As Tocqueville famously foresaw, even without inkling of the technology on which it would rely, a new kind of tyranny is emerging with a reach far exceeding that of any forerunner. The tyrannies of old “weighed enormously on some, but did not extend over many.” That will change. “I do not doubt,” wrote Tocqueville, “that in centuries of enlightenment and equality like ours, sovereigns will come more easily to gather all public powers in their hands alone and to penetrate the sphere of private interest more habitually and more deeply than any of those in antiquity was ever able to do.”

This new brand of tyrant is building a new city, the silicon Nowa Huta. And it is doing so through the crisis it has manufactured. Given its technological prowess, its vast wealth and power will not prove subject to the moderating influence Tocqueville fancied. “The same equality that facilitates despotism tempers it,” he argued, such that men will be subject rather to schoolmasters than to despots of the more capricious type. That rings true in the West, perhaps, where the globalist state of Davos design will be very much the nanny state. But little comfort can be drawn from it, even by those who are not distraught at the reversion of “enlightened” man to his once-despised adolescence. For what is going on in the West, as in the East, is plainly as callous as it is calculated.

I re-present this passage from The Emerging Nowa Huta, written in the summer of 2021, because I want to remind readers of an uncomfortable fact; namely, that we are in no position to look back on our troubles, as if they were behind us and our only task were to learn how to prevent them from recurring. That is the posture of our opponents, of the wealthy and powerful who are busy preparing to multiply our troubles. Today we hear many saying, “Mistakes were made; we'll do better next time.” Unfortunately, they really mean it. We hear many more saying nothing at all, because they do not want to face their own complicity in those mistakes, which were not really mistakes but rather crimes imperfectly carried out.

Were we ourselves truly in a position, the enviable position, of learning at leisure how to do better next time, the war would be over and the victory won. But that is not the case. Justice has yet not been served. And without justice there can be neither mercy nor hope, only a bitter expectation of more of the same. Of this Vera Sharav, for example, is right to warn us. Those who dismiss such warnings, pointing out (as is easy enough) their journalistic flaws, are overlooking persistent patterns and root causes, causes identified by those who could see our troubles coming even before they arrived.

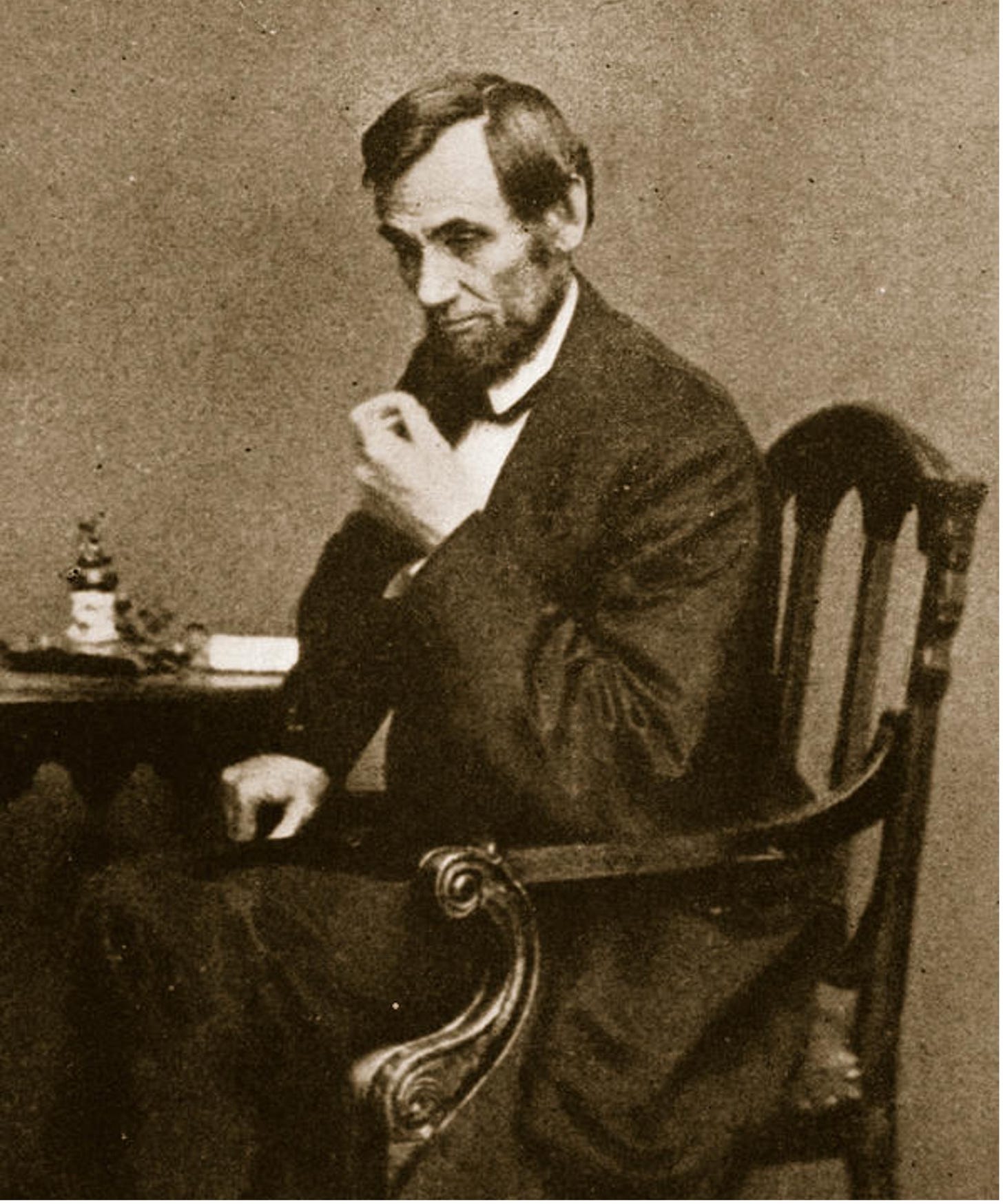

Take Abraham Lincoln, for example. It was but twenty-one years after the publication of the second volume of Democracy in America, which appeared in 1840, that the Civil War broke out. When that war was nearing its conclusion, Lincoln wrote to Col. William Elkins as follows, in a letter dated 21 November 1864.

We may congratulate ourselves that this cruel war is nearing its end. It has cost a vast amount of treasure and blood... It has indeed been a trying hour for the Republic; but I see in the near future a crisis approaching that unnerves me and causes me to tremble for the safety of my country. As a result of the war, corporations have been enthroned and an era of corruption in high places will follow, and the money power of the country will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the people until all wealth is aggregated in a few hands and the Republic is destroyed. I feel at this moment more anxiety for the safety of my country than ever before, even in the midst of war. God grant that my suspicions may prove groundless.

Alas, they were far from groundless, though attempts to excise this passage from Lincoln's literary corpus are groundless. War, as that great man understood, creates a new normal, a military-civilian fusion, which advances both corporate and bureaucratic agendas. Those who benefit from that advance, financially and politically, wish to extend the conditions under which they benefit. They have new wealth and new networks through which to do so. Corruption does indeed follow, even to the extent of conspiracy to produce further war.

As Ted Nace observes in Gangs of America, Henry Adams made remarks along the same lines as Lincoln’s, articulating again a deep concern that the American political system was not well equipped to prevent the conditions under which large corporations, “after having created a system of quiet but irresistible corruption,” would “ultimately succeed at directing government itself.” Here, from Chapters of Erie, which the Adams brothers published after the Black Friday crisis of 1869, is a fuller excerpt:

For the first time since the creation of these enormous corporate bodies, one of them has shown its power for mischief, and has proved itself able to override and trample on law, custom, decency, and every restraint known to society, without scruple, and as yet without check. The belief is common in America that the day is at hand when corporations far greater than the Erie swaying power such as has never in the world s history been trusted in the hands of mere private citizens, controlled by single men like Vanderbilt, or by combinations of men like Fisk, Gould, and Lane, after having created a system of quiet but irresistible corruption will ultimately succeed in directing government itself. Under the American form of society, there is now no authority capable of effective resistance.

Subsequent history has shown that such concerns were more than justified, though just how far the whole business might go, and in what direction, is only now becoming apparent.

A century after the Civil War, a more familiar text—the farewell address of President Dwight Eisenhower in 1961—returns to the same point. “To foster progress in human achievement, and to enhance liberty, dignity and integrity among people and among nations,” declares Eisenhower, are the proper goals “of a free and religious people,” goals built into “America's adventure in free government.” But these goals are threatened by the Cold War conflict—threatened not only by “a hostile ideology global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method,” but threatened also by the ability of that conflict to upset the “balance in and among national programs; balance between the private and the public economy, balance between cost and hoped for advantage, balance between the clearly necessary and the comfortably desirable, balance between our essential requirements as a nation and the duties imposed by the nation upon the individual, balance between action of the moment and the national welfare of the future.”

Has not the whole effect, if not the whole design, of our recent troubles been to disturb or even to overturn what remains of these balances? At all events, we see happening the very things that worried him, including “the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.” Here especially, he warns, there is real “potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power,” power that only “an alert and knowledgeable citizenry” can hope to overcome. This potential is magnified by a related feature. “Akin to, and largely responsible for, the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture has been the technological revolution,” a revolution capable of adversely affecting the vital institutions of free societies, institutions such as the universities.

In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the federal government. Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers. The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded. Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

We have a handy label for the latter phenomenon, lent to us by the elite's propaganda machine, formerly the free press. There it is called “following the Science.” Elsewhere it is called regulatory capture. In Canada, it is called Rouleau, though that term is strictly political, being a (lightly corrupted) contraction of “Rule of Trudeau.”

Now, what lies at this intersection where the interests of the military, the scientific-technological elite, big business, and big government converge? In a word, medicine, if by that word we mean something capacious enough to accommodate deliberate harms—which we have meant ever since we took up eugenic practices and “medical” abortion. Eisenhower doesn’t mention medicine. But where, more obviously than there, shall we look for a melding of motives and measures likely of success on a national or even global scale? Is it not precisely in medicine and health (another much abused word, especially when qualified by adjectives of scale) that the unhappy prospect of domination “by federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money” is realized?

Medicine now means all sorts of things in which both business and government have vested interests, even the dispatching of the elderly or the down on their luck, since these are useless consumers of tax dollars. But above all it means pursuit of the holy grail of eugenics. The computerization of medicine has given eugenics a new lease on life, and a licence to take new liberties with life. It has also created instruments of observation and control that deprive life of liberty.

Eisenhower, being a military man, would doubtless recognize the diversionary tactics being employed here. While all eyes are on the beach where reason itself is being reduced to ashes by a pair of fire-breathing monsters, one scorching even the most elementary truths of human nature and the other threatening the ruin of all nature, the real landing is being made elsewhere. Medical science is constructing its own chimera. Man, no longer a body-soul fusion, is being reinvented as a bio-digital fusion. His final end will not be happiness in God but a place in the databanks of global governance.

Those who suppose that scientia est potentia—not knowing that, absent love, both knowledge and power are mere illusions—are busy building their new bio-economy in which the citizenry, no longer alert and knowledgeable, will be composed of serfs living under the watchful eye of technocrats and in subjection to what the latter refer to as “agile rule-making.” Which does indeed mean the end of democracy and of the American republic, as I suggested in America’s War. In feudal terms, monetary, monitorial, and managerial prepollence will render bellatores alert and knowledgeable, hence able to act pre-emptively, while laboratores will find themselves totally reliant and without benefit—for their situation will not be mediaeval but quintessentially modern—of mediation from oratores.

This emerging capacity for unrestricted surveillance and control of the populace, this panopticon effect, is what distinguishes what is happening today from its nearest prototype, the cruelly coercive anthrax vaccination campaign that accompanied the Gulf War. Its international reach, and its totalitarian potential, seem to be a matter of concern even to the pioneering cyborg enthusiast, Elon Musk, whose Neuralink project, at first glance, appears to be all of a piece with it. Whether he acts on this concern, we shall see. His design is as yet incomplete, and more than a little problematic. Perhaps he will reconsider?

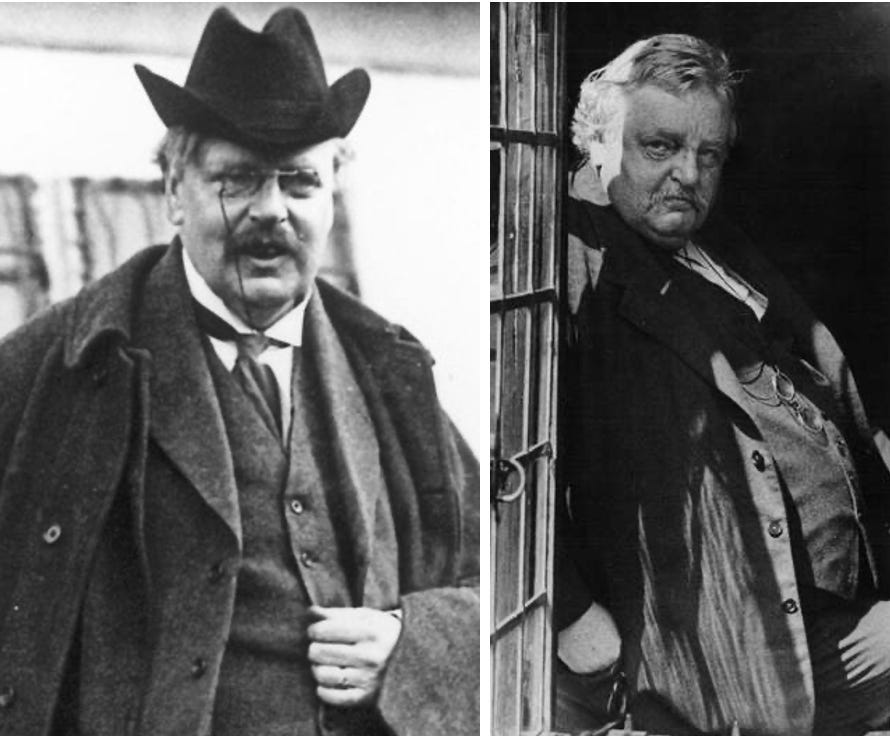

In Anarchy from Above we saw how G. K. Chesterton predicted the rise of the eugenic health tyranny that is the main instrument of the wealthy and the main arm of the pincers by which so much that is precious to us is being plucked from our midst. The existence of the Wellcome Trust, of the GPMB, of GAVI and CEPI and DARPA and BARDA and SAGE and all the other acronymic partners to the lewd dance of public-private couplings (conducted these days from the World Health Organization by its new scientific director, Sir Jeremy Farrar) would not have surprised him in the least. But neither would that other lewdness, lewdness of the more literal kind, which constitutes the pincers' second arm. Here's another famous quotation, too often appealed to, perhaps, but not often enough in this very connection:

For the next great heresy is going to be simply an attack on morality; and especially on sexual morality. And it is coming, not from a few Socialists surviving from the Fabian Society, but from the living exultant energy of the rich resolved to enjoy themselves at last, with neither Popery nor Puritanism nor Socialism to hold them back. The thin theory of Collectivism never had any real roots in human nature; but the roots of the new heresy, God knows, are as deep as nature itself, whose flower is the lust of the flesh and the lust of the eye and the pride of life. I say that the man who cannot see this cannot see the signs of the times; cannot see the sky signs in the street that are the new sort of signs in heaven. The madness of to-morrow is not in Moscow but much more in Manhattan... (G.K.'s Weekly, 19 June 1926).

Chesterton recognized the moral causes of the West's decline, and their consequences, with a clarity few others achieved at the time. He recognized the heavy hand of the stakeholder capitalists who were trying to recreate us in their own image, or rather to render us pliable to their own purposes, which is what they mean when speaking of an “open” society. Were he himself drafting for Eisenhower that farewell address, he would not, I am confident, have brought it to a close quite like this:

You and I—my fellow citizens—need to be strong in our faith that all nations, under God, will reach the goal of peace with justice. May we be ever unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power, diligent in pursuit of the Nation's great goals. To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing inspiration: We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations, may have their great human needs satisfied; that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full; that all who yearn for freedom may experience its spiritual blessings; that those who have freedom will understand, also, its heavy responsibilities; that all who are insensitive to the needs of others will learn charity; that the scourges of poverty, disease and ignorance will be made to disappear from the earth, and that, in the goodness of time, all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

Why not? Well, because this reads rather like J. S. Mill at prayer. And J. S. Mill, quite sensibly, did not pray, save to the god Comte had constructed, the god whose day has come and gone. Mill believed that the “vicissitudes of fortune, and other disappointments connected with worldly circumstances,” were “principally the effect either of gross imprudence, of ill-regulated desires, or of bad or imperfect social institutions.” He also thought all this could be fixed, that such ills were “conquerable by human care and effort.” That's what people tend to think when they don't think very hard about original sin, something Mill was quite sure we should not think about. But not thinking about it leaves us prey to those who use our optimism and good will against us; prey to those who believe that the differences between men are faults of nature rather than moral faults; prey to those who, abandoning all morality, have embarked so enthusiastically on the path of changing nature. It leaves us, as Sharav says, to the fascists, to those drunk on money and power. It leaves us to the fixers, the universal comptrollers, the ziggurat men, to the Bank for International Settlements and other coercive or subversive instruments of a misanthropic international order.

When remarking on H. G. Wells' A Modern Utopia, which extends Mill's vision, Chesterton observed that Wells had made “disbelief in original sin” one of its primary features. To which he retorted that had Wells only “begun with the human soul”—had he dared to set out with an act of self-examination—“he would have found original sin almost the first thing to be believed in.” For he would have discovered “that a permanent possibility of selfishness arises from the mere fact of having a self, and not from any accidents of education or ill-treatment.” (Note that the almost and the “possibility of” are indispensable here, if we are not to join the amoralists.) That being the case, however, we cannot reasonably expect that “all peoples will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.” Those who promise such a thing either lay claim to a supernatural power to achieve it or they promise what they cannot deliver. Absent the God-man, both horns of that dilemma are deadly; hence we must be diligent to escape it. “So, if they say to you, ‘Lo, he is in the wilderness,’ do not go out; if they say, ‘Lo, he is in the inner rooms,’ do not believe it.”

Eisenhower was not a philosopher, of course, nor Chesterton a military man. The story is told of the latter that, at a dinner party during the Great War, his hostess asked him why he was not out at the front. His explanation was offered with self-deprecating humour: "Madam, if you step round to the side you will see that I am out at the front." Chesterton's physical girth was more than matched, however, by a theological girth that positioned him to see what neither Mill nor Eisenhower could see; namely, that the myth of progress was just that—a myth, and a quite toxic one, albeit a resilient one.

To put the matter in my own terms, it is not in the goodness of time (though time, like everything else God makes, is good) but in the fullness of time that all people “will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.” And the fullness of time is not something that we, collectively and by our own herculean efforts, are on the way towards, but rather something that by divine determination is on its way towards us, something that will arrive both as judgment and as mercy.

Or, to put it in Eric Voegelin's terms, progress has its price, and that price is “the death of the spirit.” German idealism supposed it to be the advance of Spirit, but it is not so.

The more fervently all human energies are thrown into the great enterprise of salvation through world–immanent action, the farther the human beings who engage in this enterprise move away from the life of the spirit. And since the life of the spirit is the source of order in man and society, the very success of a Gnostic civilization is the cause of its decline. A civilization can, indeed, advance and decline at the same time—but not forever. There is a limit toward which this ambiguous process moves.

This limit, adds Voegelin, “is reached when an activist sect,” a sect that has secretly “sacrificed God to civilization,” subsequently “organizes the civilization into an empire under its rule. Totalitarianism, defined as the existential rule of Gnostic activists, is the end form of progressive civilization” (A New Science of Politics, 131).

Eisenhower rightly suggests that faith is not fruitless, nor prayer unproductive, and that peace with justice is no mere pipe dream. We are but dreaming, however, if we suppose the march of time to be, by some friendly providence—Annuit coeptis!—a march to inevitable victory. What we require here is not a booster dose of Romantic optimism, but rather a bracing shot of vintage realism.

That is what Augustine supplies when, in book five of The City of God, drawing on The Cataline Conspiracy, he quotes Cato the Younger. “Do not imagine,” says Cato,

that it was by force of arms that our ancestors made the republic great from its small beginnings. If that were true, we would have a far more excellent republic now than they did then. Indeed, we are far better supplied with allies and citizens, and with arms and horses, than they were. But it was other qualities that made them great, qualities which are wholly lacking in us: diligence at home, just rule abroad, and an independent spirit in counsel, addicted neither to crime nor to lust. Instead of these, what we have is self-indulgence and greed, public impoverishment and private wealth. We praise riches, we live for idleness, we make no distinction between good people and bad, and raw ambition usurps all the rewards that virtue ought to have. And it is no wonder—when each of you takes thought only for himself, when you are slaves to pleasure at home and to money and favor here in public—that any assault would come on a republic that has no defenses.

“When morals have been corrupted,” repeats Augustine, “we find public impoverishment and private wealth.” Lincoln couldn't have said it better. The corruption of morals, the enrichment of base but mighty men, the decay and collapse of the republic: Are these not the very maladies he diagnosed? Does the first of these maladies, combined with the opportunities created by war—including phoney wars, like the viral war on terror or the terrorist war on viruses—not breed the flagitious oligarchy that troubled his dreams and now troubles our days? If so, we cannot get to the root of the problem without moral examination, the very thing so many are so very keen to avoid. Even Cato, at the last, who in pride preferred suicide to martyrdom.

At the outset of Lent, we should not need reminding that examination of conscience and the fight against crime are not mutually exclusive enterprises. Rightly conducted, they are mutually reinforcing. I will say more of that anon, making further appeal to The City of God, and more also of the distorted view of providence that misdirected Peter, misdirected America's founding fathers, and still misdirects today. In conclusion, however, I want to restate my present concern, which in the last analysis is quite a simple one.

What was foreseen more than a century and a half ago, while the Civil War still raged, what has evolved in our midst in the intervening era and come to fruition in the great covid fraud—a fraud that has introduced a new kind of civil war into country after country—is not going to disappear with the last traces of inflammation it is capable of producing. One cruel war, or tactic of war, gives way to another. The limit has not been reached. The end is not yet.

Realism is not pessimism, however, which is no healthier a response than optimism. Despair is not the antidote to false hopes, but rather their final fruit. What is required is faith. Faith and prayer. Faith and prayer and perseverance, for true hopes are the only antidote to false.

Last Sunday, in the old missal that a certain prickly pope impugns, was Sexagesima Sunday. I will leave those who do pray—for we must all, in our station, be intercessors and oratores now—with a few extracts, drawn mainly from the Psalms, that may serve as a model.

Introit (Ps. 17): ARISE, why sleepest Thou, O lord? arise, and cast us not off to the end. Why turnest Thou Thy face away, and forgettest our trouble? our belly hath cleaved to the earth: arise, O Lord, help us and deliver us.

Collect: O GOD, who seest that we put not our trust in any thing that we do: mercifully grant that, by the protection of the Doctor of the Gentiles, we may be defended against all adversities.

Gradual (Ps. 82): LET the Gentiles know that God is Thy Name: Thou alone art the Most High over all the earth. O my God, make them like a wheel [i.e., tumbleweed] and as stubble before the wind.

Tract (Ps. 59): THOU hast moved the earth, O Lord, and hast troubled it. Heal Thou the breaches thereof, for it has been moved. That they may flee before the bow: that Thine elect may be delivered.

Offertory (Ps. 16): PERFECT Thou my goings in Thy paths, that my footsteps be not moved: incline Thine ear, and hear my words: show forth Thy wonderful mercies, Thou who savest them that trust in Thee.

As for those already inclined to pray, but not otherwise to resist, let them take to heart the rebuke of their passivity found in the opening verses of the epistle reading from the said doctor, without which that anti-Pelagian collect, and Paul's paean to the power of weakness, may be horribly misunderstood.

“You suffer it,” he says, his words dripping with sarcasm, “if a man bring you into bondage, if a man devour you, if a man take from you, if a man be lifted up, if a man strike you on the face. You bear gladly with fools, being so wise yourselves! For you bear it if a man makes slaves of you, or preys upon you, or takes advantage of you, or puts on airs, or strikes you in the face.”

Such, too, is false hope, not true. The way of true hope he goes on to explain. It is, of course, the way of Christ. Not public impoverishment and private wealth, but personal impoverishment and public wealth.

After coming back to this and reading it again, this thought: your prescription at the end is apt. Recently the Public Order Emergency Commission (predictably?) found the government's invocation of the Emergency Measures Act was justified. If I thought our hope was in government or the courts, this would be a time to despair. Canada is notably and measurably declining at a precipitous rate. But since I know our hope is in the one who rules over governments, and who tells us "Do not put your trust in princes", I don't despair. At the same time, as you rightly point out, we should be prepared to both pray *and* act.

Excellent, Doug, and a helpful reminder to those of us who psyches wander too frequently false hope or despair.