St Stephen, Protomartyr

When John the Baptist pointed out Jesus to his disciples, identifying him as the Christ, two of them set off after him. Catching him up on the road, they dared to ask him:

“Rabbi” (which means Teacher), “where are you staying?” He said to them, “Come and see.” They came and saw where he was staying; and they stayed with him that day, for it was about the tenth hour.

Jesus did not stop over with them, but invited them to stop over with him. He made himself their host.

He wasn’t always quite so accommodating, however. On another occasion, “a scribe came up and said”:

“Teacher, I will follow you wherever you go.” And Jesus replied, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man has nowhere to lay his head.”

We may put down the difference between these two responses, not to the different situations of Jesus, but rather to the difference between one who does follow and one who merely promises to follow.

Another of the disciples said to him, “Lord, let me first go and bury my father.” But Jesus said to him, “Follow me, and leave the dead to bury their own dead.”

To promise is easy. To follow is difficult. It requires hard choices. But mark well: To follow Jesus is to follow one who came, as Irenaeus remarks, “not despising or evading any condition of man.” It is to follow one who knows what a man really is, and who is willing to show a man how to be a man.

Well, you say, that was then. Things are different now. Did he himself not say, “Where I am going you cannot come”? Yes he did. And where was he going when he said that? He was going to prepare a place for every man, woman, or child who chooses to follow. He was on his way to Golgotha to intercede for them. He was on his way, afterward, to the courts of his Father in heaven, that he might intercede for them there.

My little children, I am writing this to you so that you may not sin; but if any one does sin, we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous; and he is the expiation for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world.

Those who know this do not lose heart. Those who learn of it find a welcoming abode, even at the tenth hour. It is the Holy Spirit who sees to that. In the Spirit we still hear the invitation, “Come and see!” It is an invitation that now goes out to the whole world, and we ourselves remain here that we might help carry it to the world.

The Spirit and the Bride say, “Come.” And let him who hears say, “Come.” And let him who is thirsty come, let him who desires take the water of life without price.

We do not carry it in word only, but also in deed. “He who has my commandments and keeps them,” says Jesus, “he it is who loves me; and he who loves me will be loved by my Father, and I will love him and manifest myself to him.”

“Rabbi, where are you staying?”

On the road to Emmaus, there were two disciples who had no thought of catching up with Jesus. But the risen Jesus caught up with them. The Spirit did not at first permit them to recognize their Lord. But the hour being late, they invited him to stay with them and he obliged. He obliged, mind you, only as far as the blessing and breaking of bread, which he undertook, not they. They did not understand what they were offering or asking. They could not provide lodgings for him. He must provide lodgings for them.

There are those today who still don’t understand this. “Rabbi,” they ask, “won’t you stay with us? We’ll make a place for you. We can accommodate you. Would you like to see our plans? What liturgical delights we have in mind! What political and social panaceas! What a kingdom we will build for you!”

That was already Peter’s response, when he and James and John witnessed the transfiguration of Jesus. It was ill-considered then and it is still more ill-considered now. With that presumptuous invitation, the communio sanctorum they were enjoying on the mountaintop came to a sudden halt. Moses and Elijah departed, together with the Shekinah. Only Jesus was left. Peter was silenced by the Father in heaven, who commanded them to listen to Jesus, not to presume to instruct him; to be accommodated, not to accommodate.

Peter, being Peter, immediately forgot that lesson upon descent from the mountain. He did not learn it properly until his own encounter with the crucified and risen Lord. Even later, on that rooftop in Joppa, he struggled with it, but with the help of the Spirit finally mastered it. We forget it too, and have not at all mastered it, if we think we can cause Jesus to tarry with us in this present age, if we think to accommodate him with lodgings of our own design. That is a mistake that can only end in despair, for it can only begin in pride.

This is not to say (God forbid!) that there is nothing we can or should do. “Look carefully how you walk,” advises Paul; “not as unwise but as wise, making the most of the time, because the days are evil.” Jesus came, in evil times, to redeem the time. We, too, can redeem the time, if we are are looking for Jesus, preparing to be caught up by him on whatever road we are walking.

“Surely I am coming soon.” Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!

In that sense, we can and must make a time and a place for Jesus, for communion with him in the Spirit, that he may open our ears to his word and break bread with us. We must be diligent about that, even daring about that. Daring as Daniel and his friends were daring. Daring as St Boniface was daring, when he chopped down Thor’s sacred oak and hewed timbers for a chapel devoted to Jesus in the midst of pagan culture. And if there be some sacred oak, deep in the forest of our own wanderings, that needs the axe of Boniface, then we must fell it first. Christ himself will help us fell it, and hew it into serviceable timber. For Thor is no match for Christ, nor is any idol of ours.

We are authorized—nay, we are commanded—to overthrow idols, refusing the claims they make upon us and upon our time. Our time belongs to the Lord of time, and so does our every abode in the time we now have, the time that remains. And let us not take refuge in our doubts and uncertainties, as those Emmaus disciples might have, but did not. For even to the doubter commands have been issued.

To follow these commands is to struggle with doubt in such a way as to master it. The more we obey, the less we will doubt; the less we obey, the more we will doubt. Augustine said that we believe in order to understand and understand in order to believe. It can also be said that we believe in order to obey and obey in order to believe. Like the centurion whose faith Jesus praised, we are all men under authority. He who gives pride of place to doubt excuses himself from obedience to that authority. He should not doubt that he is a proud man, or that pride is the beginning of sin.

What ought we to doubt? We ought to doubt whatever kingdom, small or great, we think we are building for ourselves. The only true kingdom is the kingdom of God and his Christ, and it is not a kingdom we design but only a kingdom we declare. It is a kingdom incomparably glorious and quite beyond our comprehension. We pray for its coming, for its manifestation to us and to the whole world, yet we know it only as a treasure buried in the field between tribulation and patient endurance. We receive it only in a mystery, with reverence and awe.

“Rabbi, where are you staying?”

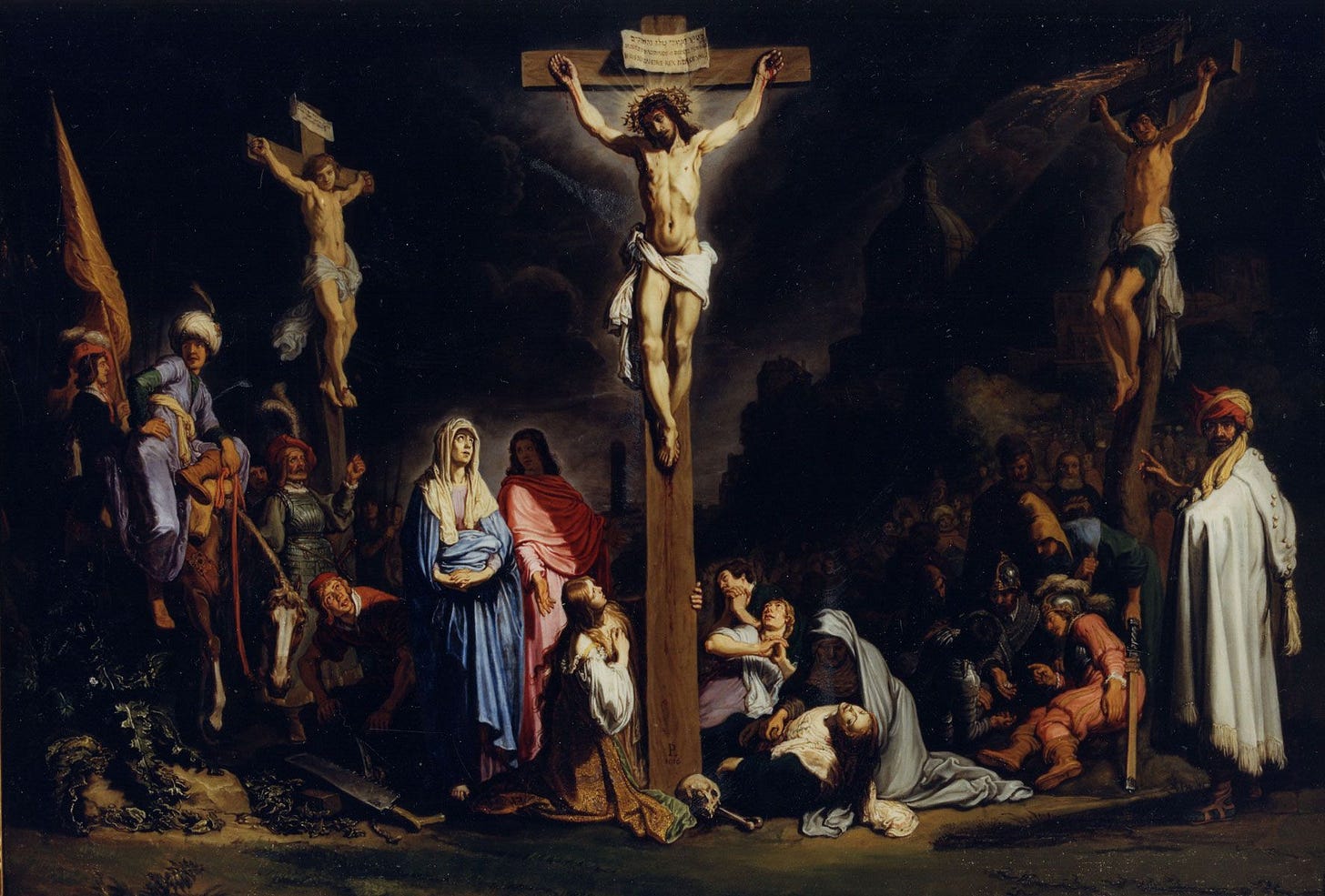

On his last night with us—I don’t mean the night on which the Eucharist was instituted, but that Night in the middle of the day on which it was preternaturally dark from the sixth to the ninth hour, the night in which he took authority over sin and death—Jesus lodged, not with two enquiring disciples, but with two hardened criminals.

One railed at him, demanding proof, by way of immediate deliverance, if he were really the Christ. The other recognized that proof was being provided—provided by Jesus’ very presence there, by his decision to situate himself between them, to hang on a cross he did not deserve. That one, in humble contrition, petitioned Jesus to remember him when he came into his kingdom. His request was granted, and granted promptly. “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

How could he know where Jesus was going, or how his kingdom would come? He did not know, and yet he believed. In his way, he became like the centurion. “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word . . .” He certainly was not worthy, but the Lord had entered under his roof, the dark roof of dereliction. The word was spoken with authority and his soul was healed. His body too, though broken, could rest in hope.

There was another man, soon after, who was also dying a criminal’s death. His name was Stephen. Very far from being a criminal, Stephen was a man of good works. Like Jesus’ own mother—she who had had been invited to provided accommodation for Jesus and who had done so, not presumptuously but obediently—Stephen was “full of grace and power,” full of the Holy Spirit. Yet he was being stoned to death for proclaiming Mary’s son as Lord.

Stephen was traveling with his Lord after the fact, much as St Simeon had traveled with him before the fact. At the end of his own road, he did not look down at the Christ-child to see his salvation. He looked up at the glorified Saviour. “Rabbi, where are you staying?” The heavens were opened to him. He saw the Son of Man, standing at the right hand of God. And his face shone with reflected glory, like the faces of Moses and Elijah. In the hour of trial, he was transfigured. He heard the glad invitation, “Come and see!”

The Church has always believed that this is the answer given to martyrs, though not all martyrs are like the protomartyr and few, perhaps, receive the answer before drawing their last breath. Jesus himself received it only after those three hours of darkness and vicarious dereliction.

My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?

Why art thou so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning?

O my God, I cry by day, but thou dost not answer;

and by night, but find no rest.Yet thou art holy,

enthroned on the praises of Israel.

In thee our fathers trusted;

they trusted, and thou didst deliver them.

To thee they cried, and were saved;

in thee they trusted, and were not disappointed.

Jesus had not earned darkness and dereliction, as we have, but he learned darkness and dereliction for our sake. He learned it with loud cries and tears, so that nothing of ours would be foreign to him or left unconquered by him. He learned it so that we might be forgiven, and nothing of which we repent be left unforgiven.

“Rabbi, where are you staying?”

The question is not a casual one. To ask it casually— especially at the Eucharist, where the answer “Come and see” is already heard by those who are looking for Jesus on the road—is to court great danger. It ought always to be asked in earnest, utmost earnest. It ought to be asked with the cross of Jesus in full view. It ought to be asked with our own cross in view. “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.”

What is the Eucharist, after all, but a disclosure of his abode? It is a disclosure of his dying and his rising, of his ascent to the Father, of his impending return in judgment. Thus are we situated alongside Jesus, privileged to share his abodes—all the abodes he took up for our sake. Paul draws the obvious conclusion:

If then you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth. For you have died, and your life is hid with Christ in God. When Christ who is our life appears, then you also will appear with him in glory.

So put to death what is earthly in you: immorality, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry. On account of these the wrath of God is coming. In these you once walked, when you lived in them. But now put them all away: anger, wrath, malice, slander, and foul talk from your mouth. Do not lie to one another, seeing that you have put off the old nature with its practices and have put on the new nature, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its Creator.

We are most inclined to ask the question in earnest, of course, when we are in difficulty ourselves, feeling forlorn and abandoned. Preparing his disciples for this, Jesus said to them: “A little while, and you will see me no more; again a little while, and you will see me.” He had in view the striking of the Shepherd and the scattering of the sheep. He had in view also his resurrection and his departure to the Father to receive his kingdom. But they did not understand.

Some of his disciples said to one another, “What is this that he says to us, ‘A little while, and you will not see me, and again a little while, and you will see me’; and, ‘because I go to the Father’? . . . We do not know what he means.”

They did not yet grasp that he must go for them, alone, to that place where the Father is hidden from view, to the place where the consequences of sin and faithlessness appear in stark relief. They did not understand that his kingdom was at hand, yet would remain hidden from view until a day known only to the Father.

The women who came to his tomb thought they knew where he was staying. Peter and John likewise, and doubting Thomas too. How surprised and delighted they were to discover that they were mistaken! But soon afterward he was on his way to the place where righteousness and faithfulness are rewarded, to the place where the Father is always evident, where his glory is in no wise obscured. And there they could not yet follow, save in a mystery.

The woman with the long infirmity, who had dared to touch the hem of Jesus’ garment, was healed. But Mary Magdalen, who had been healed of still greater infirmity—infirmity spiritual rather than physical—was warned: “Do not touch me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father; but go to my brethren and say to them, ‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.’” This he knew would produce sorrow not only for her, but for all who desire to follow him and to be where he is. Yet their sorrow would have meaning and purpose. It would be pierced by hope, not shame, the hope of his coming again in glory to receive them into the mansions being prepared for them in the presence of his Father.

Truly, truly, I say to you, you will weep and lament, but the world will rejoice; you will be sorrowful, but your sorrow will turn into joy. When a woman is in travail she has sorrow, because her hour has come; but when she is delivered of the child, she no longer remembers the anguish, for joy that a child is born into the world. So you have sorrow now, but I will see you again and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you.

Our faithfulness in his absence he employs in his preparations. Our recoveries from unfaithfulness too. Never forget that he does so! “God being wonderfully patient,” says Irenaeus,

man has learned both the good of obedience and the evil of disobedience, that the eye of the mind, instructed by experience of both, might choose judiciously the better things; that he may never be slack or neglectful of the command of God and, learning by experience how evil is that disobedience to God which deprives him of life, might never attempt such; and that, knowing how good is that which preserves his life, namely, obedience to God, he might guard it diligently, with all due care.

“Rabbi, where are you staying?” “Come and see!”

It is by means of the sacraments he leaves behind, like the cloak Elijah left to Elisha, that we may yet touch the hem of his garment and find grace to help in time of need. For though he has gone to the Father, he has not abandoned us, nor ever shall. He who took our side on Golgotha takes it still.

Let us then side with him and abide with him, that in due course we may also reside with him, not only in a mystery but in the full light of Day. For the Lord, as Paul says, “will rescue me from every evil and save me for his heavenly kingdom. To him be the glory for ever and ever. Amen.”

This wonderful reflection puts me in mind of a homily delivered by an Anglican bishop in Tasmania (Australia) in 1980, nearly 50 years ago. He was speaking on the ‘foxes have holes’ passage to illustrate what it means to follow Jesus. It is, he said, drawing from the gospel, 1) hard, not easy, 2) forward not backward, and 3) today, not tomorrow.

Thanks very much Douglas.

Thank you Douglas. A lovely and true meditation, beautifully expressed.