The Violent Seize it by Force

Reflections on John the Baptist, Part II

Caravaggio

Read or review Part I here.

Herodias, who loved soft raiment and hard power, took still more exception to John’s rebuke than did her new conjoint, Herod Antipas. She eventually found just the right moment to arrange for the dissociation of John’s head from his neck and a public display of his offending tongue. Her daughter, Salome, proved of some assistance, even if, as in Caravaggio’s painting, she turned her own head from the sight.

How do people arrive at this condition, cooperating with evil, doing evil, persisting in doing evil while averting their eyes from the obvious effects of evil? Our rulers today, by and large, are such people, as are many of us. Malachi 3 provides the answer. They say to themselves, “It is vain to serve God. What is the good of our keeping his charge or of walking as in mourning before the LORD of hosts?” And then they find other masters to serve, if at first only their own passions or love of prominence.

John had come to them, eschewing even priestly power, wearing a hair shirt and eating bugs, calling them to mourning and repentance. Some responded rightly, in his day as in Malachi’s, and received the divine reassurance. Malachi 3 again:

Then those who feared the LORD spoke with one another; the LORD heeded and heard them, and a book of remembrance was written before him of those who feared the LORD and thought on his name. “They shall be mine,” says the LORD of hosts, “my special possession on the day when I act, and I will spare them as a man spares his son who serves him. Then once more you shall distinguish between the righteous and the wicked, between one who serves God and one who does not serve him.”

Others responded wrongly, not thinking on God’s name at all, hence failing to make the distinction in question. There were those, to be sure, who were still looking for the redemption of Israel, but it was merely a political solution they were after. In John’s day, that meant liberation from Rome. When John went to prison and the banks of the Jordan were no longer teeming with crowds, it seemed to them that he had not panned out politically. So they looked elsewhere.

Mark tells us that “after John was arrested, Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of God and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent, and believe in the gospel.’” He did many miracles in support of this gospel, and he did not wear a hair shirt or eat bugs. But Jesus didn’t pan out either, politically speaking. The commoners were prepared to make him king, by force if necessary, but he would not have it, not on their terms. The chief priests and other members of the establishment in Jerusalem wouldn’t hear of it on any terms. Incited by men in soft raiment, a crowd of commoners was soon shouting at Pilate, “Crucify him, crucify him!” Reeds, shaken by every passing political breeze, caught up in an imponderable evil because they would not ponder the things of God.

And we, are we not as indeterminate as they and as capable of evil? The gospel of the kingdom, which Jesus took up from John, has gone out into all the world, just as he said it would. But we who have benefited from it, who have even helped convey it, have lost interest in it. We no longer think on the name of God or contemplate the Christ whom he sent.

Suppose that François de Laval – he who abandoned a family fortune in old France to evangelize New France, who slept on a slab and wore a hair shirt under his episcopal raiment – were to reappear in some remote place along the St Lawrence. Would the people of Quebec City or Montreal bestir themselves to go out to him? Would they listen to him if he preached repentance for their materialism, their sexual sins, their culture of death, their unreadiness for the return of Christ? If they did begin to listen, how long it would take the chief priests in the Citadel to muster the courage to arrest Laval for praying in public?

Or suppose that miracle worker, Brother André, were to reappear. When he died on Epiphany in 1937, a million people filed past his coffin in Montreal, a city then boasting a population of little more than 800,000. Less than a century later, barely fifteen percent of Montrealers are regular church-goers. People still queue for miracles, yes, but what sort of miracle? Not the sort that is remedy for both body and soul. Our chief priests would know how to deal with Brother André if he failed to understand the new Quebec. With delicious irony, they would declare a Public Health Emergency, forbidding the people to go anywhere near him, instructing them to queue instead for the magic of Science.

I am not writing, however, to elaborate on the greatness of a seventeenth-century bishop in partibus infidelium, or of a miracle-working church doorman of the early twentieth, or for that matter on the gullibility of hoi polloi in the twenty-first. It is a first-century prophet in Israel of which I am writing. And I am writing of him because we have forgotten him, too. Having no longer any comprehension of his true greatness, or of our own impoverished condition, we in Quebec make a special point of forgetting him on every St Jean Baptiste Day.

Let us pick up, then, where we left off in Matthew 11. John, in the paragraph we were considering, had questioned Jesus. Was Jesus really the one through whom God would act, on the day that he acted? Jesus, having sent back to that honest man an honest report of what God was doing, turned to question the crowds about their attitude towards him and their motive for having gone out to hear him. He confirmed for them that John was a prophet, and more than a prophet. He identified him as the messenger of the last days about whom Malachi had written. And now, in our next paragraph, he heaps further praise on him, quite startling praise.

Truly, I say to you, among those born of women there has risen no one greater than John the Baptist; yet he who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he. From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and men of violence take it by force. For all the prophets and the law prophesied until John; and if you are willing to accept it, he is Elijah who is to come. He who has ears to hear, let him hear.

To make sense of this paragraph is still more challenging. No one greater born among women? Among the sons of Adam none who could be said to be his superior? What of Abraham, of Moses, of David? And what does Jesus mean by saying that John is Elijah, whom John denied being? What is this business about the violent seizing the kingdom by force?

John as Elijah (and Elijah as John)

Let’s start with that last question and work backwards. “From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of the heavens (ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν) suffers violence (βιάζεται) and the violent (βιασταί) seize it by force.”

We may take this narrowly, as a reference to the arrest of John and to a growing harassment of his disciples and of the movement now centred on Jesus. John declared that the coming of the kingdom was imminent and by his actions (as N. T. Wright observes) he implied that the existing institutions in Israel would not suffice to receive it, nor indeed survive it. The covenant people must repent and begin all over again. They must return to the desert in a new exodus. This was upsetting to the authorities in Jerusalem and to everyone invested in the status quo, whether the Pharisees or the Sadducees or the Herodians. It was upsetting to parties on the fringes also, such as the Zealots, and those who advocated revolution. None of these were looking for repentance. All were looking for power, though their strategies for gaining power, or preventing others from gaining power, differed.

But we may also take it more broadly, for with the appearance of John a whole history of struggle for the kingdom had come to a head. The days of John, we may say, taking our cue from “born of woman,” were the days that began when Cain slew Abel and founded the first sanctuary-city as a fortified substitute for Eden. They were the days when the Nephilim were upon the earth, projecting power far and wide, in league with thrones and dominions in rebellion against the heavens. They were the days in which the sons of Cush, who were migrating from the East, “found a plain in the land of Shinar” and set about building Babel in hopes of recapturing Eden. They were the days of the great empires of the Mediterranean basin, from Egypt to Babylon.

In Israel, they were the days of the sons of Korah, the days of the sons of Eli and of the Philistines, the days of Jereboam and of Ahab and Jezebel, who seized the vineyard of Naboth. They were the days of Antiochus, who styled himself Epiphanes, whose collaborators in Jerusalem the Maccabees overthrew. They were the days of the late Hasmonaean dynasty and of Herod the Great, who turned the temple in Jerusalem – God’s own humble analogue to Eden that Antiochus had violated – into a wonder of the world so that Herod himself might seem a worldly wonder: the same Herod who placed a golden eagle over the temple gates as a sign of allegiance to Rome, the empire to end all empires; who also slaughtered the innocents in Bethlehem in hopes of preserving his own power and glory against the coming of the Christ.

They were the days, in other words, in which those charged with tending the garden of God, that it might yield the fruit of righteousness, tried rather to make it their own private possession or sell it to the highest bidder – the days that must lead, as every genuine prophet had insisted, to the outpouring of the wrath of God. They were the days John had in mind when he espied those coming from the temple authorities and cried out: “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?” They were the days of which Jesus, weeping, warned.

On this broader view, of course, they are also the days in which we ourselves live, so long as we live in opposition to God and his Christ, wresting the gospel of the kingdom to our own ends, trying in vain to reverse-engineer Eden for our own possession. They are the days of reformations that do not reform, of enlightenments that do not enlighten, of revolutions that bring no relief, of liberations that only enslave. They are days of war and rumours of war, of genocides and accusations of genocide, days of a perpetual want of peace. They are days in which secularists and socialists dream of a kingdom God cannot touch, a kingdom that knows no heavens above, no thrones or dominions but man’s own: a kingdom in which all is ordered by human “science” and everything permitted that man in his arrogance wills to permit. They are days of violence indeed, days in which the innocent and the vulnerable are handed over to Moloch, while the poor, as ever, are trampled into the dust. They are days of traditores in the Church, who hand over to profane men the holy things of God, days of trading in children for the lusts of man, or even in body parts. They are days of technological prowess detached from any moral underpinnings, days running to disaster, days that unless shortened by God no flesh would survive.

We need not choose between the narrower reading and the broader. Both set the stage for Jesus’ further deployment of Malachi, which we need now to notice.

In chapter 4, Malachi identifies the messenger of chapter 3 as none other than Elijah. “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes.” Jesus, therefore, who has identified the messenger as John, must also identify John with Elijah. John, he implies, takes up Elijah’s struggle with Ahab and Jezebel, in the persons of their epigones, Antipas and Herodias. He takes up his lonely contest with the bloated bureaucracies of Baal and Asherah, for so he viewed οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι, the rulers in Jerusalem. He takes up Elijah’s quest for the hearts and minds of the people, urging them to cease their vacillation and declare themselves. “How long will you hobble along on two contrary opinions?”

John, moreover, having offended Herod – “that fox,” as Jesus called him, upon hearing that he himself was on Herod’s hit list – suffers the fate Elijah feared to suffer but did not suffer. And John, like Elijah, presides at a great theophany, of which we will speak shortly. In all this John prepares the people for the day of the LORD, that fateful day of division which Malachi describes thus in chapter 4:

For behold, the day comes, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble; the day that comes shall burn them up, says the LORD of hosts, so that it will leave them neither root nor branch. But for you who fear my name the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings.

John was not just any prophet. He not only spoke of these things but precipitated them. And with John came Jesus, who claimed the presidency over them. John went before him sounding the trumpet, recalling the people to the law and to the God whose law it was. “Remember the law of my servant Moses, the statutes and ordinances that I commanded him at Horeb for all Israel.” For those who could accept it, John was indeed Elijah. “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes.”

There were differences, naturally. Elijah, after preparing an altar for the Lord with the stones of Mount Carmel, dug a trench around it and baptized it with water, that the fire from heaven might display its power by licking up even the water. John prepared an altar of living stones, down among the desert sands, through a baptism of repentance, that they might be cooled against the fire. The he baptized the Fire itself. John was a prophet and more than a prophet. He was Elijah and yet not Elijah, as Jesus explained to the inner circle of his disciples on the slopes of Mount Tabor.

Peter, James, and John had enjoyed there a private viewing of the foundations of the kingdom. They saw Jesus conversing with Moses, through whom came the law, and with Elijah, the prophet most like Moses. They heard the Father’s voice, repeating what it had said publicly, in the presence of John, about Jesus being the beloved Son. They saw Jesus standing before them, not as he stood before John in the humility of his baptism, but robed with majesty and girded with strength. Afterwards, Jesus explained to them what he had only alluded to earlier; that is, in Matthew 11. “Elijah,” he said, “does come, and he is to restore all things; but I tell you that Elijah has already come, and they did not know him, but did to him whatever they pleased. So also the Son of Man will suffer at their hands.”

The typologies in play are obvious enough, perhaps, but the prophetic scheme warrants further clarification. We may put it thus: Just as the whole act of creation, from start to finish, is conveyed by Moses in poetic form as transpiring in a week of days, so the whole of human history, from beginning to end, is concentrated by Jesus into a week of years located in the midst of history. From the beginning of the preaching of John the Baptist to the crucifixion of Jesus the Christ, the whole is shown for what it is and what in the end it will be. And the two through whom the showing is achieved – John and Jesus – are not βιασταί (biastai). They are not men who seize, but rather men who are seized.

John, like all the prophets before him, is seized by the need for repentance. Jesus is seized by the need for redemption, without which repentance would be in vain. Both are seized by the Spirit of God, and seized in turn by those who blaspheme the Spirit, who therefore cannot tolerate men who live and move in the Spirit. Both John and Jesus are put to death, but both will come again to complete their work of distinguishing righteousness from wickedness. Or rather, Elijah will come again, taking up the task John had taken up from him, which is to convert, before Jesus comes again to separate the converted from the unconverted.

That final conversion and separation will transpire in a second week of years, a week that falls, not somewhere in the midst of history, where history pivots towards its end, but precisely at its end. “There shall be no more delay!” In that week the biastai will make one last fox-like attempt at seizing the grapes of the kingdom, but they will fail. “Sit in silence, and go into darkness, O daughter of the Chaldeans; for you shall no more be called the mistress of kingdoms.”1 In that week the final lines of the book of Malachi will be fulfilled a second time: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes. And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the land with a curse.”

In the first fulfillment, John is Elijah, for those who can accept it. In the second, Elijah is John for those who have yet to accept it. Once more, but only once more, they will be asked to accept it. “He who has ears to hear, let him hear.”

None greater (save the least)

The presence of Moses and Elijah at the transfiguration on Tabor underscores the claim that “all the prophets and the law prophesied until John,” and that they prophesied, as he did, about Jesus.2 Moses and Elijah speak with Jesus concerning the “exodus” he is about to accomplish, for it is in the death of Jesus that the kingdom of heaven suffers the ultimate violence, and by the resurrection and ascension of Jesus that the futility of that violence is shown. The violent who put him to death suppose they are seizing the kingdom with the king, but in fact they are seizing neither. King and kingdom elude their grasp by way of the very violence they commit, and commit in the name of the law.

Storming the gates of heaven thus gets the biastai precisely nowhere, as the prophets of Baal discovered on Carmel: unless it gets them to their just reward, as Paul observes in 2 Thessalonians 1. For God will make a distinction between the wicked and the righteous, though the wicked will not. His kingdom will come with irresistible force when the Son of Man appears from heaven “with his mighty angels in flaming fire, meting out vengeance on those refusing to recognize God and to obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus.” It already comes with force whenever the wicked are caught in their own traps and made to sit in silence. Is God then among the biastai? Of course not. Force, even violent force, is not inherently unjust, nor justice necessarily non-violent. The difference between the violence of God and the violence of the biastai is the absence of justice in the latter, who exercise force to disordered ends and in a disordered way.

The kingdom can suffer violence, as every martyr knows; yet, strictly speaking, it cannot be seized by force. It cannot be seized even by desire and sacrifice, if the desire behind the sacrifice is disordered. Shortly after the epiphany on Tabor, the two sons of Zebedee came with their mother (but not with Peter) to petition Jesus for a place at his right hand and at his left when he should come into his kingdom. They knew that he was the anointed one. They did not yet understand that his anointing was incomplete, that to the water blood must be added. They were asked, “Are you able to drink the cup that I am to drink?” They thought so and said so, but were told that their petition was not in Jesus’ gift. They were then rebuked, along with the rest of the Twelve, for their inclination to seek the chief seats in the kingdom. Chief seats there will be, but they are not to be coveted; moreover, they have been reserved by the Father for those he has chosen.

In Christian art, there is a clear consensus as to those for whom they are reserved. None of the Twelve sits in them, though John son of Zebedee serves in attendance at one of them.

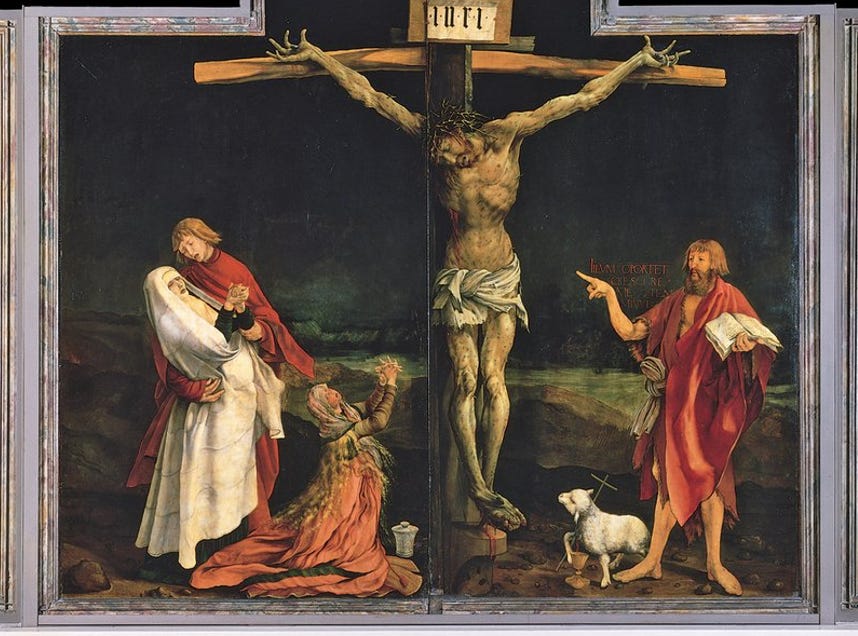

Grünewald: Mary, mother of Jesus, is at his right hand, supported by John the beloved disciple, in the company of Mary of Bethany. John the Baptizer is at Jesus‘ left, pointing to Jesus with the “prodigious index finger” of the entire prophetic tradition.

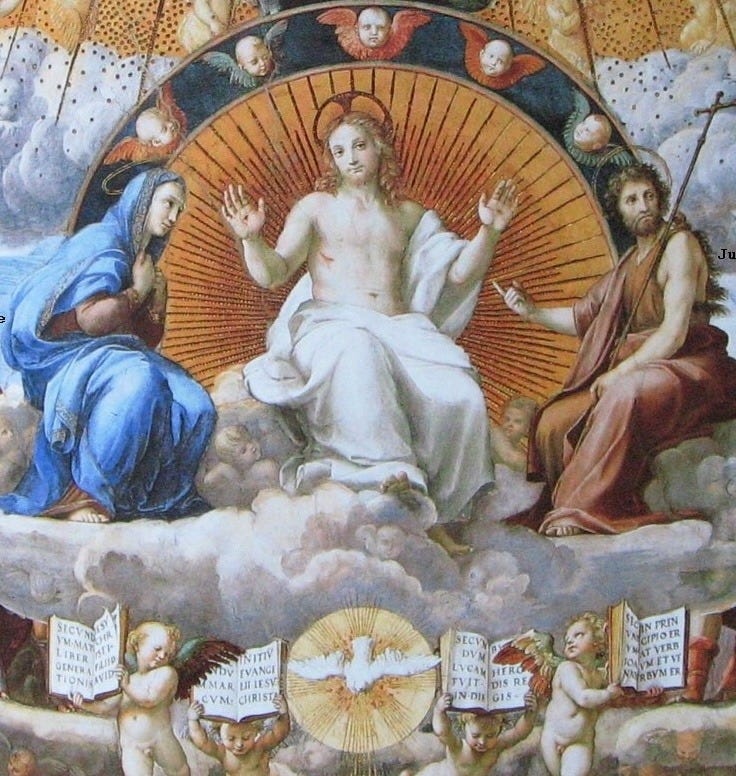

Raphael: Mary and John seated with Christ in his heavenly kingdom, to his right and to his left. (I’m not especialy fond of this painting, though I rather like its John.)

Seghers: Mary instructs the young John, who learns from her of the Spirit who will show him how to point Israel to Jesus as the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world; or, to put it differently, as the one who takes Israel’s place in wrestling with God and is smitten hip and thigh before gaining the blessing. Again, Mary is to the right (with Joseph to her right) and John to the left.

Likewise in the liturgy, where Mary mother of Jesus and John son of Zechariah (not Zebedee) flank each of those baptized into Christ. As the baptized make public confession of their sins, they do so with these words: “I confess to almighty God, to the blessed Mary ever Virgin, blessed Michael the Archangel, blessed John the Baptist, the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, to all the saints, and to you, father, that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.” Note the order. These same persons are then asked, in that order, to intercede with God for their salvation. And the priest responds for them all: “May almighty God be merciful unto you and, forgiving your sins, bring you to everlasting life.” Mary immaculate stands as witness on behalf of redeemed humanity. Michael, prince of the heavenly host who restrains the violence of the biastai, stands as witness for the holy angels. John the Baptist stands as witness that every man is called to repentance and may in fact repent.

John brings to an end the work of Moses and of all the prophets by pointing to the Saviour face to face.3 There are two who pointed before John, however, who still have some pointing to do. Elijah is one and, according to an ancient tradition, Enoch is the other. They are not exceptions to the fact that the whole line of prophets comes to its end with John, nor are they greater than John. It is just that they have not yet met their own end, but have been held in reserve, so to say, to support the work of John.4

If John is the herald of the Lord at his coming, so also are they. For they, too, announce to Israel the time of its visitation. They declare that the time for halting between two opinions has passed, that one must choose Christ or antichrist. They announce to the Jew (and the gentile with the Jew) that he must not put his hope in a city or a state constructed by man, or in any system of salvation of his own devising, but rather in God and his Christ, whose coming is at hand. The Apocalypse speaks of this in its eleventh chapter and we will have occasion to speak of it again ourselves. Just now, however, there is something else of which we must speak, if only parenthetically.

The whole line of prophets, save one?

There was another man who, some centuries after John, forsook the city for the desert, not to baptize but to pursue commercial interests and to raise a conquering army, a man many call the prophet. But this man, who presumed to resume the line that God through John had brought to an end – who presumed indeed to usurp John’s place as the one with whom it comes to an end – was the very opposite of John. John was content to decrease, that Jesus might increase. Muhammad sought to increase, that Jesus might decrease. He refused to recognize in Jesus the one whom the Father eternally loves, the one into whose hands he has given all things.

The Qur’an, in Sura IV, denies to Jesus the very thing John pointed to: his redemptive death as the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. It turns Jesus himself into an Enoch or Elijah who is whisked away to heaven, preserved from the clutches of death by not actually dying, so that in due course he may come – not to convert the Jews, but rather to testify against them. For that reason alone, we must choose between the prophetic tradition that culminates in John, who testifies to Jesus, and the religion invented by Muhammad, who purports to surpass both John and Jesus. Their respective claims cannot be reconciled.5

According to the New Testament, the child announced to Mary by Gabriel “will be called holy, the Son of God.” The one who believes in this Son, it insists, has eternal life, while “he who does not obey the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God rests upon him.” In the Qur’an, on the other hand, a spirit claiming to be Gabriel requires obedience, not to the Son, but to the messenger himself, who in God’s name has a great many demands to make. Here there is no indescribable Gift – the Word in person, found in a cradle – only another endlessly recited law, inscribed in stone. Here Marian consent gives way to raw coercion, and the wrath of man stands proxy for the wrath of God. The rivers of blood that have flowed from that moment to this bear witness.6

Let it be understood that, in the logic of the New Testament, Jesus, who comes after John, is not greater than John because he comes after him – such is the linear logic of Islam, when it posits Muhammad as the prophet par excellence; the logic likewise of “progressive” Secularism, which has been trying unsuccessfully to strike a bargain with Islam – but because he came before him. And John is not the greatest of the prophets merely because he comes after the others, but because he comes with Jesus, with the eternal Word who “became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth.”7 That Word may have been born in a cave, but it did not utter dark secrets in a cave about craven surrender or death by the sword.

So no, not the whole line of prophets save one who would come after John and Jesus: not unless we are talking about that line of false prophets of which Jesus warned in Matthew 24. There are others who come in that line, certainly, including at least one still to come. But let us not be distracted further by a religion the name of which is not Peace, but rather Submission; for that is what “Islam” actually means, as people have begun again to notice. We have something better to consider, something marvelous to consider that Islam refuses to consider, something that supplies another reason why Jesus said of John that none greater had arisen among those born of woman. Only after we consider it can we say what needs to be said about the littleness of John.

John’s unparalleled privilege

We come at the last, then, to what is really the first thing. We come to the baptism of Jesus, which stands at the head of the earliest Gospel, that of St Mark, and at the head of the last Gospel, but stands liturgically at the close of Epiphany.8 Mark, as always, is succinct:

In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. And when he came up out of the water, immediately he saw the heavens opened and the Spirit descending upon him like a dove; and a voice came from heaven, “Thou art my beloved Son; with thee I am well pleased.”

John the Evangelist, as usual, elaborates. When, in his famous prologue, the star of Bethlehem flashes down with its cosmic light to illumine the scene in which the Word has become flesh, it is this same holy theophany that confronts us.

John saw Jesus coming toward him and declared: “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world! This is he of whom I said, ‘After me comes a man who ranks before me, for he was before me.’ I myself did not know him; but for this I came baptizing with water, that he might be revealed to Israel...

I saw the Spirit descend as a dove from heaven, and it remained on him. I myself did not know him; but he who sent me to baptize with water said to me, ‘He on whom you see the Spirit descend and remain, this is he who baptizes with the Holy Spirit.’ And I have seen and have borne witness that this is the Son of God.”

The repetition of “I myself did not know him” is no editorial oversight. The Baptizer knew Jesus and did not know Jesus until God showed him Jesus. For, as Jesus declared, “no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and any one to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.” The first three Gospels all record this astonishing saying, which in Matthew appears in chapter 11, and the fourth Gospel is nothing if not its exposition. That God is, everyone knows, even if claiming not to know, for reason itself declares it. Who God is, no one can know without a revelation from God.

In postdiluvian times, that revelation came first by way of a call to Abram in Ur; that is, in the city. It came again by way of a command to Moses at Sinai; that is, in the desert. But it was perfected when the Word who called and commanded made his abode with and among us, talking in the city and walking in the desert. He came, as he told his reluctant baptizer, “to fulfill all righteousness.” He came to secure the covenant from below, as from above; from the side of man, as from the side of God. It was at his baptism by John that his mission made public, the mission he would outline in the synagogue at Nazareth. It was at his baptism that his true identity was disclosed to those who had gathered round. It was at his baptism that God’s own identity was disclosed.

There had been a hint already at the wedding in Cana as to what would come of his mission – wine from water, the wine of a new creation in which is celebrated the marriage of heaven and earth, the marriage postponed by the expulsion of our first parents from Eden. But between the old creation and the new runs a desolate road, the via crucis. Before he sets out on that road, the Son is reassured by the sound of his Father’s voice. He is empowered for his quest by a fresh anointing of the Holy Spirit. Just so, in this place and in this way, the God of the eternal covenant reveals his holy name in full. Not all have ears to hear, however. Some mumbled, as at Sinai, that they had heard only a terrible thunder. Some still do.

It was not “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” that John baptized. But it was at John’s baptism of Jesus, with the baptism of repentance before the LORD, that the triune name of the LORD was disclosed, the name in which all who desire to sit with Jesus in God’s kingdom must now be baptized.9 The entire faith of Israel, as of the Church, is bound up with that disclosure. Insofar as ears are stopped to it, or eyes averted, this faith begins to crumble. No attempt to fortify it by the elaboration of ritual or by the multiplication of theologoumena can save it. But John’s ears were not stopped, nor were his eyes averted. He, a Levite like Moses and Aaron, became the first priest of this faith by standing humbly with Jesus, the Son of God, as he offered himself back to the Father in the muddy waters of the Jordan.

“At that moment,” says Romanos the Melodist, “something happened, greater than at any moment; for at that moment the Master of the angels had come to a slave, wishing to be baptized,” and John, however reluctantly, consented to baptize him. Romanos (a Christian contemporary of Muhammad) expounds this in a fashion that joins John to Mary in the grace of consent, consent to the revelation of God and to the kingdom of God. Unlike Moses, unlike the sons of Zebedee for that matter, John does not even momentarily stretch out his hand for what does not belong to him. The greatness of his own reputation among the people does not go to his head. He confesses that he is John and only John. He knows himself a sinner, like those he has hitherto been baptizing. In the Spirit, he knows that Jesus is no sinner but the spotless lamb of God. He therefore does not see how he can baptize Jesus.

“If I perform what you command me, Saviour, I shall exalt my horn, but nevertheless I will not snatch what is beyond my power…”

“I am not asking, Baptist, that you overstep the bounds. I do not say, ‘Say to me what you say to offenders,’ nor ‘Give me the advice you give sinners.’ Simply baptize me in silence, and expectation of what will follow the baptism. Because in this way you will gain a dignity which does not belong even to angels...”

“Once Uzzah stretched out his hand to steady the Ark, and he was cut off. Now, if I grasp the head of my God, how will I not be burned by the unapproachable Light?”

“Baptist and disputant, prepare at once, not for confrontation but for ministration. For, behold, you will see what I am accomplishing. In this way I am painting for you the fair and radiant form of my Church, granting to your right hand the power that after this I shall give to the palms of my friends and the priests. I am showing you clearly the Holy Spirit, I am making you hear the voice of the Father as it declares me his true Son...”

After these dread words the offspring of Zechariah cried to the Creator, “I hesitate no longer, but do what you command me.” Having said this, he approached the Saviour as a slave his lord… The son of the priest in the office of a priest stretches out his palm and lays his hand on Christ.10

What a stupendous privilege! To Moses, at the burning bush, God reveals his sacred name, YHWH, that his people might forever praise and petition him by that name. But to John, at the Jordan, God reveals the triune substance of that ineffable name. To John it is given to learn at first hand of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit in the divine unity of being and act that the three-person’d God is. To John it is given to preside as the Jordan is parted – not with a rod, as when for Moses the sea was parted; nor yet with the ark of the covenant, as when for Joshua the river was parted; nor again with a cloak, as when the Jordan fled before Elijah and Elisha – but rather with the head of the Beloved Son himself, who thought it fitting thus to fulfill all righteousness.

Of David it is written that Samuel “took the horn of oil, and anointed him in the midst of his brothers, and the Spirit of the LORD came mightily upon him from that day forward.” Of David’s greater son, Jesus, it is written that John took the waters from below and anointed him in the midst of his brethren, while the Spirit was sent by the Father to anoint him with the waters from above. The Spirit, we are told, then drove Jesus deeper into the wilderness to take up his journey on the via crucis by wrestling with Israel’s great adversary – not a Philistine or a Samaritan, not an emperor in Rome or his forces in Palestine, not the Herodians or Pharisees or Sadducees, but the devil himself, who of all the biastai is the biastēs in chief.

No one presided, not even the centurion, when in that preternatural darkness at Golgotha Jesus underwent his baptism in blood. The devil, who there and then was utterly defeated by his own presumption, may have supposed that he was presiding, but the only president was that great high priest who “through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God.” In the Jordan, however, where Jesus’ journey to the cross began, John was given the privilege of presiding. That privilege had been reserved for him, as it had been reserved for Mary, by far greater privilege, to be the “ark” in which the Son of God first set foot in the waters below.

There could be no parting of the Jordan without the prior presence in Mary’s womb. As the source of Jesus’ humanity, Mary was and is greater than John. She sits at the right hand not the left. Yet neither John nor Mary did anything of themselves but consent. Neither essayed to seize anything by force. Mary consented to bear Jesus. John consented to baptize Jesus. Mary was rewarded by becoming the new Eve, mother of all the living. John was rewarded by the honour of presiding at the event through which the Son, as man and for man, publicly devoted himself to the Father and the Father responded by showing man the triune nature of God.11

Ravenna baptistry (Nicene not Arian)

John presides! He presides, and the Holy Trinity reveals himself to his people as their God and Saviour. He reveals Jesus as the Son. In the Latin rite, before the incensing of the offerings at solemn mass, an epiklēsis (to use the Greek term) is prayed by the priest, who makes the sign of the cross over the host and the chalice while invoking the Holy Spirit: “Come, O almighty and eternal God, the Sanctifier, and bless this Sacrifice, prepared for the glory of Thy holy Name.” This is what John the Baptizer does, though he does not at first realize that he is doing it. Down in the river Jordan, he stands already where Peter and James and John will stand on the holy mountain. He stands where every priest now stands before the altar of God. He prays the great epiklēsis and watches the divine response unfold. He has, in all humility, prepared the Sacrifice and is made witness to the triune Glory.

So why then does Jesus say that even the least in the kingdom is greater than John? He says it because everyone who receives the witness of the Son to the Father and of the Father to the Son, everyone who avails himself of the water and the blood, everyone who is irradiated in the resurrection by the Spirit of Glory, enters the kingdom and, by entering it, surpasses himself and every other mortal. John, too, will surpass John. Mary has already surpassed Mary. It is not the hand of John the Baptizer, nor yet the hand of Mary, but the right hand of Jesus the Christ which sees to that, as the author of the Apocalypse testifies. And when he does see to it, even the least on whom he lays his hand becomes greater than John then was, or of himself ever could be.

We will take up the third paragraph from Matthew 11 in the concluding part of this essay. More will have to be said there about the generation of John and Jesus, as about our own generation, in which, by reason of indeterminacy and averted gaze, almost everything has been left exposed to the biastai, to those who still seek to seize the kingdom by force. About falseness in Israel and falseness concerning Israel, about the place of Jerusalem in the prophetic scheme of things, about true and false authority, we must also speak further. But let us pause for now at something Romanos puts in the mouth of the Baptizer, to remind us of the surpassing grace of God that, working through consent, allows us to surpass ourselves:

I was feeble as a mortal, but he as God of all gave me force, crying, “Place your hand on me and I will give it strength.”12

The quoted texts are from Rev. 10:5–7 and Isaiah 47, respectively. With Daniel 9–12, compare Revelation 1 and 10–19, chapters replete with imagery drawn from Exodus, 1 Kings, Isaiah, Daniel, Malachi, and elsewhere.

Moses had already stood next to Jesus on Mount Sinai and at the door of the tabernacle; likewise at Meribah, where he sinned by a certain presumptuousness. Elijah had stood next to him in the cave at Horeb, while he was fleeing from Jezebel. John the Baptist had beheld him face to face by the Jordan, before being arrested by Herod. Elijah will stand next to him again, in a manner of speaking, by standing at the threshold of Jesus’ return in glory, before which Israel must be reconciled to its true patrimony (see Romans 9–11). Only then will the work of the law and the prophets be complete; only then will the city of God itself be complete and “all Israel” be prepared for the adventus in gloria; only then will the whole plan of salvation reach its goal.

Prophecy itself persists, of course, while the days of the biastai last, but it persists now within the ordo amoris expounded by Paul to the Corinthians and under the auspices of Jesus in his threefold office as prophet, priest, and king.

Enoch being, in both Testaments, more obscure than Elijah, a brief remark on him is in order. Cain called his firstborn Enoch, and named his city after him. But the generations of Cain are not counted in scripture, only the generations of Seth. The Enoch of Seth’s line, who fathered Methuselah, afterwards “walked with God” and “was not, for God took him.” We might say that he became a testament to the destiny of man had man not sinned, and a prophetic sign of what gratia elevans will accomplish in man in order to bring him to that destiny. Elijah likewise was such a testament, passing from the old creation to the new on the heavenly firecart. Yet they were both sons of Adam and, like Adam, must taste death after all. They who have witnessed in the court of heaven the unfolding of the secret plan of God, will again bear witness on earth, clothed like John in sackcloth. They will then be numbered with the martyrs, but will hear a second time the invitation, “Come up hither!”

See further my Ascension Theology, p. 52, and S. IV, 157ff. As for John (Yaḥyā) in the Qur’an, see C. 56, on S. III, 31–63, and S. VI, 83–90, with the notes there. See also S. XIX for a re-telling of the birth narratives of John and Jesus. For a learned response to Islam on the textual level, consult Gordon Nichols.

Islam, though an undeniably violent religion, is not without things of beauty or benefit, nor are all who practice it violent; a great many are not. But what Benedict XVI said in his notorious Regensburg lecture is more and more obviously true, both as regards Islam and as regards the patrimony of Secularism. See further the interview recently conducted by Diane Montagna and the remarks of Gavin Ashenden.

See John 1. The inclusion of John the Baptizer in the beginnings of all the Gospels forces us to take seriously that he comes with Jesus. He greets Jesus already from womb to womb, leaping for joy at Mary’s approach to his mother Elizabeth. Their lives and ministries mirror one another. John, who was the only son of a temple priest, belonged in the temple as a priest, but moved by the Spirit he decamped to the desert to prepare for a new temple and priesthood. Jesus was from the tribe of Judah, not of Levi, yet the old temple drew him like a magnet, for its fate was bound up with his. As a child, he chose to remain in the temple after a family visit there, instead of taking his place in the caravan returning to Nazareth. In his adult ministry he circled Jerusalem on its borderlands, after being anointed by God through John, as David did after he had been anointed through Samuel. Jesus then made his triumphal entry into the city and returned to the temple to confront its corrupted priesthood and to fulfill the prophecy of Malachi about its renewal.

This “first thing” is what is celebrated at the close of the Epiphany octave. I am of course aware that in the Novus Ordo Epiphany is no longer celebrated as an octave. That is a great loss, liturgically, one of many awaiting correction.

Matthew 28:16–20. See Acts 19, where those disciples of John whom Paul later found in Ephesus, “some twelve men in all,” are baptized into the triune Name, becoming a symbol of Israel itself passing into the new covenant prophesied by Jeremiah and ratified through the sacrifice of Jesus.

I am indebted to my Touchstone colleague, Jim Kushiner, for pointing me to Romanos, whose “poetic dialogue between the Reluctant Baptizer and the Saviour” can be found here.

With good reason, then, Luke constructs the opening chapter of his Gospel around the two of them, with a song of praise to each. What Mary and John contributed to our redemption – the human nature of the incarnate Son, in Mary’s case, the preparation and inauguration of his ministry in both cases – they contributed, not operatively, but cooperatively. With Jesus, things are different, as Romanos makes clear. Jesus contributes both operatively and cooperatively because he is the incarnate Son. Unlike Mary, who through him and because of him is full of grace, he is himself the source of that grace with which he is full and from which he fills others, beginning with her. Those who are keen on the title “co-redemptrix” for Mary do well not to forget this, and perhaps to revisit Joshua 3.

That is the logic of the life of faith lived here and now, as also of the purgatory through which we will pass in “crossing the Jordan” to that indescribably great theophany enjoyed by the blessed. See further my commentary on Thessalonians at pp. 131–36.

This is profoundly beautifull theology. The way you connect John's consent to baptize Jesus with Mary's consent to bear him really opened something up for me - I'd never thought about how both required humility and yielding to something bigger than themselvs. Your analysis of the preternatural aspect of the theophany at Jordan, where the Trinity is fully revealed, is something I'm gonna have to sit with for awhile. Really appreciate this deep dive into scripture and tradition.