemer; the crooked will be made straight, though there was never any straight that was made crooked.

Very optimistic, that! Yet also pessimistic to the point of despair. Its Manichaean element is even more pronounced than its Pelagian. For original sin, it turns out, is not bound up with the fact that we are moral creatures, creatures (as the theologian would say) made in the image of God. It is bound up with the fact that we are made of mud and clay. The future, then—that better future towards which we must look in hopes of a remedy—can only be approached by paring away the past, by scraping off the mud; not only the mud from which we were made but the mud we ourselves make. We must sweep away all those traditions by which we have been preserving the past.

What is at stake in this war of soteriologies, this contest of ideas about sin and salvation? One thing at stake is the scientific endeavour to understand man and his world. That endeavour owes its very soul to the Christian tradition, which is decidedly anti-Manichaean. Its condition of possibility is the creatio ex nihilo dogma and the credal affirmation of the goodness inherent in all things visible and invisible. It draws its life-blood from faith in the divine freedom to effect creation. Its DNA is confidence in a creaturely order governed by contingent but intelligible laws that man may explore in freedom. Its conscience is the conviction that there is a real distinction between truth and error, and that putting forward error as truth or truth as error—the simonious habit of our scientific journal industry—is wicked.

More importantly, man himself is at stake. The biblical doctrine of the fall, which is premised on the special creation of man and on the unity of the race, is no more a product of pre-scientific naïveté than is the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo. As the latter made possible a worldview in which experimental science could flourish, the former made possible a defence of man against those who would eventually reduce him to an object of experiment. That defence is disappearing with the doctrine of the fall and its attendant concept of original sin, which speak for, not against, the stupendous dignity bestowed on the creature made concordantly of mind and mud. The glory granted man when he was moulded by the two hands of God, the Word and the Spirit—the glory defended in person when those same hands wonderfully restored him through the incarnation, giving him a new and surpassing glory—is fading from our view.

There are those today who say that man has no definite nature to be defended; that there is nothing stable in man that can serve as the vessel of his dignity; that they may therefore do with man whatever they wish, moulding and remoulding him to the requirements of their own economic or political models, which they dishonestly label “scientific.” They have already been shown to be liars, like their infernal father. By virtue of man’s surpassing glory, however, and by reason of the contest they are in, they have had to spin out ever larger and more impressive lies.

Their first move, subsequent to the defeat of Manichaeism, was a philosophical attack on “kinds.” (Anselm was already onto that a thousand years ago, as I explained in Theological Negotiations.) Their next move was to trade talk of a God-man for talk of a man-God. The former comes suddenly and decisively, from the womb of the virgin, to crush the head of the serpent. The latter comes slowly, from the womb of history, to join with the serpent. God does not become man that men might become gods for all eternity. Men become gods that God for a time might become man.

Thus, they aver, is the mystery of consciousness solved. Consciousness as potency actualizes itself by manifesting itself to itself through man. After that, who knows? Experimentation has already begun. Consciousness is breaking free from the constraints of nature, even of human nature, and from all that circumscribes or pre-determines it. Consciousness is freeing itself through man and from man. It is displaying its divinity, its miracle-working power. It is not consciousness that is artificial, but “man” that is artificial.

Modernity, as D. F. Strauss confessed, posits as many miracles as does the creed, even the same miracles. It just posits them more palatably by factoring in vast amounts of time and by making man, or consciousness working through man, the miracle-worker. It has time itself as the instrument of our deification, history as our redeemer. We must not waste time looking backward to some supposed fall and redemption found in biblical fables. There lies darkness; the future is the right side and the bright side of history.

Those who speak of an historic fall and an equally historic redemption, as Troeltsch observed, contradict “the idea that lies at the foundation of all modern thinking—a development of spirit which emerges at different nodal points from the depth of the divine life, and a possibility of future developments which can never be circumscribed in advance.” Otherwise put, they blaspheme against the cult of progress. They make themselves an impediment to progress, especially if they also look forward to one coming suddenly from the womb of heaven to judge the quick and the dead. Talk about circumscribing in advance!

These contrarians, of course, these obstructionists, are the same people who believe in created order. They cling to quaint institutions, such as the natural family, and to outdated notions about the inviolability of marriage and the sanctity of the home. They speak with Leo of private property as a fundamental right, of freedom of conscience and religion as non-negotiable. They demand that science be truthful and refuse to bow to idols erected in the name of science. They are dangerous reactionaries, disturbers of the peace.

There are too many of them, hisses the serpent, and they have become a threat to progress. They have not grasped the greatness of the eugenic enterprise, the tidying up from all that mud through which consciousness has hitherto slithered, even if they have grasped what colloquially is called “cleaning up.” That is, they don't see the need to eliminate the weak and the useless, to destroy life unworthy of life, even if they do see the link between the inevitability of progress and the fact that certain men must profit from progress.

Neither, then, do they understand the necessity of the modern interventionist state. They fail to recognize the nodal point at which we have now arrived. It is, to borrow their own language, a lenten point. It requires a yielding up of individual rights and freedoms, even a yielding up of the self. It is a point of transition from the age of the enlightened individual to the age of the Saviour State, the state that knows "when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise up," the state whose dictates are bound to the forehead and stitched to the hem.

Something must soon be done. Such people, whether they call themselves libertarians or traditionalists or simply Christians, are intolerable because they insist that God precedes and dignifies man, and that man precedes the state, which must respect his dignity; that a man possesses an a priori right to provide for himself and to govern himself under God. They insist on a liberty that can no longer be granted them.

source

Our Jewish brethren have just celebrated Purim. The story of Purim is that of Haman, who had himself decided that something must be done. Or rather it is the story of Mordecai and Esther, who knew that something had to be done when something was about to be done.

Haman’s motives were the same as the serpent’s. He was puffed up with pride. His pride turned to jealousy and resentment, and his resentment to fury. The immediate object of his fury was Mordecai, a Jewish exile who would not bow down before him despite the fact that he, Haman, was second in the kingdom of Ahasuerus, second in the empire of Artaxerxes the Great that stretched from India to Ethiopia. Haman hatched a plot against Mordecai and his people, against all the Jews in the land. To the king he said:

“There is a certain people scattered abroad and dispersed among the peoples in all the provinces of your kingdom; their laws are different from those of every other people, and they do not keep the king’s laws, so that it is not for the king’s profit to tolerate them. If it please the king, let it be decreed that they be destroyed, and I will pay ten thousand talents of silver into the hands of those who have charge of the king’s business, that they may put it into the king’s treasuries.” So the king took his signet ring from his hand and gave it to Haman the Ag′agite, the son of Hammeda′tha, the enemy of the Jews. And the king said to Haman, “The money is given to you, the people also, to do with them as it seems good to you.”

Now, the timing of this plot was chosen by Pur; that is, by divination, a detail worth noting. The king didn’t know about that, nor did the letter that went out to the realm mention it. In diplomatic fashion, it described Haman as a man excelling in sound judgment and distinguished for his “good will and steadfast fidelity.” None should question his judgment; and the justification it supplied for what he had judged necessary—for the well-financed, state-sanctioned violence—was that the target population had to be destroyed for political reasons. They were, it said, a “hostile people, who have laws contrary to those of every nation;” a disobedient people, “ill-disposed to our government, doing all the harm they can so that our kingdom may not attain stability.”

When the decree of intolerance (that is, of mass murder) was promulgated, Mordecai went to Esther, who by divine providence was Ahasuerus’s new queen, and begged her to intervene. Her reply? “Hold a fast on my behalf … and I will go to the king, though it is against the law.” Which Mordecai did, reminding the King of the Universe that he had aroused Haman’s wrath, not out of his own pride or resentment, but out of faithfulness to the covenant. He had refused to bow down before Haman, not because he detested the detestible, but lest he “set the glory of man above the glory of God.”

The whole story, which I trust the reader recalls, is about the glory of God, because it is about the faithfulness of God to those who remain faithful. Esther and Mordecai prove faithful. Like Daniel and friends, they know which King to turn to first, just as they know whose law comes first and must be put first. They know who the real King of Glory is. Hence, though they are frightened by the serpent, they are not fooled by the serpent. Though they are afraid of Haman, they are not bested by Haman. With God’s help, his plot is foiled. He is deceived by his divination, destroyed by his own devices, dispatched on his own derrick. For the people of the Lord cried to the Lord, and the Lord heard them and delivered them out of all their troubles.

The Lord also gave them a role to play in their own deliverance, as he gave Haman a role to play in his own destruction. The law of the Medes and Persians being what it was—fixed and irrevocable: a pagan likeness to the law of God—the sword that had been set against them by the decree of intolerance could not be withdrawn. But a sword could be put in their hands, too, a sword with which to defend themselves, and that sword prevailed. The fear of God and of the people of God fell on all the nations, even on the king, who, having repented of the evil that was to be done, prevented it from being done.

The deuterocanonical version of this story, and this too is worth noticing, decks it out with apocalyptic features. Mordecai has a vision and, in his vision,

behold, two great dragons came forward, both ready to fight, and they roared terribly. And at their roaring every nation prepared for war, to fight against the nation of the righteous. And behold, a day of darkness and gloom, tribulation and distress, affliction and great tumult upon the earth! And the whole righteous nation was troubled; they feared the evils that threatened them, and were ready to perish. Then they cried to God; and from their cry, as though from a tiny spring, there came a great river, with abundant water. Light came, and the sun rose, and the lowly were exalted and consumed those held in honour.

This is the language of the prophets, the language taken up also by Jesus in the Gospels and by John in the Apocalypse. It is language for today. “Noise and confusion, thunders and earthquake, tumult upon the earth!” Do we not hear it on the streets, see it on our screens, feel it in the air? Something is about to be done.

The dragons are said to be Haman and Mordecai. One might suppose today that they are Hamas and Israel, whose conflict reverberates around the globe. That is not how John has it, however. His dragons do not fight one another; they form an alliance in which both fight against the faithful. That is a still more disturbing possibility, of which I have spoken elsewhere. What I want to say here is that we are not dealing with Ahasuerus or with the kingdom of Ahasuerus. We are not even dealing with Nineveh and the king of Nineveh or with Nebuchadnezzar and the kingdom of Babylon. They may repent and divert disaster, at least for a time. The empire with which we are dealing will never repent, for it is impenitent by nature. It deals in the inevitable and, for the inevitable, as Chesterton says, there can be no repentance, because there can be no accountability.

This empire is not like that of the Medes and Persians. It makes law without respect for the limits of law. It multiplies anarchically its commandments and decrees. There is nothing it will not regulate and no regulation it will not change at its whim or pleasure. There is nothing sacred it will not mock and, if possible, annihilate. It has murder in its heart, as is plainly attested by the fact that it has made abortion its icon. The man who supposes that its murderous intentions will stop there is a fool. The man who thinks the tumult and madness, the frenzy of self-destruction, is merely a passing fit deceives himself. The serpent has already struck. The venom is in the veins. And there is no antidote in science or politics, there is no salvation without the sword.

This empire must nevertheless be confronted. It must be confronted with the resolve of Mordecai, the courage of Esther, the determination of Daniel. Both the Jew and the Christian, who must not fight each other, require that resolve. So do the libertarian and the traditionalist, whose political differences should be set aside. It is past time to see through the conceits of secularism into the heart of the beast. It is time to look the serpent in the eye.

But which sword should be raised against it—the sword of self-defence or the sword of the word of God? The book of Esther maintains that the two are compatible, that both have their place. Who can disagree? (Let him who disagrees consult Solovyov’s last book, in which is no mean metanoia.) But there can be no doubt which is the essential weapon and, in truth, the only really effective weapon. It is the one Jesus himself used in the wilderness, rather than the one Peter used in the garden.

source

Something must be done! That’s what the rulers in Jerusalem said when Jesus told his parable of the vineyard, for they too (though not all of them) were past repentance. And something was done, something appalling, something very like what he had predicted in the parable.

The Triduum is again upon us. Good Friday approaches, when we remember just what was done, which men meant for evil but God for good. Easter follows hard on its heels, in celebration of the great victory over evil and of the dominical admonition based on that victory, “Fear not!” These rituals prepare us for the future as for the present. They prepare us for what is yet to be done at the close of the age. They are not merely the re-enactment of a meaningful myth or the rehearsal of an inspiring legend.

Whatever is made of the book of Esther, it is a fact of history that Jesus was crucified under Pontius Pilate, that he suffered death and was buried. It is a fact of history—nay, a history-altering fact—that he rose from the dead, in accordance with the scriptures, and was seated like Mordecai as second in the kingdom. Not the kingdom of Ahasuerus, but the kingdom of God Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, who said to him: “Sit at my right hand, till I make your enemies your footstool.” Thus did God remember his people and vindicate his inheritance. Thus did he rescue the Jews and redeem the Gentiles in the bargain.

A virgin besought God, or rather God besought the virgin. A man in distress turned to God, only to discover that God had already turned to man and become man. The man God became was placed under an edict of intolerance, condemned to death by a plot in high places. Better, it was said, that one man should die for the people than that the people, in their enthusiasm for him, should bring down the wrath of Caesar. But the plot was known to its target and the tables were turned, after first being overturned. The plotters did with the money (just thirty shekels) and with the people (who proved quite pliable) what seemed good to them, and Pilate washed his hands. Yet things did not go as planned. There was that business about the empty tomb, about the stone that had become lighter than a money-table and just as easily manipulated, despite the security guards. In the end the wrath of Caesar fell on them anyway. They had only been erecting their own crosses, just as Jesus had warned.

In the light of this history, and of this disastrous fall, the primeval fall recounted by Moses is known to be history as well, though it be dressed as legend or myth. The predictions of the prophets are taken with complete seriousness, though they be couched in apocalyptic language; the predictions of Jesus likewise, though often couched in parables. The age is not yet over, the saeculum is not yet closed. But it will be. That he said quite plainly.

Those who know what needs to be done when something is about to be done will see to their own repentance. They will call their neighbours to repentance also, lest their neighbours remain unarmed. For as it was in the holy city, so shall it be in the whole world. The serpent still hisses in Susa, though by faith it has already been foiled. It remains a contradiction in Jerusalem, though by the cross of Jesus its head has been crushed. It brings noise and tumult upon the earth, writhing with pain and fury, for it has lost its prey and its eternal fast is about to begin.

Who has exposed its plot? Who has made a way of escape? Who has arranged that the penitent should find a path to paradise and that the impenitent should meet with justice, justice that will come swiftly in its time? That One will cut the serpent’s head clean off, like Judith slaying Holofernes. “Do not think that I have come to bring peace on earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.”

The serpent has been hissing nearby, from the tent city that is about to be removed from McGill. A journalist friend was taking photos yesterday when he was asked to stop by some bright young thing who said it made her feel unsafe. Came the reply from my friend: "You're calling for global intifada and you're worried about feeling unsafe?" Well, yes, apparently. Neither facts nor logic seem to register any more. But here's someone for whom they do register: https://thenewconservative.co.uk/this-is-no-genocide/

I received through the post (not unhelpful) material reminding me of the atheistic assumptions of some libertarians and of Ayn Rand in particular, though Rand did not consider herself a libertarian. It should go without saying that the coalition I was calling for in part two could not extend so far as to include the likes of Rand. I do not regard Rand as a lover of liberty any more than I regard Lucifer as a lover of liberty; and that, as I said in part two, is essentially what I mean by "libertarian," though next time I will have a bit more to say to those who wear the label in a more technical sense.